Arts & Architecture: Magazine with a Mission - Page 3

"Modern has grown up at last," Richard Peferle wrote, as a sort of explanation. "It has passed through the transitional stage and achieved something really good in the matter of design, color, and texture."

"Most of us remember," he went on, "when modernism was considered on a par with the milder forms of insanity."

The advisory board grew increasingly modern as well: Grace Morley, director of the San Francisco Museum of Art; Dorothy Liebes, the textile designer; Harwell Harris; Frankl. By 1942, Charles and Ray Eames were associated with the magazine, designing an occasional cover and writing. Later came architects Henry Hill, Mario Corbett, Marcel Breuer, and Ain; landscape architect Garrett Eckbo; and designers Finn Juhl and George Nelson.

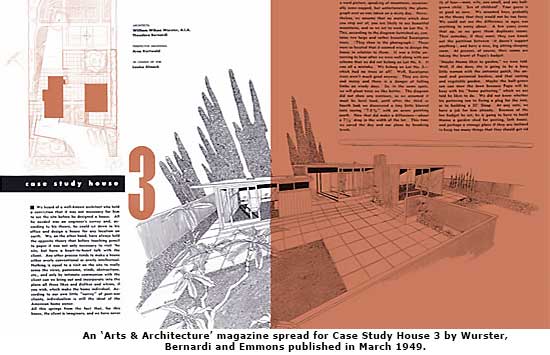

The look of the magazine also changed. Herbert Matter, a Swiss expatriate designer, photographer, and painter who had designed the Swiss pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair, remade the magazine according to his theory: "Visual excitement is created by tension." The result was often stripped down, angular; a mixture of photography with line; the frequent use of collage.

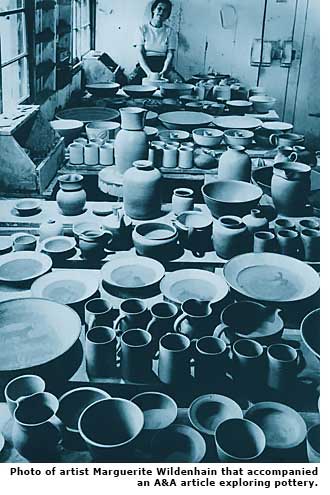

Alvin Lustig, John Follis, Isamu Noguchi, and many other designers—even Saul Bass—contributed to the magazine's look. Follis designed dozens of striking covers. Julius Shulman was listed as staff photographer—although, according to writer Esther McCoy, the only paid staffer was one assistant and contributors worked for gratis. "Every now and then we paid for a cover," Travers remembered. All the great architectural photographers contributed to the magazine, their work paid for by the architects: Morley Baer, Ernie Braun, Ron Partridge, and many more.

It's not clear what advisory board members did—other than contribute articles and photos of their work. But Entenza, a very hands-on manager, kept busy. Except for a few years during the Case Study period, when hundreds of thousands of people would visit each house once it was completed and open to the public, the magazine did not make money, Travers said.

'Arts & Architecture' strolled through the 1950s and '60s at 32 or 38 pages an issue—at a time when 'Architectural Forum,' published by 'Time' and aimed at the trade, hit 200 to 300 pages.

Entenza's advertisers were often manufacturers whose products figured in the houses published in the magazine. For Case Study houses, Entenza received discounted products in exchange for promotional consideration. "Craig Ellwood, designer, selected...21 aluminum sliding glass doors by Glide for Case Study House No. 17," one ad proclaimed.

But moneymaking was never Entenza's main goal. Born to wealth in Michigan (his family was in copper mining), he studied aesthetics at the University of Virginia and learned well. "He was acerbic, sarcastic, brilliant beyond intelligent, a fabulously cultured human being," said Stanley Tigerman, a Chicago architect and close friend. "But he didn't suffer fools gladly."

By the mid-1930s, besides writing plays, Entenza was working for MGM in the experimental film division. Fascinated by architecture, he used his wealth to purchase the magazine. "He loved being editor," Travers recalled, adding, "He was a benevolent dictator, but he had dictatorial material in him."

Entenza was proud of his Case Study program. "We like to think that these homes, over the years, have been responsible for some remarkably lucid thinking in terms of domestic architecture," he wrote. But by the mid-1960s, Travers said, Entenza realized that architect-designed homes would not have the impact on the American landscape that he had desired.

In 1962 Travers traded Entenza a piece of property for the magazine. Entenza had already moved to Chicago to run the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, doling out grants for exhibits on modern art and architecture.

Travers ran the magazine until 1967, upping circulation from 8,500 to 12,500 but not sufficiently boosting advertising. Money gushed out and backers couldn't be found. "I really cared," Travers said. "I really thought the magazine deserved to be there."

In Chicago, where Tigerman met him, Entenza enjoyed life in one of Mies van der Rohe's Lake Shore Drive Apartments ('Arts & Architecture' showed the building under construction back in 1952).

A voracious reader, Entenza devoured everything from silly novels to philosophical tomes, Tigerman said. Entenza, who was gay, also attended symphony and opera openings and black-tie fundraisers as "the consort, the walker, the escort to the richest society grand dames in Chicago. He was their perpetual date."