Newcomer Rediscovers Neighborhood’s History

|

|

|

Karina Marshall is a relative newcomer to her Eichler neighborhood in San Jose and to Joe Eichler and his many modern tracts. “We’re new to California,” she says. “Eichlers are new to us.”

But thanks to deep curiosity and the commitment to follow through, Marshall has already produced more historical information about her subdivision than anyone ever knew.

The area was known only as Rose Glen, which takes in other neighborhoods beyond the Eichler tract. No one knew what the tract was called. It’s an early tract, from 1952 and 1953, so there were no oldtimers to recall the earliest days.

“There was not much information on neighborhood,” Marshall says, adding, “I just wanted to learn more.”

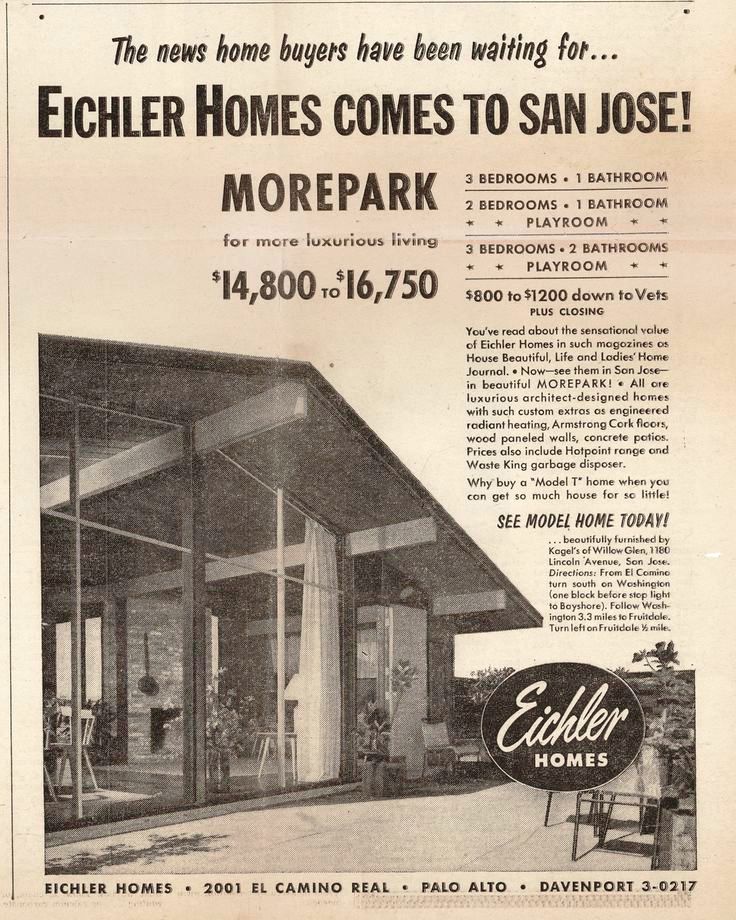

A little online sleuthing produced the first important historical artifact – the original name of the tract. She found an ad for “Morepark,” and the ad instructed would-be buyers how to find the model homes.

|

|

|

“If you followed the directions, it took us here,” Marshall says.

“This was the first time anybody in this subdivision knew we were called Morepark.”

The new but old name is starting to stick. “People are already starting to call it that,” she says.

But Marshall still wanted to know more. Her neighborhood, after all, is going through something of a revival, with people buying and fixing up homes and social events on the rise.

Yet, because the homes are early Eichlers, they are sometimes ignored by outsiders.

“We’d even heard from one of our contractor people these aren’t really Eichlers,” Marshall says, adding, “They are absolutely Eichlers, not a doubt.”

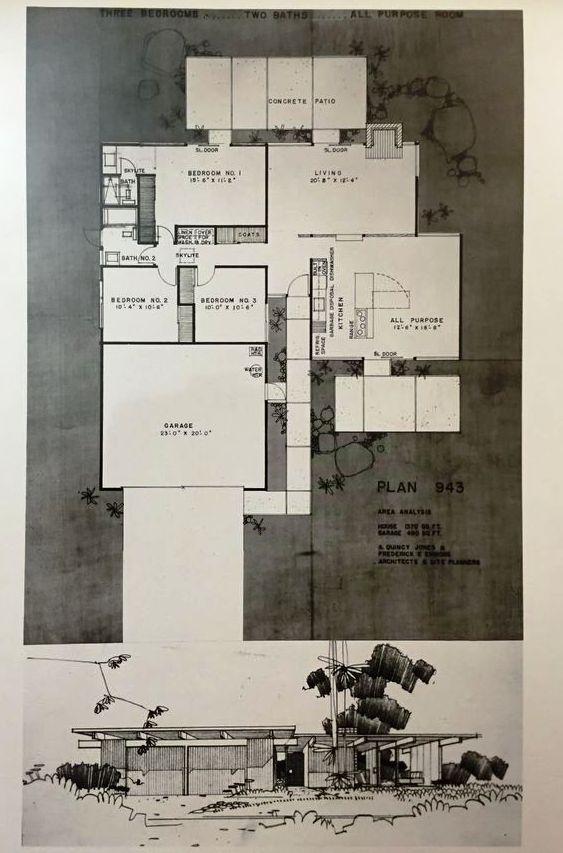

To further her research, while on a business trip South she visited the research library at UCLA to pore through the expansive archives of A. Quincy Jones whose firm, Jones & Emmons, was one of two architect teams to design homes for Morepark. The other was Anshen & Allen.

The firms generally designed homes on their own, though shared ideas, with one firm building on a concept originating from the other. But here, the collaboration was even closer.

“Many site plans for Morepark had both architects’ logos on them, which was kind of interesting too,” Marshall says.

“This was kind of an experimental neighborhood,” she says. “They had a survey done here, and in two other neighborhoods, including Maple Glen in Palo Alto, asking people how they liked their open floorplan kitchens and other features of the houses."

“It was great,” she says, about being in the archive – which is housed the Charles E. Young Research Library, which was designed by Quincy Jones.

|

|

|

“There was something really super about being in this room and holding the original paper, the original correspondence, Eichler asking to see plan 219, to see two copies. It felt like you were going back in time a little bit.”

One interesting tidbit she gleaned: one side of Richmond Avenue, the tract’s spine, had radiant heat pipes of copper, and one of galvanized steel.

Marshall also found correspondence between Eichler and an architectural writer who was critical of some aspects of Eichler’s work, in Morepark and elsewhere.

In a 1953 book, ‘Before You Buy a House,’ writer John Hancock Callender cited Morepark as an example “of the general excellence of the Eichler developments.”

But in his writing and in a letter to Joe Eichler, Callender said some homes were poorly oriented on their sites, and also criticized placement of kitchens and poor circulation, among other concerns.

“While we do not always achieve as good orientation as we like,” Eichler responded in a November 1952 letter, “we certainly do not disregard it and we try our best to give proper orientation within the limits allowed us.”

Eichler’s letter was copied to both teams of his architects.

Eichler agrees with some of Callender’s remarks about poor circulation, but says “these particular plans were experimental houses and were attempts on our part to produce houses that would sell for a lower price." Eichler says it proved impossible to reduce the sales prices of those homes and then goes on:

“Actually, these are very fine houses and are far superior to anything in this locality in that price range.”

|

|

|

The price range, by the way, was $9,400 to $15,000.

“All in all,” Eichler concludes, “I think that our current crop of houses is a tremendous improvement over what we have been doing for the past two years.”

He mentions selling some of the homes for $15,000 to $17,000 in Palo Alto, adding that “is too high for Morepark.”

“We are trying our damndest to get into a lower-priced field and still maintain our quality and supply most of the features that we do. We hope to be able to accomplish this in our next project.”

Marshall plans to catalog the material she photocopied and brought back from UCLA and perhaps write something about what she learned.

“It’s good to know the history of it,” she says of Morepark. “It’s the first San Jose neighborhood built by Eichler.”

- ‹ previous

- 440 of 677

- next ›