Breaking the Rules - Page 3

It illustrates the biggest hurdle progressive architects and planners had to fight through the 1950s and 1960s—hidebound thinking and rules on such things as setbacks and the arrangement of driveways and parking that made it impossible to cluster homes and provide adequate green space or optimal circulation.

|

|

|

For all its architectural conservatism, Levitt was one of the more progressive homebuilders in the country on planning issues. Levittowns had village greens and provided school sites and neighborhood shopping districts.

In the early 1950s the company even considered, but never built, a development called Landia that would have been a total community with homes, shopping centers, pools, and a town hall. An industrial zone supplying jobs would have been separated from homes by 'a shelter belt of trees.'

Alfred Levitt, one of the founder's sons, had a background in architecture and a strong interest in planning. He may have brought Jones & Emmons into the fold. Alfred Levitt had left the company, however, by the time work started on Pennypacker Park, part of Levittown, New Jersey.

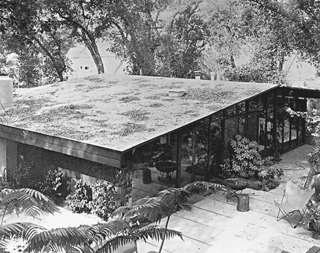

The architects' designs for these homes were as modern as anything they turned out for Eicher.

From the start, the 15,000-home subdivision on 6,000 acres of farmland was intended to include parks and school sites. As eventually built, the subdivision, today called Willingboro, features cul-de-sacs, routes heavy traffic away from neighborhoods, and includes 'conservation areas' that snake through the neighborhood.

|

|

|

|

But the Jones & Emmons plan went even further in several areas, grouping community center, shopping and a school, playground, pool, nursery, parking, picnic grounds, and pond in a freeform interior greenbelt.

Jones & Emmons also proposed varying how each house would be sited on its lot to create more usable and visually appealing spaces. "We would like to submit an alternate scheme for total lot use," Jones wrote in 1957 to Leonard Haeger, an architect and Levitt's technical director.

Jones understood there might be resistance. He said these "land development schemes" should be seen merely as concepts. "Naturally we would not expect that you would use this in the first eight sections of Pennypacker Park," he wrote, and suggested the ideas might be considered "for future use."

Instead, Haeger wrote back telling Jones to stick to standard setbacks and lot sizes. Jones obeyed. "We are living within the setback," Jones telegraphed.

Jones & Emmons' designs for the homes fared as poorly as their designs for the site. While Haeger professed that Levitt was "intrigued and delighted with the house designs," he said their one-floor plans and expensive materials would boost costs 25 to 30 percent.

By November, the Levitt deal was as good as dead. "It is really nice to receive the final payment," Jones wrote, "but our interest goes beyond just the financial end."

What, he wondered, would be happening with their designs?

"Chances are still excellent that we will build one of the several house designs experimentally," Haeger responded, "so that we can see the character of the house."

|

|

|

|

Did Levitt ever build one of Jones & Emmons' designs? Not likely.