Architect A. Quincy Jones - Page 4

Eichler Homes commissioned the firm's core work in the north. Beginning in the early 1950s and continuing for more than a decade, Jones and Emmons produced dynamic, livable housing for the postwar moderate-income family at Joseph Eichler's request. They also were intent on creating quality community planning, a concept their firm exhibited from its first collaboration with Eichler, the 1952 Ladera Project in Portola Valley. Twice featured in Arts & Architecture magazine, the development's plan called for seven different single-family designs on a hillside setting that featured pairs of mirrored plans, shared driveways, and high density with a feeling of spaciousness. While Jones and Emmons' Ladera Project was never fully completed, the ideas they introduced there—in particular the concept of shared landscapes—carried over to future projects. Two years later, their designs for the Greenmeadow development in Palo Alto included a community center with a nursery school and a swimming pool. The development was typical of the thoughtful arrangement of one house to another carried through to the thoughtful arrangement of house to community, a philosophy that remained constant in the housing proposal produced by the firm of Jones and Emmons.

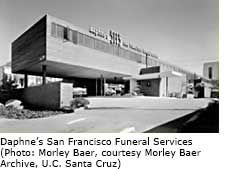

Jones and Emmons' first commission in Northern California was with the mortician Nicholas Daphne. In 1949, Daphne commissioned Jones to design a mortuary in San Francisco at Market and Duboce Streets. As a great supporter of modern architecture, Daphne contacted Frank Lloyd Wright after the war, and asked him to design his mortuary, but inevitably severed relations with Wright. In 1948, while returning by car from Arizona, Daphne drove through Palm Springs and stopped at the Town and Country Restaurant, which had been designed as a joint venture by Paul R. Williams and A. Quincy Jones. Daphne was so impressed by the qualities of the architecture that he sought out the rstaurant's architects, and ultimately commissioned Jones to design a building for his San Francisco Funeral Services.

At the request of Daphne, Jones and Emmons worked with a consulting architectural firm in New York, Petroff and Clarkson, who had experience in mortuary design. The organization of the design provided for three basic functions: the conducting of the funeral arrangements, the preparation of the deceased for burial, and the conducting of the funeral ceremony. Concealed ramps transported the deceased to a second-story viewing room. Sitting rooms were integrated with the landscape, resulting in areas conducive for quiet contemplation. Jones and Emmons' design leveled out the sloping site. Parking was designed underneath the structure and the building was situated to one side of the site, leaving room for a future chapel. The chapel was never built, leaving park-like surroundings for the buildings that were constructed. To draw attention away from the unattractive surroundings, the building's focus was inward, on to landscaped courtyards.

The Daphne contained many of the modern elements characteristic of postwar architecture. Large expanses of glass and interlocking of horizontal and vertical planes connected indoor and outdoor space. The ground plane was freed up for vehicular movement. The flat-roofed building of redwood and brick appeared to float above a porte-cochere. A simple rectilinear structure with ribbon windows integrated with a series of courtyards created a commercial structure very much in human scale. Jones designed his own Southern California home the same time as this project; both showed the same transparency and form.

In 2000, preservation groups rallied in an unsuccessful attempt to save the Daphne when threatened with demolition to make way for low-income housing. Inevitably razed, Daphne's San Francisco Funeral Services was a sad loss, not only as one of a handful of postwar modern commercial structures in the city of San Francisco, but as perhaps the most interesting commercial project designed by Jones and Emmons in Northern California.

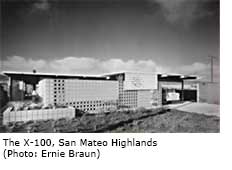

In the mid-1950s, Eichler commissioned architect Raphael Soriano to design a steel prototype, in Palo Alto, the first steel house in the country for a merchant builder. It was completed in 1955; and a year later, Jones and Emmons finished another steel house for Eichler in San Mateo, the X-100. Jones had finished construction on his own steel house for his family in 1954. It was designed with precision and efficiency in order to have all of the steel for the house delivered at one time on one truck and erected in one week. In actuality its rigid steel frame was completed in three months. The X-100 was the firm's first steel house project for mass production. Steel demanded a precision unlike wood construction, which could tolerate variances in details of one half of an inch. The ease and speed of steel construction promised great savings in labor. Houses could be designed as an open box with the few non-structural walls finished in standard panels of gypsum board easily applied to a steel grid.