Distinguished at Every Curve

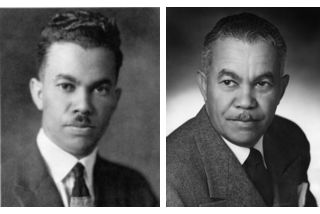

On its face, the story of Paul R. Williams may seem simple. Extraordinary, for certain—even the stuff of legend. But comprehensible.

|

|

|

A black boy, orphaned young and raised poor, proves both talented and ambitious. I want to become an architect, he tells his teacher.

“Whoever heard of a Negro boy being an architect?” was the answer. Circa 1910, the answer was: “Nobody.”

By age 20, Williams (1894-1980) was working for a leading Los Angeles architect, and was soon designing houses on the side for building contractors. By 26, he was a licensed architect and by 27 had his own highly successful firm.

Five years later, not only was Williams one of the two or three leading black architects in the country, he was one of the foremost residential architects of any sort in Southern California, a man the New York Times would later dub ‘architect to the stars.'

|

|

|

Clients included Lon Chaney, Zasu Pitts, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Bert Lahr, Tyrone Power, Johnny Weissmuller, Frank Sinatra, and Charles Correll, the white actor who voiced Andy in the radio series Amos and Andy. One early client was an imperious auto magnate for whom Williams designed a 32,000-square-foot Beverly Hills estate.

Williams became the first African-American to join the American Institute of Architects and the first to be named an AIA Fellow. He served on Los Angeles' planning commission, and state and federal bodies. He opened an office in Colombia. His firm, which grew to several dozen people, had completed about 3,000 projects by the time he retired in 1973, seven years before he died.

With mastery of plan and proportion, his love of curves, and his dramatic flair and understated elegance, Williams produced attractive homes and public and commercial buildings in a range of historical styles, from American Colonial through Tudor, Spanish, Regency, and Ranch.

|

|

|

How is it that Williams proved so successful in an era when few black people became prominent in any profession, let alone one that required close contact with wealthy white folks and free use of their funds? As Williams later conceded, “I've had a lot of fun, spending other people's money.”

Hard work and determination had much to do with his success, of course. He mastered the art of drawing upside down so he could sit across the table from his white clients rather than next to them, which some might have found overly intimate. He worked 22 hours without sleep or food to complete plans for that auto magnate, winning a job that would set him up as one of Los Angeles' leading designers of fine homes.

Design talent also helped. Williams' buildings are striking, and many are gorgeous.

Is this just another tale of a Horatio Alger?

Perhaps. But there remain puzzling aspects to the Paul R. Williams tale, among them: How did it happen that this pioneering African-American architect, a mentor to young black architects, won the disdain of some civil rights activists? And why is it that his modern buildings are often seen as an afterthought in his career?

Williams' modernist legacy is remarkable for its diversity and quality, as well as its sheer number of projects. It ranges from many individual homes to a modern tract, SeaView, in Rancho Palos Verdes. It includes several public housing projects, the Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, plus banks, office buildings, and hotels, including his modernization of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Even his Period Revival houses were historical only in outward dress, architect Wesley Henderson wrote in his Ph.D. thesis. “His period exteriors wrapped around quite modern floor plans,” Henderson noted.

Williams fortified his modernist bonafides by authoring two books of low-cost house plans for returning World War II GIs. For one, he even got Richard Neutra to contribute a design.