Arts & Architecture: Magazine with a Mission - Page 2

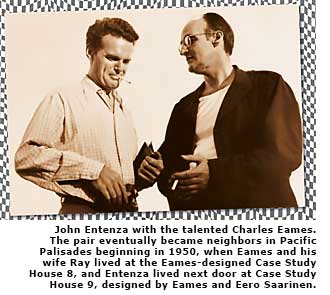

"'Arts & Architecture,'" he wrote in the introduction to a recent reprint of the magazine by Taschen, "was at the leading edge in architecture, art, music—even in the larger issues of segregation in housing and education and other manifestations of racial bias before they became codified as civil rights. The magazine was hopeful about life; it had a sense of mission. John Entenza's moral seriousness—leavened by his wry humor—infused the magazine."

Entenza was not the first editor of the magazine to adopt an activist stance. Back in 1932, during the worst months of the Depression, editor Harris C. Allen vowed to devise strategies for providing people with affordable homes.

"President Hoover's astute selection of the modern American home on which to focus the attention of the country just now shows a deeper knowledge of our economic problems than does any other move yet made to solve them," Allen wrote. "To show these houses and to set forth the American spirit which illuminates them will be the object of every coming issue."

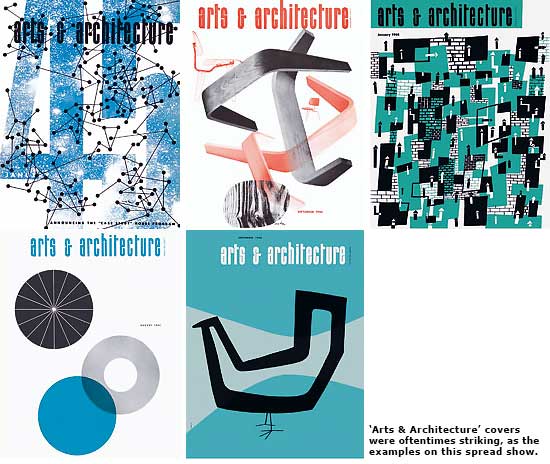

'Arts & Architecture,' in other words, is a much more compelling magazine, and a more surprising one, than fans who know only its Case Study houses might imagine. Although the magazine is known today for its advocacy of modernism, and for an emphasis on architecture, it began with a focus largely on traditional architecture—and never lost its interest in music, crafts, furnishings, paintings, sculpture, and social issues.

In fact, much of the finest writing in 'Arts & Architecture' is about music, (thanks to Peter Yates, a brilliant critic whose focus, not surprisingly, was on musical modernism) and art—but not architecture. That was intentional. It was Entenza's policy—one continued by Travers—to let the architecture speak for itself with little commentary and no criticism. "We had a policy of not criticizing architecture," Travers said in a recent interview, "just not showing what we didn't like."

From its beginning in 1929, 'California Arts & Architecture' was a high-toned, arts magazine aimed at well-heeled intellectuals—not a to-the-trade building publication (like 'Progressive Architecture'), nor a popular home-and-living magazine (like 'House Beautiful' or 'Sunset'). It was closer in tone to a literary magazine.

The magazine reached beyond design into society. Entenza ran editorial after editorial extolling UNESCO for breaking down racial and cultural stereotypes. "No true culture," he wrote, "is the enemy of others." One long essay, which ran over several issues, was 'An Experiment in Correlation: The Psychological Impact of Atomic Science on Modern Art,' by a Spanish psychiatrist.

Also from the start, the magazine's cast was impressive. Mark Daniels, the editor for much of the 1930s, was a well-known landscape architect who laid out Sea Cliff in San Francisco and helped plan national parks. On the advisory board were Arthur Brown Jr., one of San Francisco's leading architects (City Hall), architect Irving Morrow (the Golden Gate Bridge) and Thomas Church, one of the fathers of modern landscape design.

Leafing through early issues makes clear how modernism ever so gradually made inroads into the American consciousness—even in so progressive a clime as Southern California.

Tudor houses and Spanish Colonials mix easily in early issues with ranch-style houses "with real Californian-colonial characteristic." Modernism makes its appearance with baby steps.

"If I had a house to design at Pebble Beach, what would I do?" Morrow mused in 1932. "...Surely to inject the mechanistic angularities and suppression of a Gropius or Le Corbusier would do violence to the very principle with which I opened the discussion, that buildings should be integrated with the land...Is it fantastic to consider Pebble Beach as a destined laboratory for the humanization of modern architecture?"

In 1937, a year before Entenza, the magazine was focusing on small, unpretentious ranch-like homes 'in the California manner.' Later that year, Palm Springs' now-famous streamlined 'Ship of the Desert' home sailed through one issue of the magazine—which emphasized its love for Art Deco by reproducing 'Three sets from the picture Shall We Dance,' a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers romp.

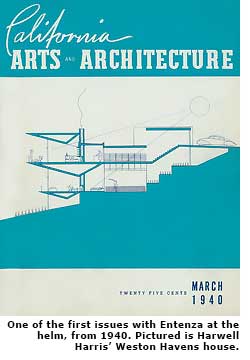

Entenza, who bought the magazine in 1938 after it went through bankruptcy, gradually upped its modernist quotient with articles on sleek interior designers Paul Frankl and Kem Weber, pieces on Swedish Modern, 'plants for modern gardens,' and 'Modern design matures' by Richard Neutra.