SoCal Modern: At Home in the New Frontier

'Mid-century modern' is often used as a catch-all term to describe design from post-World War II America. But take a closer look—and the 1960s truly sets itself apart with a new realm of ideas that set the stage for a new era.

As residential architecture from the 1960s begins to turn 50 this year, the time is right to pause and appreciate some of its unique qualities.

As with other building types—commercial, retail, civic, ecclesiastical—residential design in the 1960s in many ways brought to fruition concepts that had been building since the 1950s, from innovative use of materials to general optimism and prosperity.

In some cases, young families who had hired emerging architects to build modest first homes in the late 1940s and 1950s recommissioned the same architects in the '60s to build larger homes for their growing families. Southern California architect Edward Fickett, for example, designed two homes for George and Miriam Jacobson: the first in 1953 and a second, larger home in 1966.

The population explosion in the 1960s—particularly in Southern California, and particularly in the suburbs—created a surge in demand for affordable homes. The well-designed, mass-produced homes by builders Cliff May and Joseph Eichler, architects Palmer and Krisel, and others had become firmly entrenched as a segment of the building industry. Similar developments of tract homes were scattered all across America, typically on the fringe of metropolitan areas. They boomed during the 1960s as communities stabilized with amenities to support suburban life, from schools and churches to office parks and shopping malls.

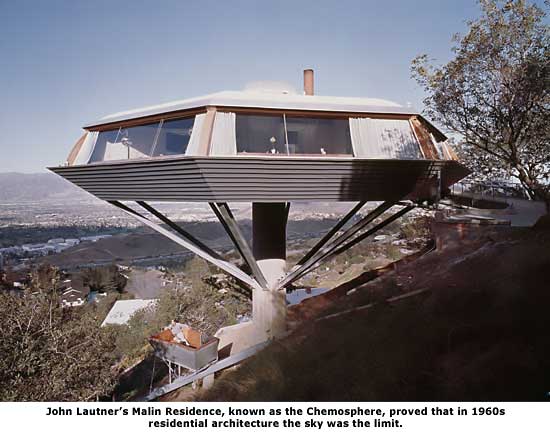

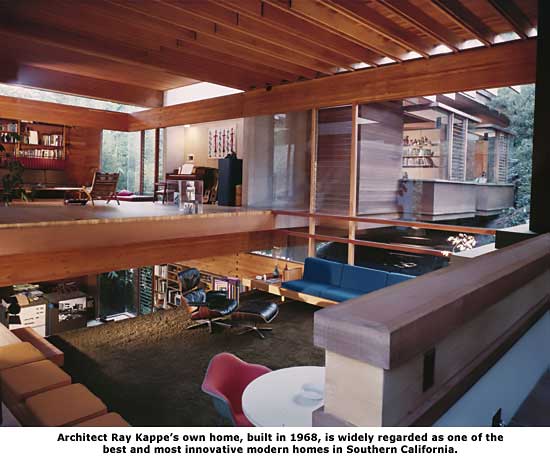

At the same time, designers actually built homes with more daring lines, organic textures such as flagstone, and space-age materials including aluminum. Flat roofs often gave way to dramatic peaks, such as the steep central gables built by Jones & Emmons for the A-frame roofs of some 1960s Eichler tracts.

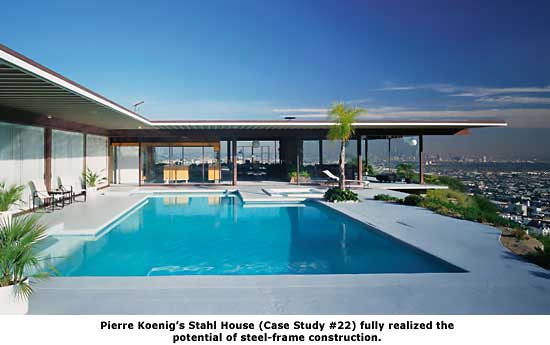

One of the hallmarks of the well-designed, affordable housing concept in postwar America was the Case Study House program (1945-1966) for 'Arts & Architecture' magazine. Concepts that hatched in the early years of the program were finessed in its later years.

For example, while architect Raphael Soriano refined the use of steel-frame construction in residential architecture (well publicized earlier by Richard Neutra in 1929's Lovell Health House), Pierre Koenig's Case Study Houses #21 and #22 stretched the concept. Koenig's 1960 Stahl Residence (CSH #22), perched high above Los Angeles and immortalized in photographs by the late Julius Shulman, has become one of the most iconic pieces of residential architecture in the world—and was made possible only through innovations in steel-framed housing.

Architect Beverley (David) Thorne also used steel framing in Case Study House #26, built in 1962-'63 for the Harrison family in San Rafael. Co-sponsored by Bethlehem Steel Company, this structure demonstrated how steel could be used on a difficult hillside site, hoping to show that it could be as affordable as traditional wood construction.

Case Study House #25, the wood-framed Frank House by Killingsworth, Brady, Smith and Associates, was completed in 1962. With its dramatic double-height interior courtyard, this home includes signature Edward Killingsworth concepts that relate to his earlier work yet had matured in this 1960s testament to affordable, modern design.

The concepts and accomplishments of the Case Study House program were indeed celebrated among intellectual circles in architecture. They were still considered avant-garde by much of mainstream America, however. Other residential styles developing at the same time in the mid-20th century—including Hollywood Regency and the Ranch house—planted one foot in the past while still embracing the '1960s lifestyle.' Trousdale Estates, a development by builder Paul Trousdale, offered examples of another modern yet less severe style by architects such as Allen Siple and Wallace Neff.

In perhaps the most blatant rejection of 'glass-box' modern, legendary Hollywood Regency designer John Elgin Woolf and his partner Robert Koch transformed Craig Ellwood's Case Study House #17 (1955) in 1962. In addition to reconfiguring the living spaces, they added Woolf's signature double-height entry topped by a mansard roof, as well as a Doric colonnade near the swimming pool.