Beyond Flash and Fantasy - Page 3

The architect's second fertile period, from 1956 to 1963, explored what Olsberg calls the "poetry of poured concrete." Notable works included Silvertop (1956), with its amazing pair of reinforced concrete truss roofs.

Lautner's third great period, which Olsberg dates from 1968 to 1973, showed a "revolutionary fluidity in planning and shaping space."

The Elrod house (1968), designed for interior designer Arthur Elrod in Palm Springs, features a dome-like ceiling of reinforced concrete that floats apparently unaided above a circular seating area and a mountain of boulders that protrudes through the floor.

The rock outcroppings, which also serve as walls, originally sat below the home's designated pad. Lautner convinced Elrod to excavate the site so the home could be built among the rocks. "I decided we'd do something that really suited the desert," Lautner told Laskey, comparing the house to "a desert flower."

From the 1960s on, Olsberg writes, Lautner "pushed against so many barriers that (his works) were checkered by compromise or outright cancellation." But he had many successes.

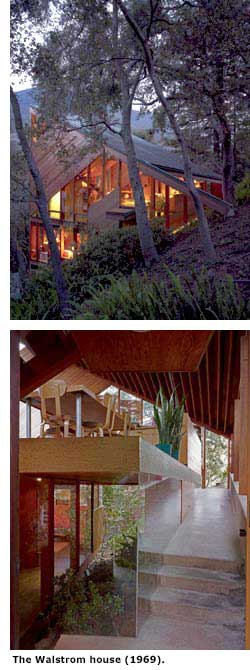

The Walstrom house, built in 1969 on a steep canyon slope shaded by oaks, is a woodsy throwback to Lautner's earlier work—and thus a good fit for its setting. Visitors reach the house by taking a walkway that switchbacks up the hill like a mountain trail, switchbacks again as it enters the house, and again as it ramps up into the living room.

The Walstrom house is all diagonals. The house itself is shaped like an arrow, as it floats over its site, anchored to the hill with steel girders. The wooden siding and cabinetry are angled, as is the loft that juts out over the living room. "From the carpentry to the cabinetry, every element follows the same logic," Escher said.

Architect Duncan Nicholson, who won a job with Lautner in 1989, after five years trying, found a man who was completely without airs but impressive nonetheless. "He was over six feet himself. He was big, broad," Nicholson said. "His hands were huge. He had a larger-than-life portrait of himself in the office behind him. It seemed like there were two of him in the office, as though one weren't enough."

Lautner was humorous and an enjoyable conversationalist. He'd take his staff to lunch at Musson & Frank, a legendary Hollywood eatery, and gave Christmas parties at his apartment two blocks from his Hollywood studio.

The apartment was filled with Lautner's collections, toys, a life-sized papier-mache Asian tiger with a wicked grin, paintings by his mother, books, and jazz records. Lautner enjoyed travel and photography, watched Michigan play football on TV, and after work would often stop by a local bar where his cronies, shoe salesmen, plumbers, "not architects, regular guys," would always have a seat for him, Nicholson remembers.

Ill with a form of neuropathy that restricted his movements, Lautner worked almost to the very end. "Thinking about architecture and solving problems, being creative and being original made him feel better," Nicholson said.

Early on, Nicholson ventured to ask Lautner, "How do you do it? Where does it come from?"

"He said when he was young, he didn't know if he could do it," Nicholson said. "It takes a lot of hard work, he said, a lot of perseverance. You know so much about building, and human experience. At a certain point it just begins to happen because you will it to."

Loving their Lautners

A John Lautner house may be a life-affirming place to live, but it can be tough to keep up.

"They're incredibly difficult to maintain," said John McIlwee, who lives in Lautner's Garcia house, a poem in poured concrete from 1962. "We have to re-scaffold the whole front of the house to fix a window because there's no way to reach it."

The good news, according to Ann Philbin, the Hammer Museum's director, is that most owners of the 45 or so Lautner homes in and around Los Angeles are "all very serious about owning these homes, and have the will, inclination, and resources to take care of them."

McIlwee and his partner, Bill Damaschke, are among the heroes who have restored their Lautner homes. Their house, with a roof that swoops to control strong sunlight, "was ruined when we bought it" in 2002, McIlwee said. "It's perfect now." The firm Marmol Radziner handled the renovation.

"The best thing we did," McIlwee said, "was live in the house a year before doing any work. Throughout the year, the sun has different positions, and with the glass and swooping roof, it changes the whole perspective."