Eichler Architect, Bob Anshen: Self-Made Man - Page 3

Anshen may have been a bit of a Marxist, but he appreciated good living too well to begrudge the rich their luxuries, especially their architectural luxuries. Instead, he faulted them for not spending enough on quality architecture.

"Even wealthy people hesitate, for some strange psychological reason, to spend vast sums of money on a dwelling," he wrote in 1956. "When one is rich," he continued, "it is just as ostentatious to pretend that one is poor, as it is ostentatious for one who is poor to pretend to be rich."

Anshen had another run-in with the authorities during the war years—but this time, Olsen remembers, he rather enjoyed it. An official for the State Board of Architectural Examiners, reading about the Davies house and noting that neither Anshen nor Allen were licensed, called on Anshen in Vallejo.

After a few drinks and dinner, according to court records, the official asked Anshen how much he might pay to see the answers for the architects' licensing exam. "Oh, come, come. They are worth more than that to you," the official chided when Anshen suggested $150.

Anshen called the police and ended up acting out a drama for their benefit. Shortly thereafter, in the dining room of San Francisco's Mark Hopkins Hotel, Anshen handed the architectural examiner an envelope with ten $20 bills—after waving the wad in the air "to make sure he was seen," according to Olsen. Officers swept in for the arrest.

Once the war ended, Anshen and Allen were back in business, designing several small homes.

They also got Davies to finance a project they hoped would transform homebuilding in America—'factory-fabricated houses' using lightweight, fiberglass 'stretched skin panels' of their own design that were bolted together on site. Only one was built, in the Berkeley hills. They blamed the high cost of materials and the reluctance of builders to adopt a new technique.

During their career together, Anshen and Allen designed perhaps two-dozen more conventional custom homes, several thousand modern homes in tracts for Eichler and the San Francisco Peninsula developers Mackay and Gavello, and townhouses at the Golden Gateway redevelopment near San Francisco's Embarcadero Center. They designed small offices, retail, industrial buildings, several garages, and a small hotel, circular in plan, that San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen dismissed as a "rusty donut."

The Silverstone house in Mexico, which Architectural Record admiringly described as "a cross between a Mayan temple and the things Miss Carmen Miranda wears on her head," used freeform-curved concrete beams, cast on site, to support a gabled roof with a skylight filling the ridgeline. Garden rooms alternated with walled rooms and opened onto tropical gardens and waterfalls. "A landmark of 20th century modernism," architectural historians Donald Leslie Johnson and Donald Langmead later wrote.

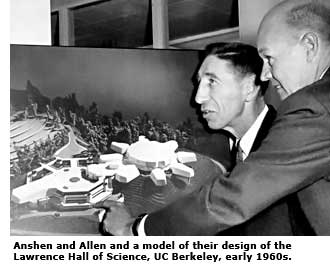

As the firm grew from a single floor and a handful of employees at 461 Bush Street to three floors with about 35, they took on larger projects: the 22-story International Building, the Bank of California (601 and 400 California Street, respectively), the Chemistry Building and Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley, and the beautifully sculptural, concrete visitors center at Dinosaur National Monument in Utah.

Both Anshen and Allen supervised the design of projects, working with teams of associate designers and draftsmen. Allen himself was a superb draftsman. Not Anshen. "Whenever he would do a drawing in the office, he did everything a young draftsman tried not to do," Ray Kappe remembers. "He would burn it, and stamp it upside down."

"Bob was an idea-a-minute guy," Parker remembers. "Ninety-nine percent of them were nonsense, but one percent were genius. Steve, in his careful way, was wonderful at recognizing the one percent."

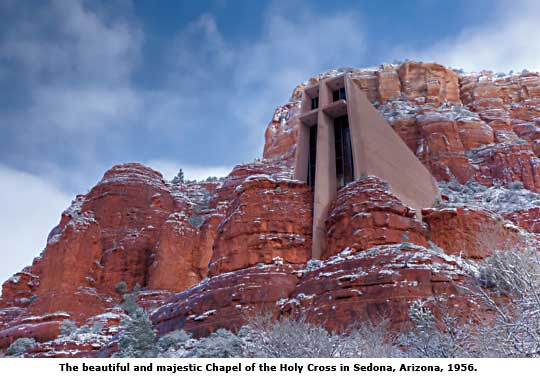

"Bob was quite a talent, but a talent more from the standpoint of having ideas or concepts," Kappe says. "I can remember the Sedona project. He walks in one morning with a couple of lines, and that was the project. It was a beautiful project. There wasn't a lot to it . . . But it ended up as an architectural masterpiece."

Anshen and Allen gave the firm's architects creative freedom—within limits. "He gave architects a lot of leeway, yes," says Walter Brooks, who worked on Eichler homes in the early 1950s. "But he also gave them attention and watched over what they were doing."