Carter Sparks Magic - Page 2

"Carter wanted to know our philosophy," Franklin said. "He said anybody can design a home, can give you the amount of square footage and how many bedrooms you want. But he wants to know your philosophy of living." "He spent about a year just talking about what we wanted in a house," Sandra added. The result is a house that has many of Sparks' signature touches—but is also all about the Yees.

Like many of Sparks' houses, the Yee house is a bit off-putting from outside. With its redwood boards that have weathered to gray, the house suggests a barn.

There's the typical Sparks approach to the house—concrete aggregate pavers, more aggregate than concrete, leading to a rustic wooden deck without railings. But it's the door itself that shouts "Sparks." Solid redwood with faux paneling, it rises 12 feet to the roofline. A pleasant day could be spent touring Sparks' doors throughout the Sacramento Valley, each one different and dramatic. The doors, like something from a castle, tell you something about Sparks. If modern architecture had to avoid reference to past styles, then Sparks was no modernist.

In fact, Sparks' first plan called for the house to look like a pagoda, with three levels of roofline with upturned eaves. But the Yees scotched that plan, trimming the width of the eaves to save money, and eliminating the top roof to avoid offending the neighbors, who lived in single-story ranches. "He was thinking of it like a Chinese temple," Sandra says of Sparks. Playing up the couple's ethnic heritage was Sparks' idea; they hadn't suggested it.

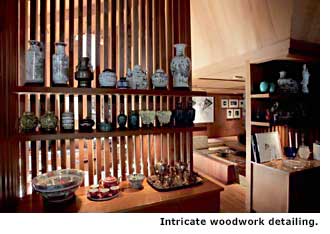

That was one of the few changes the Yees made in Sparks' plan, however. And many Asian touches remain, including chandeliers of Sparks' own design—a common Sparks touch. He even turned the George Washington columns into something Chinese. They support the ceiling beams in a way that can be seen in Chinese temples, Sandra says.

It became clear to the Yees that not only had they selected Sparks, he had selected them. He wouldn't work with anyone—just people he enjoyed socializing with. "He really did pick and choose his clients," Sandra says. "He picked the kind of client he could work with." Gregarious yet refined, Sparks loved skiing and socializing, Sandra remembers.

"With his custom clients, he would spend time getting to know them," said Jim Streng, one of the two Streng brothers. "Typically Carter and his wife would become friends with his clients—I mean close friends."

To Sparks, architecture was collaborative, even symbiotic, Franklin suggests. "He didn't like clients who wanted to run the show," Franklin says, "or those who said, 'You do everything.' He preferred clients who were engaged and took part in it. Then he rose to his heights."

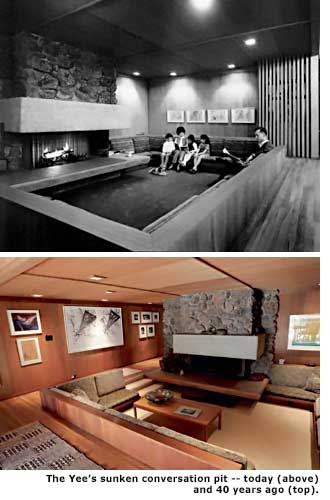

Sparks enjoyed rigorous geometry. The Yee house is symmetrical, essentially an octagon with the corners filled in by rectangular rooms. It is centered on a 34-foot-tall chimney. "It was really amazing he was able to do it without us sacrificing any function," Sandra says. "Because he was so artistic in nature," Franklin says, "I thought he would be impractical but, gee by golly, this house works."

The effect of the design is far from mathematical. The house resembles a rustic lodge. The entire living area, except for the children's rooms, is essentially one large room, like a tent. The master bedroom and library float above the main living areas, and look down on them through open balconies that can close up for privacy with sliding walls.

The natural stone fireplace is the home's dramatic and geometric center. Sparks suggested that the Yees water the stone to keep alive the moss that grew on it when it was installed. "I said, I don't think I'll have time to do that," Sandra recalls.

More even than most of his modernist colleagues, Sparks believed in the integrity of materials. The fireplace and adjoining wall are actually made of stone all the way through (with steel inside); the stone is not veneer. "To have architectural integrity, it has to be all stone, right through the wall," Sparks insisted.

"And he said, 'With most houses, the front of the house is finished, not the back of the house,'" Franklin says. "He wanted it finished all the way around, so every part of the house could have the front door."