On the Road Again: Trailers

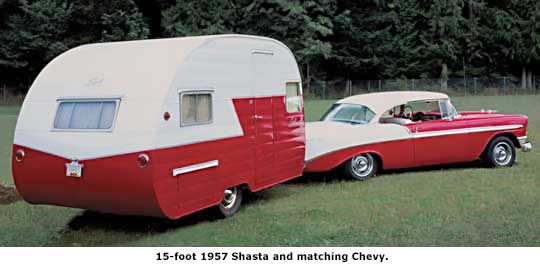

They're small, sleek, and often silvery-skinned, superbly engineered, and with zero wasted space. People can live in them and, when it's time to move, can move in them. The best among them are stylish, even beautiful. More than anything Le Corbusier ever designed, they are true 'machines for living.'

Yet in architectural history, mobile home travel trailers get no respect.

Architectural historians brag about the profession's commitment to mass-producing houses for the poor and working class—an effort that has been much promised but rarely achieved. Richard Neutra won praise for his low-cost World War II housing in San Pedro, Gregory Ain for his Mar Vista tract in Venice, aimed at ex-GI's with young families. Yet architectural historians never include travel trailers in their paeans to 'social housing.'

But throughout the Depression and in the immediate postwar years, thousands of Americans found shelter in simple, efficient, and inexpensive travel trailers. Trailers were, quite simply, a form of vernacular, working-class modernism inhabited by people who had never heard about 'form and function.'

It is true, of course, that trailers are not technically houses—nor, in some views, architecture at all. Their designers remain largely anonymous. Trailers don't fit in the standard architectural paradigms. There is no theory of trailers. Like tract houses, which have also been excluded from much of architectural history, trailers are not quite respectable. They're a form of 'low art' at best, associated with 'trailer trash,' at one end of the spectrum; and with lower-middle-class vacationers wearing plaid shorts at the other. Despite their streamlined look, there's something about trailers that can seem irredeemably square.

Trailer fans, however, are taking heart, because trailers are starting to gain attention among architects, historians, and the common herd. "These trailers were the original small living spaces," says Ed Lum, a graphic designer and trailer aficionado who's as square as a jellyfish. "Now it's come back that people are looking for small living spaces. So what was retro is now modern again." Lum lives in a trailer in what may be the country's only trailer park that has been declared a historic monument, Monterey Trailer Park in Los Angeles. "A lot of architects are now getting into this," he says. "They're recognizing them a lot more than they used to."

California, not surprisingly, is in the forefront of the travel trailer renaissance. In Los Angeles, architect Jennifer Siegel, who owns an Airstream trailer, designs prefabricated homes and offices on wheels through her firm, the Office of Mobil Design. And artist Andrea Zittel, who's based in Joshua Tree, in the high desert east of Palm Springs, has created many trailer-like art objects—including the tiny 'A-Z Escape Vehicle' ("a refuge from public interaction") and the 'A-Z Wagon Station' ("an evocation of the Old West covered wagon") that are more thought experiments than marketable products.

In her art, Zittel poses the question: how small can a space be and still be considered a 'home'? That's a question trailer manufacturers have been trying to answer since the 1920s. Perhaps the best way to trace their efforts—and to find out just how modern travel trailers can be—is to visit Funky Junk Farms, a collection of vintage trailers and more, at two sites in Southern California.

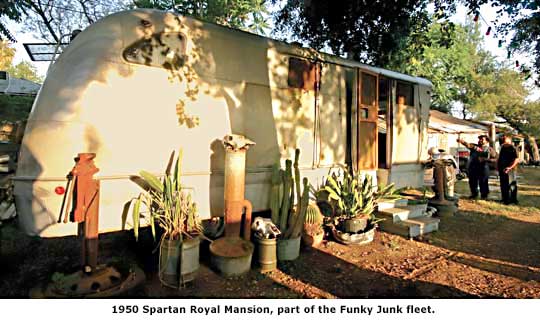

"Look at them," says John Agnew, the proprietor of the farm's main 'campus' in Altadena, which is filled with trailers of varied sorts in varied stages of repair. "They're beautiful. They're like big bungalows on wheels."

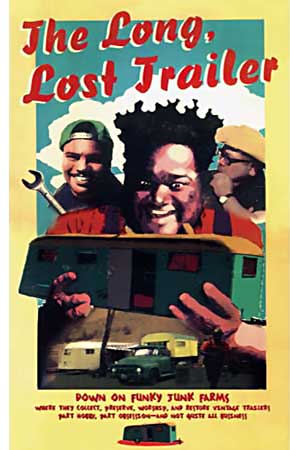

At the farm, a former tropical fish hatchery called the Altadena Water Gardens, Agnew, Lum, and their friend Steve Butcher collect, preserve, worship, and restore vintage trailers. Butcher, whose background is in vintage auto restoration, also runs a large indoor trailer rehab hospital in the Ventura County town of Fillmore, an hour away.

Agnew's Funky Junk Farms is both a museum and his home. The operation is part hobby, part obsession, and not quite all business. "These are art pieces to us," he says. "This is a gallery."