Soul Searching: Photographer, Leland Lee - Page 2

Lee still laughs at some of what he saw while working with Shulman, especially shoots with the legendary Richard Neutra. "Neutra, he wanted everything his way," Lee says.

"Many, many times I would be witness to conflict," Lee recalls. "Julius and Neutra were always tugging. Neutra wanted to look through the camera and make sure everything that was bad was hidden. They had a symbiotic relationship. One could not do without the other."

But Lee's true importance is due to the work he did once he went out on his own. His photographs appeared in Architectural Digest, House and Garden, the Los Angeles Times, and many more periodicals and books.

For almost 40 years Lee photographed architecture and landscaping, as well as product shots and more. He shot banks in Los Angeles, tract homes in Santa Clarita, and interiors in mobile homes. He did shoots in Chicago, the East Coast, and overseas.

In the late 1970s Good Housekeeping had Lee focus on film stars and their homes, including Kirk Douglas, Dinah Shore, Burt Reynolds, Cheryl Ladd and, "in a political ploy," he says, Nancy Reagan. Lee shot Mary Tyler Moore's Malibu home, Sonny and Cher's first mansion, and the home of Nancy Reagan's fashion designer James Galanos, with its zebra-skin throws and couture-grade satin covering every surface.

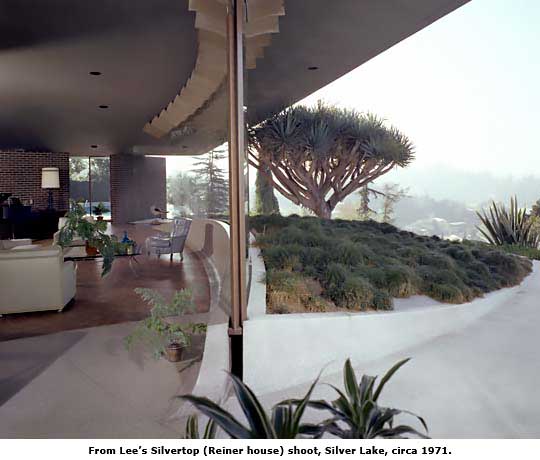

But Lee's tastes ran to modern, and that is where he really made his mark.

Shulman, who died in 2009, and such stalwarts as Ezra Stoller, Roger Sturtevant, Morley Baer, and Ernie Braun are familiar names to fans of modernism today. But consider all the other names that appear alongside photos of modern homes from the 1950s and '60s—Roy Flamm, Dean Stone, Hugo Steccati, Leland Lee—photographers whose work deserves recognition as much as does the work of so many of the now-forgotten architects with whom they worked.

Lee regards his work as a form of art—he still cringes when he sees his photos cropped by someone else—but one that is in service to its subject. From Shulman, he says, "I learned the importance of recognizing the merits of the architecture, and the mere fact that the architecture itself has its demands. You can't really [photograph] it any other way. It speaks to you.

"The photography should certainly reveal the soul of the house. Every good house has an aspect about it, and your photo needs to speak about that."

Lee, who began his career in the era of bulky flash bulbs, became a master of light—often in such tricky conditions as the Palm Springs desert, where balancing the harsh exterior glare with the warmer interior can be hard. "But sometimes you want that impact of the environment, that brilliant desert light," he says. "It can be dramatic."

And Lee still recalls one shoot along the Pacific Ocean for a residence designed by Edward Fickett. "The sky was brilliant blue and the ocean was a sheet of cobalt, and the wood complemented it, the redwood. It was a moment! You normally don't get that kind of condition out there. The sky will be pallid, and the ocean looks grey. It made the picture. If you made the same shot under different conditions it would have been dishwater."

Working for Shulman allowed the Lees—who had two boys by this time—to move into a rather nondescript home on a steep street above Hollywood. "It was very clean and small, 900 square feet when we got it," Lee recalls. "We kept adding to it. Today it's surrounded by million-dollar houses." The pay was okay, Lee says, but "I didn't want to spend the rest of my life in the shadow of someone as established as Julius."

So at the start of the 1960s Lee went out on his own, forming the Leeside Co. and running it from his home. Contacts with the Los Angeles Times got him work initially. Then he waited. Lee had met everyone in the architectural field while working for Shulman but, he says, "I didn't want to encroach on Julius's terrain."

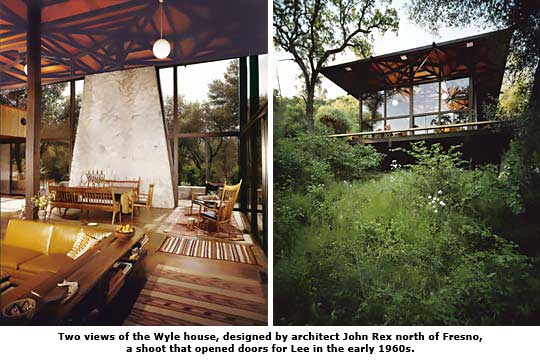

Then came a call from John Rex, of the firm Honnold & Rex, modernist designers of homes, schools, banks, and offices: "'Leland, I've done this wonderful house up in the country. It's probably one of the best things I've ever done. Everybody is after me [to photograph it], all the magazines want to publish it. I want you to have it.'"

"That was my first big thing," Lee says. "It opened doors. It put me on the map."

The house, designed for Frank and Edith Wyle in 1970, with its double-height, glass-fronted living area and rustic stone fireplace ("contemporary elegance for a working ranch," Architectural Digest called it), required Lee to ford three creeks to reach it.