Breaking the Rules - Page 2

|

|

|

|

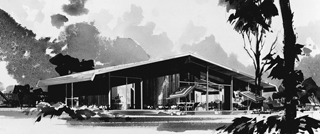

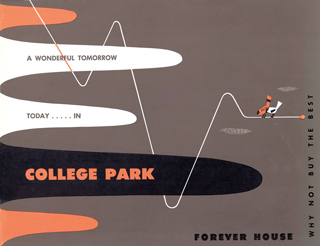

Jones' commitment to designing total communities lasted throughout his career, from his work as a lead designer for a cooperative housing community high in the hills of Brentwood in 1946, through schemes for clustered garden townhouses with butterfly roofs in Huntington Harbor and a city-within-a-city in Yucaipa, near San Bernardino, in the 1970s.

Many of the developments were never built, or never built as planned—including the remarkable plan for Yucaipa's Wildwood Ranch, with homes arrayed along a scenic highway. Plans called for additional greenways and park-like belts of trees flowing past clustered and single-family homes, and even a mini-neighborhood of mobile homes.

It's not clear why Wildwood Ranch was never developed according to the Jones plan. The demise of several of his other schemes is better understood.

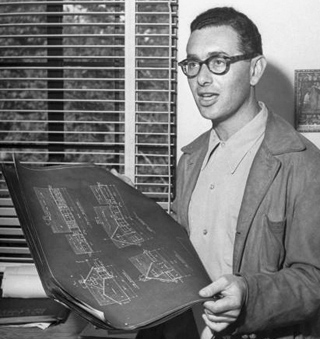

In the steep Brentwood hills, for example, where Jones headed up a team of architects and planners designing glassy, often angular homes for a group of Hollywood musicians, teachers, and writers who were organized as the Mutual Housing Association, the plan faced strong opposition from financiers and the government.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The original plan for Crestwood Hills called for 500 homes on 800 acres with cooperative schools, stores, transportation, and more. However, the hilly site and wide range of house designs pushed expenses beyond what was expected.

Banks hesitated to lend to a cooperative, a type of housing not favored by the Federal Housing Administration, and also shied away from Crestwood Hills because it was open to blacks and other minorities.

How daring a step it was to build an integrated community can be seen by comments by architect Vernon DeMars, a staunch progressive, who'd made his mark designing homes for farm workers in the 1930s. He faulted the members of the co-op for taking on one battle too many.

"Co-operatives have traditionally insisted on non-discrimination as to race, creed, and color, a rather academic consideration in England or Scandinavia, and one presenting no difficulties in running a consumer's grocery store in the United States," DeMars wrote in the February 1951 issue of Progressive Architecture. "Housing is something else again, and co-operatives should abandon not idealism but naiveté. Better housing is, in itself, a crusade—so is the cooperative way."

Although only 160 homes got built, and many since burned in a 1961 wildfire or have been demolished or remodeled out of existence, Crestwood Hills remains "one of the most significant postwar modern residential neighborhoods in Los Angeles," according to Ken Bernstein, manager of Los Angeles' Office of Historic Resources.

Jones & Emmons ran into governmental opposition ten years later to Eichler's most ambitious proposal for a planned community, in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Chatsworth. The plan called for houses to be set into the earth with berms, and greenbelts throughout the community.

"He couldn't get it through the L.A. city council," recalls John Gerard, an architect who'd worked for Jones & Emmons on the Eichler account. "One old man on the council referred to it as a communist design. They just flushed it down."

Also instructive is the story behind Jones & Emmons' unsuccessful struggle to convert the Levitt organization to modernism.