Craze Gone Crazy - Page 2

|

|

|

Everything old is new again

In 1940, Waldemar Kaempffert, the science editor for the New York Times, described the home of the future in which everything would be "molded, pressed, or fashioned out of an appropriate synthetic." If you don't believe that prediction came to pass, you haven't wandered the aisles of a Walmart or Target store lately.

In the era of the 1960s, homes and showrooms featured womb-shaped plastic chairs. Today those same styles are being mimicked in stores such as IKEA, West Elm, and CB2.

The classic curve of plastic Eames chairs began a flirtatious come-on and comeback with new consumers in the early 1990s. They were originally created by the husband-and-wife design team of Charles and Ray Eames in the mid-1950s and became even more popular in the decade that followed.

Plastic wasn't a new material in the 1960s. It had been around since the start of the century. Bakelite was a plastic that shouted 1930s. Yet, as the 1966 copy of the Ideal Home Householders Guide told us, "It has taken an unfairly long time for plastics to become visually sophisticated in color and design."

|

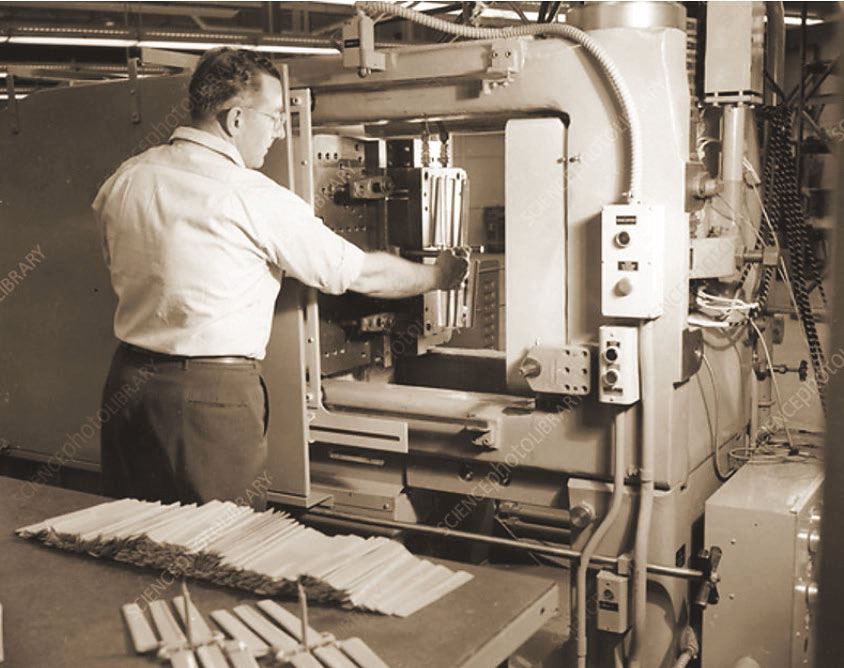

It took a while for plastic technology to develop, but soon enough varieties were created to flood the home with plastic products. Tupperware, for instance, an explosion of food containers, began its rise in the U.S. in the late 1940s, but it took until the 1960s for it to cross the Atlantic, reach the UK, and fill kitchen cabinets around the globe.

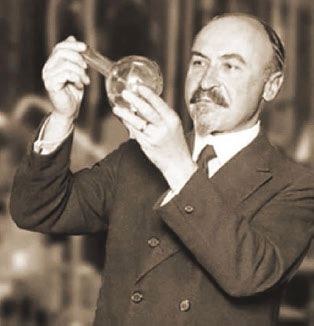

Leo Hendrik Baekeland may be the most important inventor you've never heard of. It was Baekeland who discovered the first synthetic plastic, in 1907. He was an unsung hero to modern chemistry and modern history.

Bakelite, named after its inventor, was one of the earliest synthetic materials, made from phenol and formaldehyde. At the time, it transformed modern life, used in everything from electronics to automobiles, cookware to jewelry, even billiard balls and toothbrushes. Bakelite seems to capture the feel and essence of the good ol' days. It feels hefty compared to today's plastics.

Eric Wrobbel is an LA-based collector of all things retro, with a special interest in small radios and television sets. His main focus is on mid-20th-century early transistor radios.

|

"Who didn't have that plastic rectangle with a sound hole plastered to their ear?" recalls Wrobbel. "It was our own portable entertainment center that we could take anywhere and everywhere."

When asked about the use of plastics for radios, Wrobbel replied, "It starts with brown Bakelite. This is thought to be the first widely used man-made plastic. It is the same stuff of which early electrical sockets and outlets were made.

"Bakelite is hard and durable, but only came in dark brown. To use Bakelite in consumer products like radios, manufacturers sometimes painted it [to attract customers]."

|

"There's a special warmth to older plastics like Bakelite that similar modern-day materials don't seem to convey, or add to the rooms they're displayed in," adds fellow radio collector Rich Ross.

"When you've been collecting for a while, these differences between modern and vintage materials become clearly noticeable. Older plastics develop a tangible patina that only adds to the enjoyment of owning them, while newer plastic seems flat and less of an art form in comparison."