Work in Progress: 19th Avenue - San Mateo - Page 4

The first down came early when a dozen or more houses began to settle, their concrete slabs cracking. The building site had originally been a saltwater marsh that developer L.C. Smith filled. (The neighborhood's street names, by the way—Eleanor, Vanessa, Celeste, and the others—were for members of Smith's family.)

Radiant-heating pipes in the concrete broke and needed to be replaced. "You'd have people coming into your living room with jackhammers," Boris Ragent remembers.

Ned Eichler, Joe's son and a manager of the homebuilding firm at the time, says the problems at Nineteenth Avenue Park were by far the worst the firm had with any of its subdivisions. "Before," he says, "it was a house here, a house there."

More recently, the collapse of the real estate boom sent several homes in the neighborhood into foreclosure. But, Yang says, they have sold quickly. At the top of the market, one home sold for just under $1 million. Today, neighbors say, homes in the neighborhood sell in the $600,000 range.

"It helps that prices have declined," Yang says. "Now young people can afford houses. They're new blood. They're very energetic."

Multicultural living was

a good fit from the start

Cheryl Hylton is convinced that Nineteenth Avenue Park is a neighborhood on the rise. But while moving into its future, she wants her neighborhood to remember its illustrious past.

"What I think is the coolest thing about this neighborhood is how it went along with Joe Eichler's values," she says.

Eichler was known for not discriminating against minorities. Many early residents of Nineteenth Avenue Park were Asians, mostly from San Francisco or the Peninsula, who chose the neighborhood, in part at least, because it was the only desirable place that would have them.

Boris and Dorothy Ragent, residents from 1956, say it was one of the very few integrated neighborhoods in the vicinity. "It was very cross-cultural," Dorothy says. "People were very neighborly and were interested in other cultures."

She remembers one Japanese family whose home was decorated very simply—and always had one piece of art on display, which would change every month. "They did it because the object was to contemplate one work of art at a time," she says.

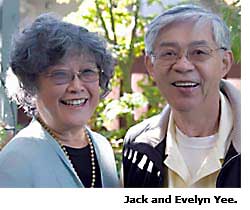

Jack Yee, who grew up living above his dad's laundry in a small Asian district near downtown San Mateo, and his wife Evelyn, his high school sweetheart, decided in 1958 that they needed more room for their two young sons. Living above the laundry would no longer do. "There was no place to run around," Jack says.

Evelyn, an outgoing, humorous woman, and Jack, a quiet but good-natured man who still works every day in his Ching Lee Laundry, a local institution, were far from naïve. They knew there was an invisible line back in the 1950s that Asians could not cross when buying property—the railroad tracks that ran north-south through the Peninsula. "Any black person or Oriental would know that," Jack says. "That's the boundary."

So they visited an open house at a subdivision called Fiesta Gardens—on the acceptable, bayside side of the track. "We didn't even step in the door," Evelyn says. "They said, 'Don't bother. We only sell to Caucasians.'"

"We were hurt!" Evelyn says. "We wanted to go get a house, and we couldn't go in and look at it!"

But just up the road was Nineteenth Avenue Park, which already had a sizable contingent of Asians, ten to 15 families, they say—Chinese, Japanese, Filipino. The Yees joined them in 1958.

It proved a good fit.

• Nineteenth Avenue Park, near the intersection of Highways 101 and 92, is bordered by Joanne Drive to the north, South Grant Street to the east, Concar Drive to the south, and South Delaware Street to the west.

Photos: David Toerge

Story originally published in 2010

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4