Modern Homes Abetted Sexual Liberation

|

The men and (a few) women who developed modern residential architecture in the early and mid-20th century had a lot on their minds:

How should homes function for today’s families? How can they be mass produced inexpensively? What should they look like, now that we are dropping historical pastiche? Can modern living lead to a better society?

But were these architects thinking about something else as well: sex?

British art historian Richard Williams decided to take a look-see. “Where was sexuality in the conversation about modern architecture,” he wondered, and the result was his 2013 book, 'Sex and Buildings: Modern Architecture and the Sexual Revolution.'

|

In March, the California Preservation Foundation, always desirous of perking interest in and entertaining fans of architecture, worked with the modernism preservation group Docomomo and USModernist to produce a lively happy hour conversation on Zoom, ‘Modern Design and the Sexual Revolution.’

It remains online for your viewing. You may never look at your Eichler or Streng modern tract home the same way again.

Williams, speaking from the UK, brought it back to 1920s Los Angeles with architect Rudolph Schindler, “such a raffish character,” who built a home for himself and his wife and another young couple with outdoor sleeping areas rather than bedrooms.

“Two couples living in intimate circumstances,” Williams said, suggestively, and: “a primitive idea of sexual liberation there.”

|

The sleek, glass-and-steel Case Study houses that won so much attention in Southern California a few decades later were explicitly designed for families, Williams said.

But then, what was photographer Julius Shulman getting at in portraying attractive young adults eyeing each other provocatively in these gorgeous settings? The photographer’s “libidinal interpretation,” Williams said, reveals “sexual undercurrents.”

Or how about an unbuilt glass-walled mansion for Playboy magazine’s Hugh Hefner, and the “exhibitionistic and voyeuristic aspect of its circular bed,” (which later was installed in a different mansion design). “You could spend your entire life in the bed,” Williams said. “The bed was the center for operations.”

Returning to California, Williams appreciated the LA and Palm Springs homes of John Lautner, sculptural exercises often in concrete and glass that have proven popular as sets for James Bond movies and other sexy action flicks.

|

These are homes that “seem to be hedonistic,” Williams said. “They were organized around the display of the body. The pool was very important.”

“Like all Lautner houses,” he said of the Elrod house in the desert, “it really pays a lot of attention to the bedroom.”

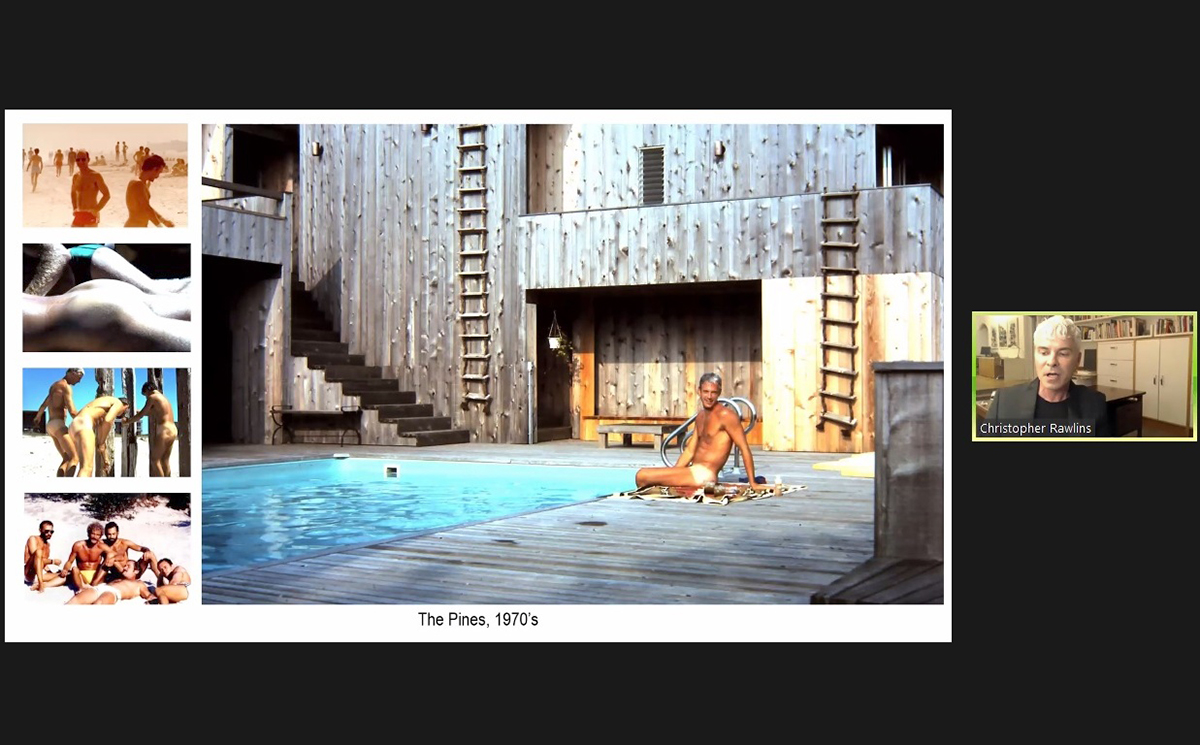

Liberation both sexual and social was a theme of New York architect and author Chris Rawlins’ talk about the little known (till now) mid-century architect Horace Gifford. His amazing beach palaces dot several communities on Fire Island, a skinny barrier beach off Long Island.

It was a gay Mecca, and most of Gifford’s clients were gay men.

“I began knocking on doors and was regaled with alternately poetic and salacious tales of the young, handsome, and talented architect, who once had the run of this island, an eccentric and charismatic man whose business attire consisted of a briefcase and a Speedo,” said Rawlins, who wrote a book on the architect, ‘Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction.’

|

Rawlins found a range of phenomenal houses, hidden in trees along the sandy strand, or bisected by breezeways. One was “a house seemingly floating among the tree tops.” He called these “early ‘60s pavilions that provided refuge from a hostile world." Referring to the Stonewall protests in Greenwich Village that helped usher in gay lib, he called his later homes “exuberant post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS masterpieces that orchestrated bacchanals of liberation.”

“For this brave new world, Gifford invented an architecture of seduction,” Rawlins said. “Voyeuristic expanses of glass, outdoor showers, mirrored ceilings, prurient lines of sight, and sexy conversation pits. Horce Gifford conferred a benevolent order upon a culture in which all the old restraints were falling away.”

“His architecture traced the arc of gay liberation with uncanny precision.”

Not dissimilar were some of the designs of Paul Rudolph, an internationally known architect – but known more for his institutional work than for his quirky, sometimes kinky, residences.

Kelvin Dickinson, who heads the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation, titled his talk. “Paul Rudolph and the Search for Sensuous Space.”

He described Rudolph, the son of a minister, as creating homes that seemed to be designed for intimate encounters, focusing in his later career on “the sexuality of spaces, primarily bedroom and bathroom,” including bathroom walls covered with slivers of mirror to produce kaleidoscopic effects.

Rudolph home plans provided multiple levels and referred to rooms as the “fish bowl,” “the nest,” “the cave.”

Fashion designer Halston, who inhabited a Rudolph residence in New York City, turned it into an ultimate party house, with partygoers dancing from floating platforms. Liza Minnelli took a famous fall. “The house,” Dickinson said, “became a kind of bar.”

- ‹ previous

- 416 of 677

- next ›