Eye for the Fantastic

|

|

|

As Michael Murphy recalls it, he'd spent all of one night—one night—in Palm Springs, and that's when he was eight years old.

But the memories lingered and emerged many years later—in very un-sunny London, of all places, where Murphy was working as an architect. He began to sketch, and what came out looked nothing like Big Ben.

|

|

|

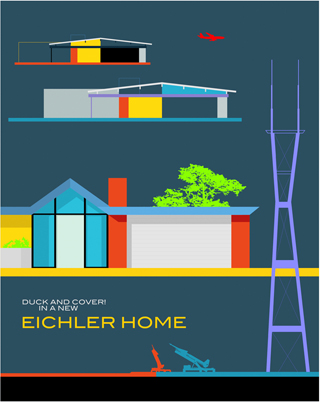

There was desert—endless, flat, with surrealistic vanishing points and ragged mountains in the distance. There were curvaceous houses of concrete, glass, and steel, with rooms cantilevering bravely into space. And there were airplanes, airports—and at least one flying saucer.

Murphy began selling his prints through London galleries, and people were buying.

"They were impressed by the California desert," Murphy says. "Europeans in general—not every single one of them—they love that concept of the American road trip, and the desert, the roads out to nowhere."

"I was selling one a week in a gallery in Notting Hill. It was not enough to quit my job and say, 'To hell with everyone, I'm an artist now.' But it was very rewarding."

|

|

|

|

|

As a project architect overseeing construction and budgets, Murphy had worked on some spectacular projects in both Ireland and England—public buildings, the Dublin headquarters of eBay, and high-end modern-style homes.

It was satisfying work, exciting even—but Murphy was never the designer, never the one in charge. With art, he was.

"Going from being a project architect, working on good projects, to something that was completely mine, I had complete ownership of, was very fulfilling."

Today, back home in San Francisco, Murphy hopes to keep the artistic momentum going. So far it seems to be working.

Murphy, an easygoing guy, spends his time painting in his home studio, sketching, and creating digital images, mostly of buildings, that he turns into giclée prints in editions of 100. His wife, Marta Alabau-Marques, also an architect, is the one who brings in a steady paycheck.

"I've gotten a lot of encouragement from my wife. She recognized that I was a happier person doing this, and that made her a happier person," Murphy says.

Murphy sells his work primarily through his website, and through a few shops in Northern and Southern California.

Architect Carolyn Kiernat couldn't help but notice the first Murphy print she ever saw. She was walking by Zinc Details, a modern furnishings shop on the City's Fillmore Street, when she spotted in its window an image of a building she'd just worked on—an obscure building at that.

It was Fire Station 1, a red box with banded windows on Howard Street that will soon be torn down to make way for the expansion of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Fire Station 1 is the sort of everyday modern building that few people love or even notice—except true fans.