Beyond Flash and Fantasy - Page 2

The Chemosphere is a delight, said Lauren Taschen, who lives there with her husband Benedikt. "It feels like being a little kid up here, living in a big tree," she said. The house, on what Lautner had called an "impossibly" steep slope, is reached by a funicular. Though it's a structural wonder, an octagonal pod held up by a basket of steel beams resting on a reinforced concrete pier, the effect inside is warm, thanks to a stone wall and built-in seating around the fireplace.

The house, with an open living area and a bedroom tucked into one corner, is only 2,200 square feet. When Frank Escher, the architect who renovated the house for the Taschens, took the late filmmaker Billy Wilder and his wife Audrey on a tour, he recalls, "She looked up at the house and said, 'This is a cottage!' "

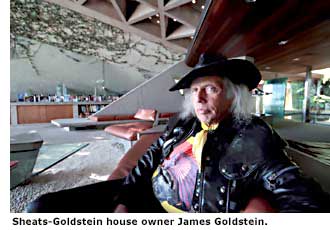

James Goldstein, one of Lautner's best and longest-lasting clients, demolishes another Lautner legend: "He had no ego problem whatsoever."

"He was very rebellious, against the ways of society, against the restrictions that were placed upon him by building rules, by financial institutions that wouldn't make loans on things he had designed because they weren't understandable to the lender," Goldstein said.

But when it came to the project at hand, Goldstein's 30-plus-year effort to "continue creating" the Sheats-Goldstein house, "Lautner would always defer to me. Every new project has been my suggestion. He never said, 'Jim, I think we should do this. What about doing that?' He never said that kind of thing."

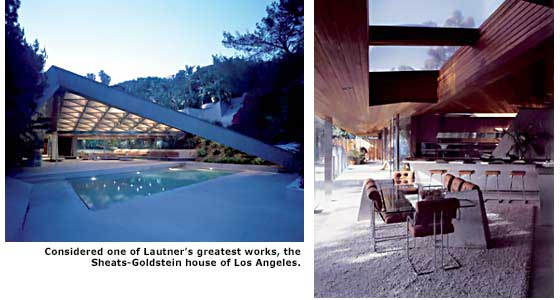

The Sheats-Goldstein house, originally designed in 1963 for Helen and Paul Sheats, is one of Lautner's great works. A dramatically folded roof of coffered concrete shelters glass-walled, woodsy rooms. Living there, Olsberg writes, is "like living in the folds of origami, with a carefully framed prospect that stretched forever."

Goldstein, a fan of Frank Lloyd Wright since childhood, was knocked out by the home when he first saw it—despite some injudicious changes. Each coffer in the coffered ceiling, for example, had been painted a different color.

"I love the clean lines, the inside-outside continuity, the way everything blends in with nature, the use of natural elements, the ability to enhance the view," Goldstein said. "Many people have said to me that I was his perfect client. Budgetary considerations were never a factor. It was, 'How can it be done to achieve the utmost perfection?'"

Lautner grew up on Lake Superior, in the forests of upper Michigan, in what he described to Valentine as a "philosophical nature environment." His mother Vida designed an Arts and Crafts log cabin above the lake. Lautner, who was 12, and his father, John, a professor who had studied in Heidelberg and Paris, built it by hand, felling the trees and using winches and windlasses to move logs uphill.

Lautner valued craftsmanship highly—its lack was another reason he came to despise modern America—and often worked with expert builders like John de la Vauz or Wally Niewiadowski. "Good client, good architect, and good builder," he told Laskey. "That's all you need. But that very seldom happens."

Lautner married young and well to a woman whose "grandfather owned half of northern Michigan," he told Valentine. Soon John and Marybud Lautner were living with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesen in Wisconsin. During his apprenticeship Lautner did everything, with a particular emphasis on steamfitting. He stayed with Wright for 11 years, working with him on his plan for the prototype Broadacre City, and on prototypes for what Wright called "the modest house."

It was Wright who dispatched Lautner to Los Angeles, where they worked together on several homes. By the early 1940s Lautner was working on his own, though he would continue to partner with Wright when the master called. And when Wright visited town, Lautner would always happily chauffeur him around.

After World War II, Lautner joined the firm of Doug Honnold, a successful and eclectic architect who got involved in the Mutual Housing Association's plans for cooperative housing in Crestwood Hills in the Los Angeles hills. Lautner originally worked on that project, which also involved architect A. Quincy Jones. But in 1947 Lautner departed the project, and the firm, when he took up with Honnold's wife, Elizabeth, whom he married after divorcing Marybud.

What followed was what Olsberg characterizes as the first of several boom periods for Lautner—all were followed by busts. By 1951, Olsberg said, Lautner was almost broke.