Road to Bohemia - Page 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It's not surprising then, to understand why so much of the writings of Miller, as one example, focused on the plight of the starving artist, who came to represent a person who was more real, more authentic, more just, more anti-war and anti-materialism than the rest of American society.

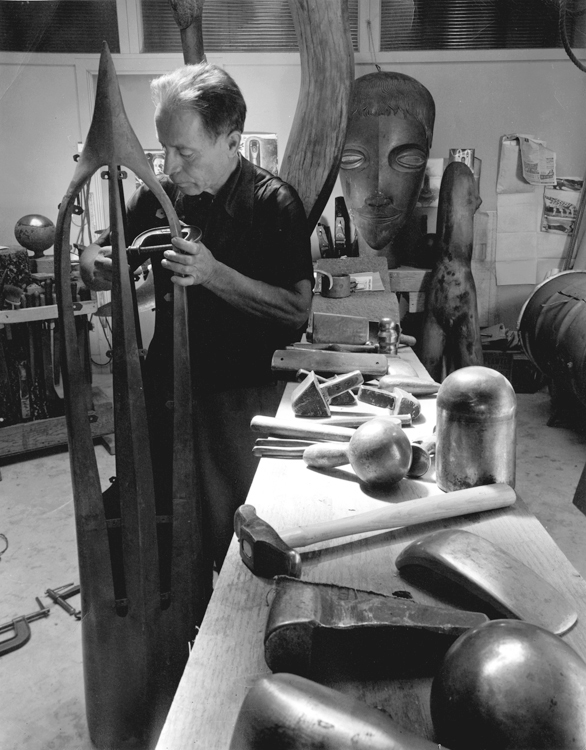

To Miller, who wrote about each man, both Varda and Bufano were prototypes.

"He is never the critic, always the planner and builder," Miller wrote of Bufano. "He never wastes a moment; he carries no impedimenta, is always fit and ready to enter the fray. In one being he combines dreamer, worker, athlete, gladiator, adventurer, monk, saint, and statesman."

In his admiring profile of Varda, Varda: the Master Builder, Miller writes of a man "always wreathed in a cherubic smile," who discusses Oriental art, obscure Baroque composers, and ancient Greek philosophy.

"There is one thing that is anathema to Varda and that is waste. It explains why he takes such delight in plundering the refuse heaps, and from the plunder creating veritable mansions of light and joy," Miller writes, describing Varda and his wife Virginia's Red Barn in New Monterey.

It was Varda who introduced Miller to Big Sur and was responsible for his move there in 1944. About Big Sur, where he lived in a tiny cabin, Miller wrote, "For the first time since my trip to Greece I felt in total communion with nature, with the infinite, the gods."

Miller, like Varda, was generous even when he was broke. When he did get some cash he shared it with other artists, and wanted to create a community of artists—which he did, attracting many to Big Sur.

Among the dozens of scenes that made up mid-century bohemia in the Bay Area, the one that took place at a Frank Lloyd Wright house in Hillsborough is worth mentioning—and not just because it got going shortly after the new owners of the home expelled Joe Eichler and his family, who had been renting it during the war years.

Soon the Bazett house, presided over by owners Betty Frank, a devotee of Eastern thought and yoga, and husband Louis was attracting for visits and parties such people as Jack Stauffacher, the modernist printer whose Greenwood Press published Henry Miller, and his brother, experimental filmmaker Frank Stauffacher, whose 'Art in Cinema' screenings in San Francisco were another node for artists and intellectuals.

Also coming to the home were Warren Callister and his erstwhile architectural partner Jack Hillmer, Varda, and others.

"It was the house that drew them, absolutely," Betty Frank told the Eichler Network a decade ago. She added, "It has attracted interested people, artistic people, and it's just very uplifting to live in a piece of art."

Telesis, a group of idealistic architects and planners, met regularly at the Bazett house, Callister and Hillmer recalled in interviews in the early 2000s.

"Telesis is not interested in utopias," its mini-manifesto stated in 1943, "but is vitally interested in the improvement of the living environment here and now, under existing social and economic conditions, and with the present legislative machine." "One of our major interests," Hillmer said, "was to make the world better."

Photography: Fred Lyon, Ernie Braun, Brian Guiney, Jerry Burchard; and courtesy Betsy Stroman, Henry Miller Memorial Library, Betty and Louis Frank family