Cold Cold Art

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first time Ethan Stern examined classic European 'cut' crystal goblets and fruit bowls and decanters, with their deeply etched lines and Rococo swirls, they offended his proto-modern sensibility.

He felt "repulsed," he has said.

Why then, some 20 years after this boyhood encounter at the Corning Museum of Glass, did Ethan buy a machine that is used to produce just such crystal?

Maybe he wanted to do something with art glass that no one else was doing.

Ethan, 40, is a young man in a young art form. Glass art may go back to Mesopotamia, but as a contemporary phenomenon its roots are in the mid-20th century American Midwest.

Ethan considers himself entrenched in a fifth generation of the American Studio Glass Movement, which allowed glass artists to create in a small studio, rather than a factory, thanks to the development of compact and affordable furnaces—and to the desire of glassmakers to emulate art potters.

"The Studio Glass Movement brought something new," Ethan says. "With factory glass, the people were blowers, but they were not the artists."

Young though it be, the Studio Glass Movement has grown big and busy, with schools specializing in glass art, glass art museums, and even a few commercial galleries that specialize in glass.

So an artist has to do something to make a mark. That's why Ethan imported a 1920s glass-cutting lathe from Vienna that had been used in a factory to produce commercial cut crystal.

Rather than focus on heroic 'hot work' glassblowing that most glassmakers specialize in, Ethan decided to go cold.

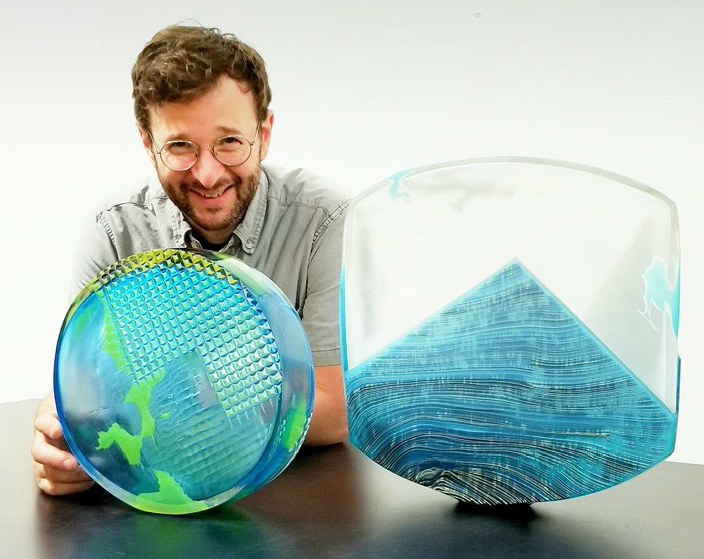

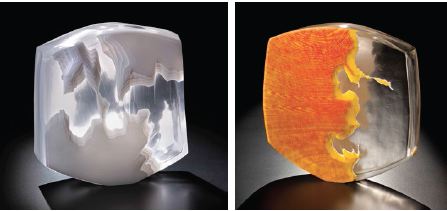

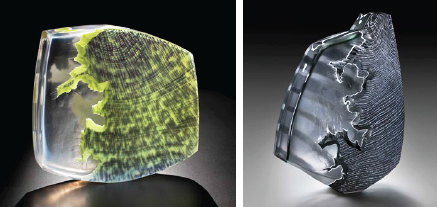

Yes, he blows glass, spending two to four hours in a hot shop on one of his typical pieces. He layers several colors of glass, one on top of the other, some with different opacities. But only after he leaves the hot shop does the real work begin.

Ethan dons goggles and earplugs, a thick apron, and respirator to protect against silica dust, hefts the glass object, and leans into his Viennese glasscutter. Whirrr! The cold work begins.

"I spend most of my time in the cold shop," he says, up to 40 hours per artwork. "In the cold shop I carve away layers of color." He adds, "It's like you're carving stone, removing material with the wheel or the grinder."

"Cold working, for me, is where I have created my voice," Ethan says.

It's also where's he's created his body. Glass is heavy. "I'd say my forearms are the strongest part of my body, just from holding the glass for cold working."

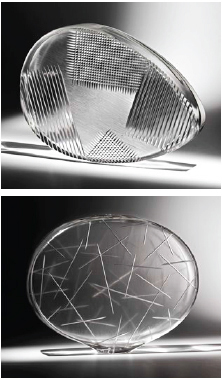

Ethan has been making a living with his art for years now. He makes tabletop sculptures that might suggest Antarctica seen from a blimp; or a flattened, over-sized, upright egg incised with lively Op Art-like arrangements of lines, swirls, and checkerboards.

He has taught glass art and was deputy director of the Pilchuck Glass School near Seattle. He assists other glass artists, and does glass work for non-glass artists who use glass as one component of their work.

Ethan is also something of a historian. He ponders about where glass is going, and what it can be in an age where artists are no longer tethered to their materials.

At a time when art is all about concept—or, increasingly, identity and politics—and not about the perfection of craft, what and how can artisans whose work is tied to a single material contribute?

Ethan thinks the answer is "plenty."

His art both plays up the inherent qualities of glass while at times subverting those qualities. Ethan began as a ceramicist, and says his early work resembled pots, with matte surfaces, rough surfaces, and "rich color that absorbs light."

Ethan says clay making still infuses his glassmaking. He wants people to see his hand in his work, as people can see the hand of the potter.