Playing With Space

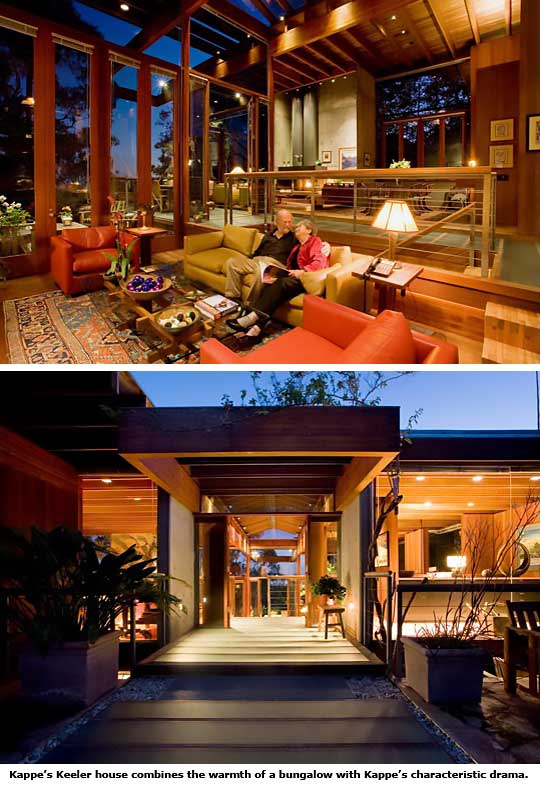

Ray Kappe's houses can come across as quirky. Space in a Kappe home is layered and complex. His houses tend to be many-leveled, complete with half steps, with each level open to the others, visually and in other ways.

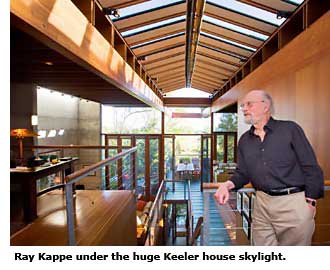

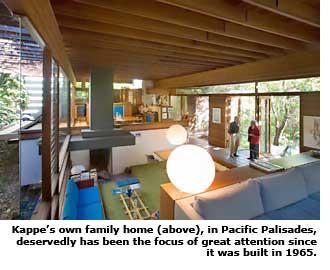

Kappe's own home, which is entered through a hidden door beneath a cave-like over-hang and alongside a creek, is made up of seven distinct levels, including a dining room and a den that overlook a living room that in turn cantilevers over Kappe's studio. There are no railings to prevent a fall.

"I always have places where people can get hurt," Kappe says, deadpan, in a deep baritone that has charmed, fascinated, and occasionally infuriated generations of architecture students. "I'm good at that. I believe it makes people look a little bit more, which is good. It's better than being protective, and being safe."

Is Kappe just another master architect designing playful homes for the sybaritic? Far from it. Infusing more than 50 years of work is a dream to design communities for the mass public. His custom houses are experiments into ways that can be done, with modules designed to be replicated elsewhere.

"I was interested always in low-income housing and hoped I would have the opportunity to do it. It never happened for me," he says, adding, "You don't always do what you hope you might get to do."

Kappe, 83, has designed more than 100 homes in his career, won numerous awards, been named a fellow of the American Institute of Architects, and founded a leading architectural school.

But most of his designs for mass housing remained on paper, including prefab, modular student housing for Sonoma, and a 1,000-home plus multi-unit project for Fresno complete with greenbelts. Kappe called for clustered housing to preserve open space, pathways, and communal spaces and community centers to encourage sociability.

He did succeed, however, in developing several plans for city improvements that were implemented, in whole or part, in Inglewood, Beverly Hills, and Santa Monica.

Ironically, the closest Kappe got to producing mass housing came at the beginning of his career, when he briefly helped design tract houses for Joe Eichler as an entry-level architect with Anshen and Allen. "It's tough to find a developer who has a mindset something like Eichler," Kappe says.

Still, the 100 or so houses that Kappe did produce are not only beautiful and innovative, but they remain chock full of ideas, some of which Kappe continues to pursue. He was a pioneer in prefabrication, building several of his houses out of pre-manufactured parts that were trucked to the site and craned into place.

Kappe, who spent his boyhood in Minneapolis, came to Los Angeles with his parents, who ran a women's clothing store, at age 13. He found the design of his junior high curiously appealing; it was designed by Richard Neutra.

In 1948, after two years with the Corps of Engineers, Kappe began studying architecture at the University of California Berkeley on the GI Bill. The Bay Area was a hotbed of modernism, and Kappe spent half a year with Anshen & Allen, in 1950, while at school.

Newly married, Kappe returned to Los Angeles in 1951 to pursue his career because, he says, "There seemed to me to be more opportunity here than up north."

Kappe absorbed the Bay Tradition's appreciation of wood and its interest in vernacular and Arts & Crafts design. As Kappe told his protégé, Bay Area (by way of Los Angeles) architect Robert Swatt, "You're going to bring a little of Southern California up north with you, just as I brought a bit of Northern California down south with me."

Two years in the office of architect Carl Maston saw Kappe designing apartments, tract housing, and so many glass-fronted shopping strips he never knew which ones got built and which did not. Kappe formed his own small firm -- it ranged from three to five draftsmen -- in Brentwood in 1953.

For the first ten years, Kappe's homes were mostly simple, post-and-beam. Kappe, who was always interested in structure, and new ways of building, occasionally used steel frames, but his clients most often opted for wood to save money.

By the early 1960s Kappe developed a structural system that sunk six or eight steel-reinforced concrete or wooden towers, which often ran the height of the building, into the ground. The towers carried the loads and provided seismic stability while supporting immense laminated wooden beams that allowed the home to float like a bridge over the land.