How Ad Men Found Freud

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today, when every swipe of a finger, every click on a mouse reveals our deepest desires to any ad man willing to pay for the information, it's tempting to think of the 'Mad Men' advertisers of the mid-20th century as amusing figures from a culture that was far more optimistic than ours.

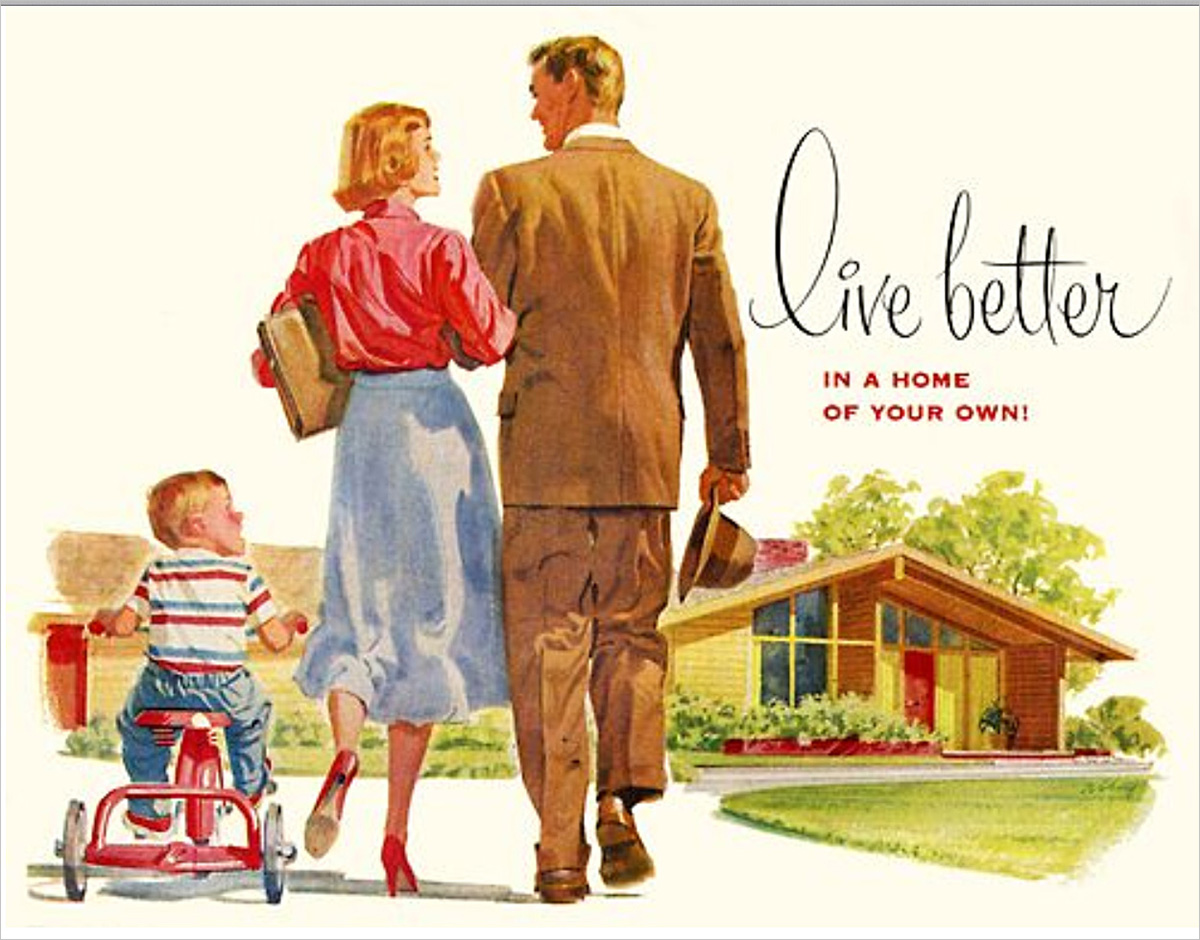

Magazine ads from the 1950s and 1960s can suggest a more placid time, homes with white picket fences, families gathered around the hearth, Fido. 'Live Better—in a Home of Your Own!,' one ad promises, showing an Eichler-like abode.

But don't be fooled.

As composer Leonard Bernstein's famous symphony from 1949 suggests, this was 'The Age of Anxiety.' Communists were on the rise. The atomic bomb threatened. Bomb shelters were being built along with backyard barbecues.

All those upbeat ads from the period? Like a good stiff drink, like psychoanalysis, they were designed to assuage the pain.

And who helped design these ads? Psychoanalysts.

"The use of mass psychoanalysis to guide campaigns of persuasion has become the basis of a multi-million dollar industry," author Vance Packard reported in 1957 in his bestseller The Hidden Persuaders.

As Packard revealed to his already worried readers, psychoanalysts, psychologists, and other social scientists were being recruited by every ad firm and marketing outfit in the Yellow Pages to study real people—in depth.

"We are frequently revealed, in their findings, as comical actors in a genial if twitchy Thurberian world," Packard wrote, referring to comic author James Thurber, creator of a world of befuddled humans and flop-eared hounds.

"Typically [the social scientists] see us as bundles of daydreams, misty hidden yearnings, guilt complexes, irrational emotional blockages…We amaze them with our seemingly senseless quirks, but we please them with our growing docility in responding to their manipulation of symbols that stir us to action."

The father of what became known as 'Motivational Research'—in fact, he claimed to have invented the term—was a psychologist from (where else?) Vienna, Ernest Dichter, bubbling with enthusiasm, sporting bow tie and horn-rimmed glasses.

To gather data, Dichter would pile children in front of TVs to watch commercials while filming and taping their every squeal and yawn.

'Psycho-panels' of grownups would be intensively mined to learn about each neurosis, each desire, each purchase.

Dichter told a group of ad men in 1941 that ads need to "manipulate human motivations and desires and develop a need for goods with which the public has at one time been unfamiliar—perhaps even undesirous of purchasing."

Kind of creepy, huh?

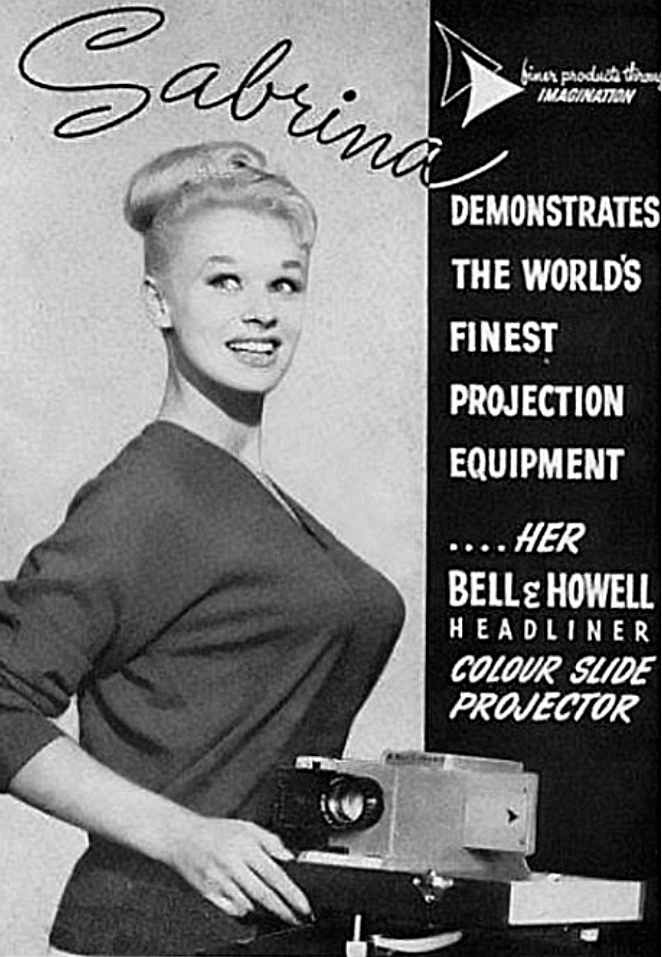

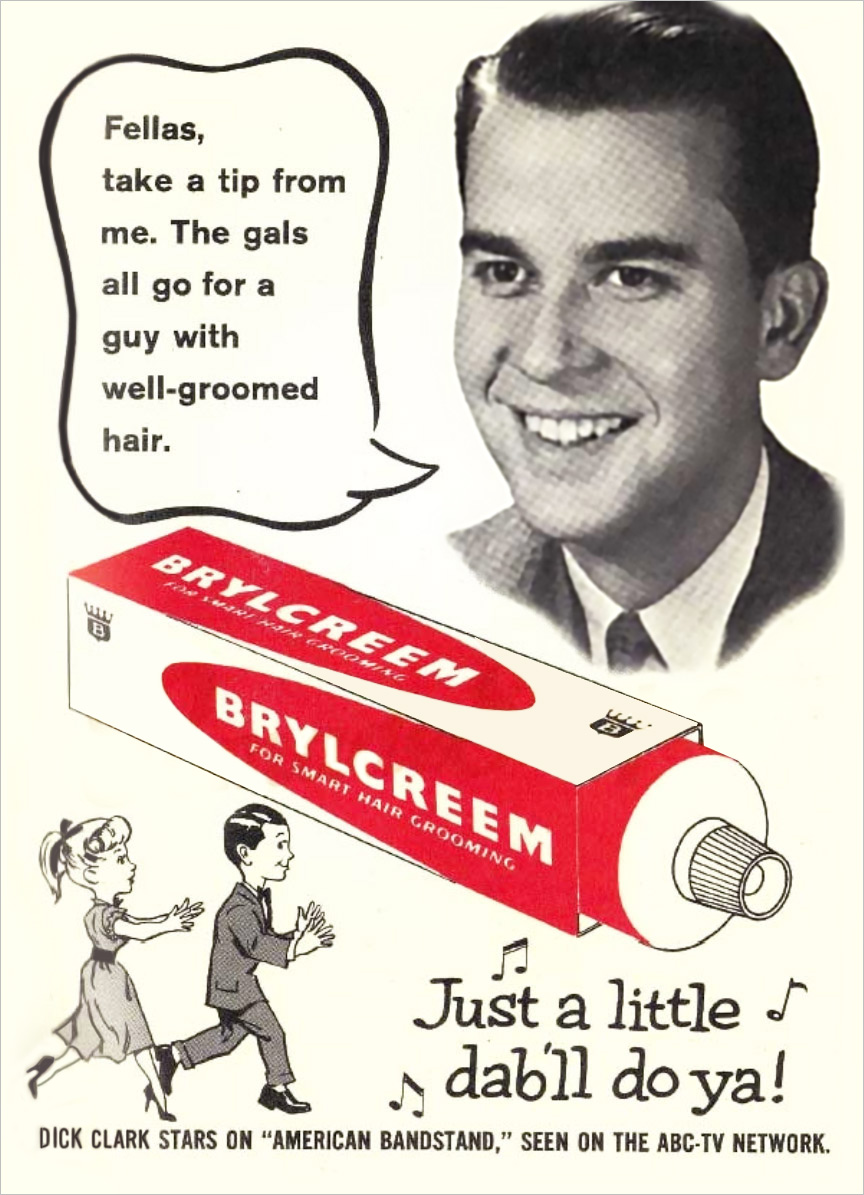

Still, it's hard for the nostalgic among us not to enjoy these vintage ads—both for what they say, and how they say it.