Architect Aaron Green - Page 3

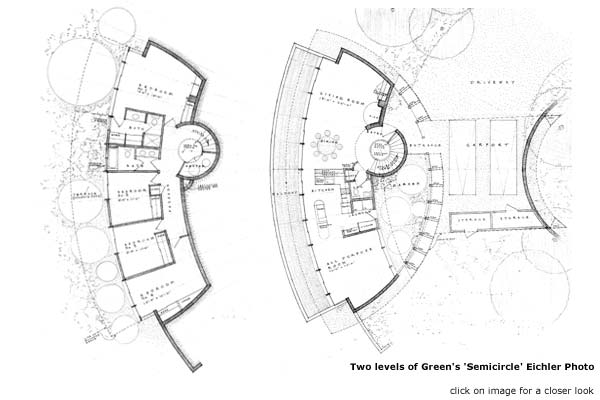

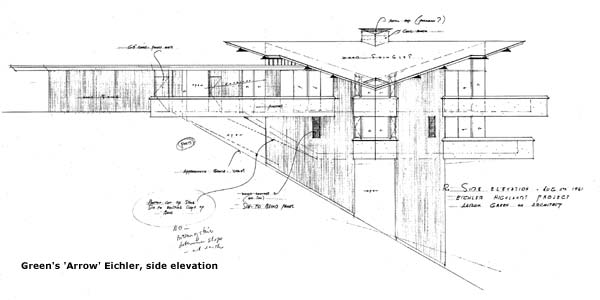

The Arrow was a bridge-like structure "out on stilts, a big platform," he says, "with a partial lower floor with bedrooms. The whole thing was a gable." "The principle grading involved the middle design," he says of the Semicircle, "which is the most dramatic one—which is sort of like my typical building. "Take a frying pan and saw the pan in half, you have half a pan and a handle. Make the handle into the carport. The half-a-pan is two stories, the lower half are the bedrooms, the living room was upstairs." The Arrow and Semicircle were two-story plans with open living areas above and bedrooms below. Both floors had radiant heat.

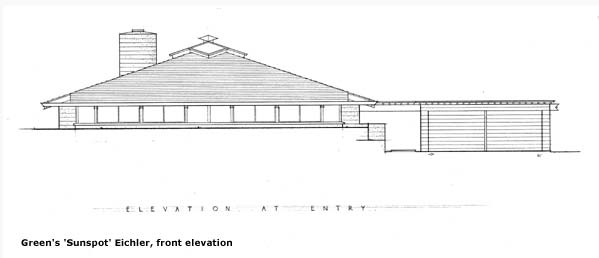

The third design, the Mischel-type Sunspot, was one-story. "It's a wonderful house," says Mark Granovetter, who has lived in the Mischel house on the Stanford campus for eight years with his wife Ellen and a daughter who recently moved out on her own. "It's a very easy house to live in." He loves the open plan, detailing, indirect lighting, and soaring ceiling. Ellen, who'd wanted more eastern light, had a small portion of an overhanging eave removed.

Mischel also loved the house, which he calls "wonderfully friendly," but did have a complaint—sounds carried everywhere, even into the bedrooms. He and his wife raised three children there and never had to wonder what they were up to. "If the kids are eating Cheerios or cornflakes—you know what the cereal is they're eating."

The house has two parts—a grand living area, and a line of bedrooms and utility rooms, up a few steps and separated from the living area by a decorative wooden screen. The living area is a single space incorporating a "living room" with fireplace and built-in shelves and seating and a wall of concrete brick; a kitchen-dining area complete with Eichler-type cabinets and freestanding range, and a half-hidden study area that gets the most use, Ellen says.

The wall of glass facing the pool and garden and beamed ceiling rising to the skylight are the dominant architectural features. Half-diamond shapes add interest throughout—as in a window above the entry door, on cabinetry shelves, by the master bedroom mirror. A small room behind this area was added to the original plan at Mischel's request. Throughout the house color is used subtly. Terra cotta strips complement the brown piers, and terra cotta brackets decorate the ends of the rafters.

Mischel, today a psychology professor at Columbia University in New York, recalls arriving at Stanford as a young professor with an interest in architecture but little money. Several of his neighbors lived in Eichlers on campus, customized from tract plans.

Mischel approached Eichler and was shown the Sunspot, which he was told was designed by Green as a model for the proposed subdivision. Mischel was impressed, even though the Green design would cost 25 or 30 percent more than a standard Eichler plan. Work started in the summer of 1962 and was complete by Christmas. It didn't go as smoothly as Eichler would have liked. Although both Eichler and Green visited the site regularly, Mischel says, he never saw both there at the same time. Green insisted on details that cannot be found in other Eichler homes, Mischel says, like mitered glass corners. The skylight turned out to be more expensive than anticipated, and the 19-foot ceiling beams difficult to install.

"Eichler came over and cursed about it," Mischel says. "He stood in the middle of the house smoking a cigar and used filthy language. 'You don't know how much this thing is costing me!' " Eichler didn't blame Aaron Green, Mischel says. "He blamed life. Part of it was Aaron's fault. He was such a perfectionist."

Mischel believes the high cost of the models convinced Eichler to drop the Highlands. Liebermann blames the slope. "I think they decided that they couldn't afford to develop a hillside site." Eichler was also turning his attention to the urban high-rise projects that would eventually bring financial trouble to his company. "We were all disappointed when Eichler decided not to do it," Liebermann says. "Had he been able to fund it and hold onto it, it would have been a goldmine."

Mischel acknowledges that he came out a winner. Instead of a model for a housing tract, he ended up living in a one-of-a-kind home designed by Aaron Green—and with a lot of history to boot.