Why Joe Wouldn’t ‘Scrap the Architects’

|

|

|

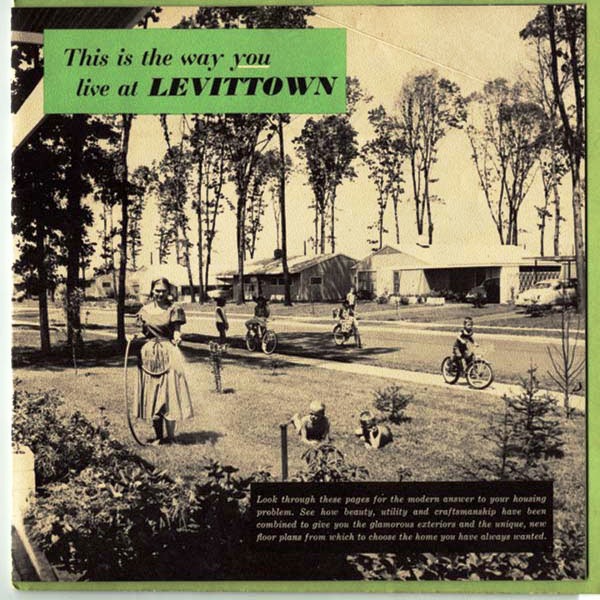

Throughout his career Joe Eichler enjoyed working with architects – and he worked with a lot of them. But in so doing he was breaking a homebuilding industry rule of the time, one that was forcefully stated at a 1952 convocation of homebuilders and architects by a leader of the biggest merchant building firm of all, Levitt & Sons.

“Scrap the architects,” Al Levitt told the gathering, which was held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At the gathering were such august figures as William Zeckendorf, Sr., a leading Manhattan developer, Walter Gropius, one of the inventors of modern architecture and founder of the Bauhaus, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

The event was tied to a convention of homebuilders from across the country.

“Our best hope is to scrap the architects,” Levitt said, “and get the live, alert, small, and large builders and give them some training, not more than a year.”

|

|

|

Albert Levitt, William Levitt’s brother, knew something about architecture too. Albert was largely responsible for designing the homes that filled Levittowns in Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey during the firm’s early years, and for laying out the developments.

Although the Cape Cod and Colonial-styled homes were nothing special architecturally, the planned communities often were, providing schools and parks convenient to homes, and curving, attractive roadways.

There is one significant way in which the Levitt organization was much less progressive than Eichler Homes. Levitt made it clear they would not sell to African-Americans.

By the late 1960s, Levitt had built about 140,000 homes – versus the roughly 11,000 built by Joe Eichler in his career.

It’s worth pausing to consider the variety of talented and strong-willed architects Eichler worked with during his career. There were his main design teams, Bob Anshen and Steve Allen, and A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons; also Claude Oakland and Oakland’s associate Kinji Imada.

|

|

|

Joe even had an in-house architect, John Boyd, who did some designing of Eichler homes and coordinated the work of other architects.

Then there were the architects Eichler brought in for specialized projects, like concrete highrises, or the special two-story home for Life magazine. These included Raphael Soriano, Pietro Belluschi, Tibor Fecskes, Aaron Green, Walter Brooks, Dan Liebermann, and others.

During the MOMA event, Al Levitt argued that it was would be wasteful and wrong-headed for large homebuilders to use architects, touching off what the magazine House and Home called “the liveliest debate of the convention.”

Levitt argued that the complexity of designs created by architects – he mentioned Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright as examples – was impossible to achieve in the mass building field.

Levitt also argued that the mass public would not buy modern homes in a mass way – an argument that has some truth.

|

|

|

How far will the public go in accepting modern, he wondered?

“Without even a trial balloon,” Levitt went on, “you guess in advance just how far you can push or persuade them to take either open planning or living in a fish bowl until the landscaping grows to give them privacy…”

Then Levitt got more personal – and here he got to the crux of why most big builders did not want to use architects.

Architects, after all, are simultaneously professional practitioners and artists, people who care as deeply about the product they turn out as homebuilders do.

Architects – serious architects at any rate – have agendas as well as homebuilders. They can present their case to the developer. They can persuade the developer. They can talk back.

Architect William Krisel, who with partner Dan Palmer, designed thousand of modern tract homes in the Los Angeles and Palm Springs areas, made this point recently in conversation with author Alan Hess.

|

|

|

The quote, explaining why most builders preferred to work with mere draftsmen and draftswomen as opposed to architects, comes from the recent ‘Williams Krisel’s Palm Springs: The Language of Modernism.'

“Hiring Modern architects involved complications that would cost time and money, whereas there were no arguments with a drafting service,” Krisel told Hess.

Here’s how Levitt put it in his talk:

"Probably the trouble with most architects is their gross impatience. They would like to see their dreams come true, but they don’t know how to attain them.”

While it’s not clear how many merchant builders, as they were called in the 1950s and 1960s, actually used architects to design their homes, it is clear that the number wasn’t high.

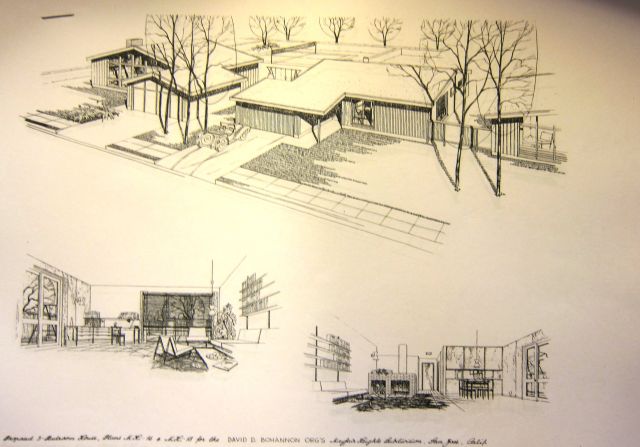

Also worth noting is this: even when developers brought in architects to design tract homes, they often did not carry out the designs as the architects intended them. Or, they leaned on architects who would have liked to produce truly modern homes to soften them, make them more traditional, make them an easier sell.

|

|

|

You can see this, for example, in tract home designs by Ed Fickett in Southern California, which were far less modern than his custom homes, or in Mogens Mogensen’s home designs in Northern California.

On paper, many of his designs are far more angular, glass-filled and abstract, than the actual homes that were later built.

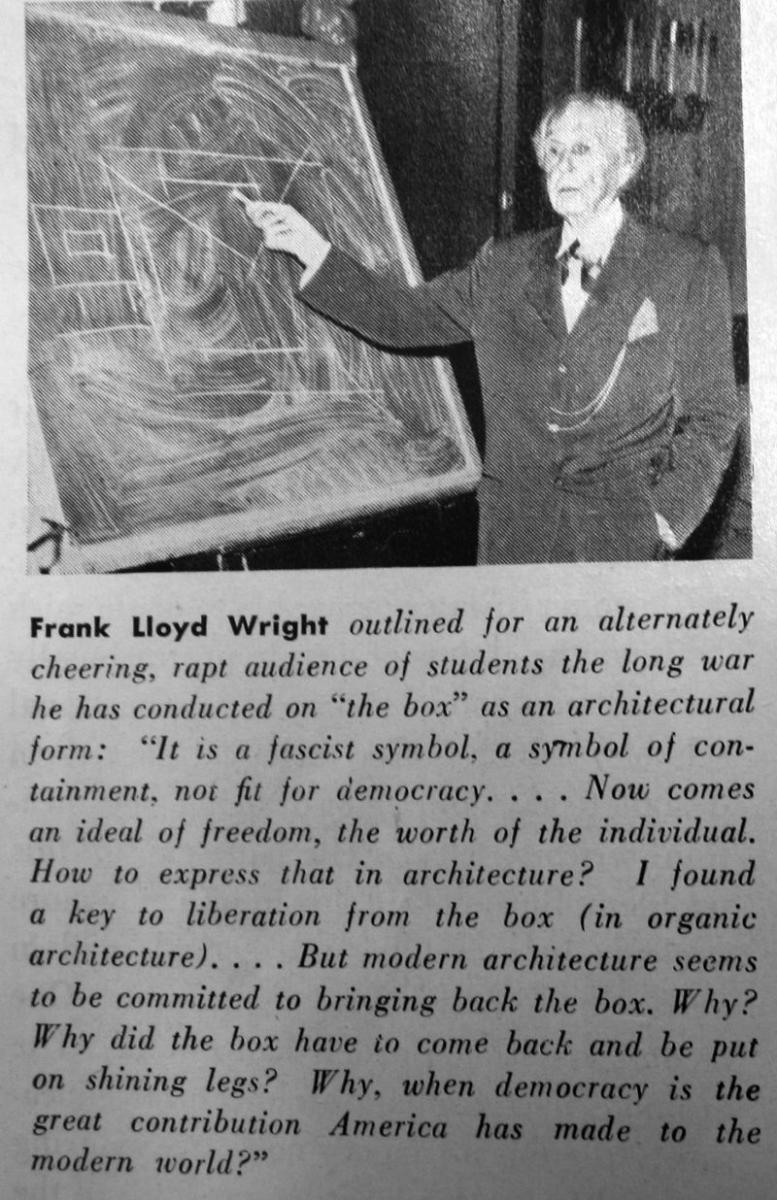

Wright himself spoke at the event – illustrating why a guy like Levitt wouldn’t have wanted to work with a strong-willed architect. Wright called “the box” – the sort of house companies like Levitt built – “a fascist symbol, a symbol of containment, not fit for democracy.”

Al Levitt made one interesting remark, answering a challenge from architect O’Neil Ford, who resented Levitt’s “very careless and slighting” remarks about Wright.

Levitt argued that the world would have been better off if Frank Lloyd Wright “had never thought of being another Leonardo” and had instead become a “speculative homebuilder.”

Wright might have been a lot like Joe Eichler.

- ‹ previous

- 652 of 677

- next ›