Saving the '60s

"That building can't be historic -- I remember when it was built!" Ever heard that said about a building near to your heart?

As time marches on and we get older, so do the landmarks we love -- unless they're torn down first.

The year 2010 marks an important milestone in the preservation of mid-century modern architecture, as structures built in 1960 reach the ripe old age of 50. While turning 50 strikes fear in the hearts of many -- especially in Los Angeles -- it actually can be reassuring for important buildings.

In historic preservation, 50 years is the general threshold when buildings and structures are officially considered old enough to have acquired historic significance, particularly in terms of the National Register of Historic Places. While Los Angeles has always pushed the envelope by recognizing significant places prior to the 50-year mark, crossing this threshold should make it less of a struggle.

The all-volunteer Modern Committee (ModCom) of the Los Angeles Conservancy has dealt with this hurdle since its founding in 1984, long before the renaissance of mid-century modernism.

"Early on, the idea of preserving modernist resources was hard for many people to swallow," says John English, an architectural historian and longtime member of the ModCom. "In the 1990s, buildings of the '50s gained credibility, but people couldn't even think about the '60s as a preservation issue.

"Now, here we are. This is it. There is no longer any doubt that enough time has passed for these structures to merit preservation."

1960 arrives

"Suddenly, it's 1960!" So went the sales slogan for 1957 Plymouth automobiles, the entire line newly designed with bold, futuristic features to careen car lovers into the bright new decade of the 1960s.

The '60s were certainly a unique and exciting period in the history of Los Angeles and the country. Against the national backdrop of the Kennedy era, the civil rights movement, the space race, and the Age of Aquarius, Los Angeles developed its freeway system, the aerospace industry flourished, and the population boomed. The city truly came of age as a modern metropolis and began its rise as a cultural capital.

Preservation also took hold in the '60s. The City of Los Angeles created its Cultural Heritage Ordinance in 1962, becoming one of the first cities in the U.S. to do so. The National Historic Preservation Act followed in 1966.

"It was during this decade that Los Angeles first became a 'world city,'" says English. "It was also when we fully realized much of the postwar promise that had been building up steam throughout the late '40s and the '50s. Commercial architects really hit their stride in terms of large-scale development. And Los Angeles International Airport embodied the jet age. When you arrived in Los Angeles, you knew that Los Angeles had arrived."

Despite its early foray into the world of historic preservation, Los Angeles doesn't have a strong track record in protecting its historic resources, particularly those of the 1960s. The region has lost a number of important 1960s structures, from commercial buildings to significant homes.

The elegant Irving Stone residence in Beverly Hills (Richard Dorman & Associates, 1961) was demolished in 2008 as part of the nationwide teardown trend. The former Century City office of Welton Becket & Associates, one of the most prominent and influential architectural firms in Los Angeles, particularly in the '60s, was razed in 2005. Many others have fallen to the wrecking ball, have been altered beyond recognition, or currently face demolition (see sidebar stories here for two current examples).

Fortunately, many other 1960s landmarks have been saved from demolition, proving their value and viability. The Conservancy has advocated for mid-century modern resources since its founding in 1978, and its Modern Committee has been at the vanguard of the movement for 25 years.

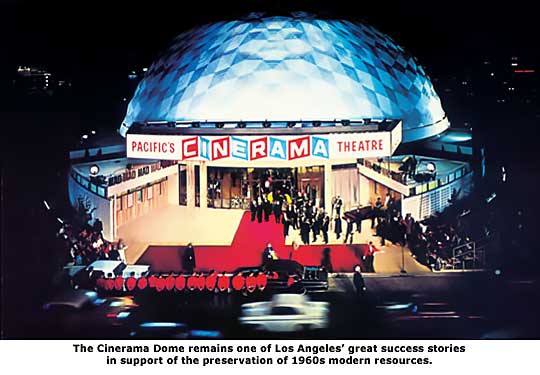

Among the city's greatest success stories is the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood, designed by Welton Becket & Associates. Featuring the world's only all-concrete geodesic dome, this futuristic theatre also had the world's largest movie screen when it opened in 1963. After a multi-year effort by several preservation groups in the 1990s, the iconic Dome was preserved as the centerpiece of a new -- and wildly successful -- theatre complex.

Preservationists have expanded their efforts beyond single '60s resources to entire neighborhoods. Historic district designation is in the works for the Balboa Highlands Eichler tract in Granada Hills (A. Quincy Jones, Frederick Emmons, and Claude Oakland, 1963-'64), a neighborhood ModCom featured on a 2000 tour of modernism in the San Fernando Valley.