Sexy, Curvaceous Roofs

|

|

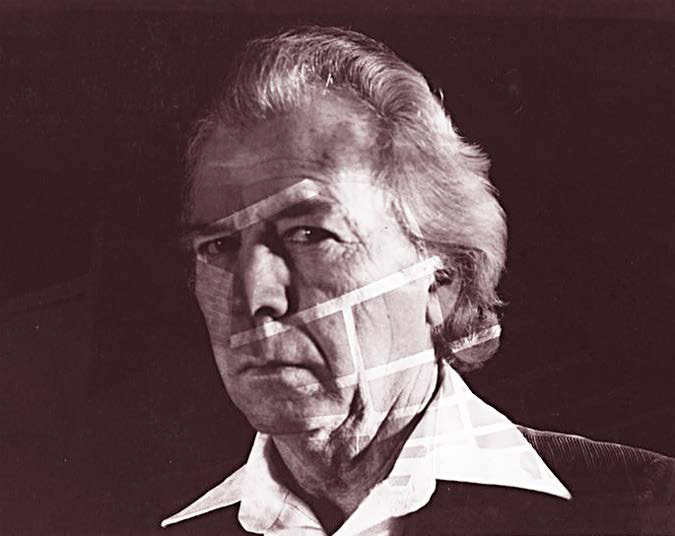

(including the Bates House pictured here from 1944), but Walter S. White is still a well-kept secret. His new exhibition may change all that. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s often been said that the hat makes the man. In the work of Walter S. White, the astounding but too-little-known architect, the hat certainly makes the house.

White (1919-2002) did most of his work through the 1940s and ‘50s in Palm Springs, Palm Desert, Indio, and other Coachella Valley cities. He then moved to Colorado Springs, continuing to turn out innovative, attractive structures, only to move back to California in later years.

An exhibit honoring White and his work, ‘Walter S. White: Inventions in Midcentury Architecture,’ runs through December 6 at UC Santa Barbara’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum. The exhibit is curated by Volker Welter, a professor at Santa Barbara, whose catalog of the same name will be published in January.

The university, conveniently enough, is home to the Walter S. White archive.

“White’s designs for the Coachella Valley desert cities of Palm Desert, Indio, La Quinta, and Palm Springs in the 1940s and 1950s addressed the extreme climate with thrilling, expressionistic forms that took inspiration from the natural landscape, while proposing new, ecologically sensitive, and inexpensive construction methods,” the museum states on its website.

The show, which followed a seminar on White given by Welter, features about 200 works, drawings, plans, photos, and one model—of a very characteristic White object, a hyperbolic paraboloid roof.

Throughout his career, White designed roofs that can cause people to stop and stare—and smile. He even patented a method for constructing curved roofs, says the museum’s architecture and design collection curator, Jocelyn Gibbs. “It was for roof construction using dowels that allowed him to change the curve of the roof,” she says.

One among many homes that benefited from a classic White roof is the Bates house, which still stands in Palm Desert. Its roof is a series of wavelike curves. Gibbs notes that the roof is turquoise colored. “It’s pretty great.”

But White, who didn’t get formal architectural training and didn’t get a license until he was nearing retirement, did more than design sexy, curvaceous roofs.

A man who was seriously interested in low-cost housing (even designing kit houses sold by Sears that he said could “be assembled in a matter of hours,” White was also ahead of his time in designed passive solar houses.

White worked early on for such pioneering Southern California modernists as Rudolph Schindler and Harwell Harris and was deeply influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The museum decided to focus on White because he was an early modernist doing interesting work whose career remains relatively little known, Gibbs says. Yet he was prolific, often as a developer-designer turning out hundreds of homes in the desert.

As the architectural historians looked into White’s work, she says, “We were really surprised at the number of things he built.”

For more on the ‘Walter S. White: Inventions in Midcentury Architecture’ exhibit, click here.