Diamonds of the West

|

|

|

As the 1950s dawned on what was optimistically dubbed postwar America, there was no doubt who was batting cleanup for the newly crowned superpower.

New York was the big apple of Uncle Sam's eye, with a third more people than any other state, home to one out of every 11 Americans. New York was also the social, cultural, and financial capital of the nation.

But there was this fast-developing phenom on the West Coast—and New York's days on top were numbered.

California held promise in 1950, but barely more people than Pennsylvania and four million less than New York. The Golden State was still minor league—figuratively and literally. At a time when baseball was by far the preeminent American pastime, there had never been a major league team or game west of St. Louis.

Ever since getting called up to the big leagues by Americans and immigrants moving west by the millions, California not only assumed the population throne previously occupied by New York, but hit a cultural grand slam by bringing modern architecture to American tract homes—and major league baseball.

In leaving New York for California in 1958, recalls Venice-based architect Bob Bangham, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants "were making a statement that the new center of the universe was here [on the West Coast], not New York."

|

|

|

And in the decade to follow, five California cities joined the exclusive club with major league ballparks, achieving widely varied levels of success both athletic and aesthetic.

"I think it was an opportunity to try new architectural styles," says Janet Marie Smith, Los Angeles Dodgers vice-president of planning and development and the architect credited by many with saving baseball park architecture 30 years ago in Baltimore.

Since 2012, Smith has presided over the ongoing restoration and modernization of Dodger Stadium (1962), now the third-oldest park in Major League Baseball.

"That is what is amazing," marvels architect and author Alan Hess, preeminent historian of California architecture. Referencing Boston's Fenway Park (1912) and Chicago's Wrigley Field (1914), he adds, "We romanticize those so much as being part of the past, [and] now Dodger Stadium is in that league!"

The mid-century stadium in L.A.'s Chavez Ravine was not the first in California's major league career, however, as wonderfully told in the new book by a longtime architecture critic with (of course) the New Yorker, Paul Goldberger.

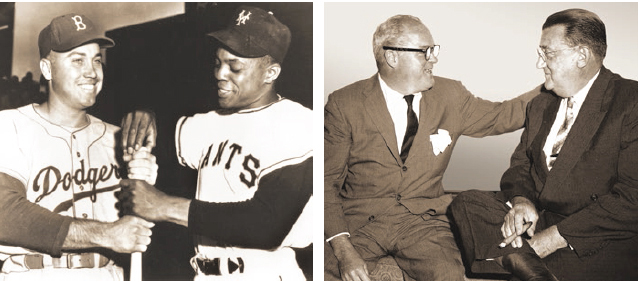

In New York folklore Walter O'Malley, greedy owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, had his eye on booming L.A. and dragged his longtime rival, the New York Giants, west with him to make California road trips feasible for National League teams.

|

|

|

Goldberger's Ballpark: Baseball in the American City (Alfred A. Knopf, 2019) tells a somewhat more interesting story, relating how both teams were unhappy in older ballparks, and the Giants toyed with moving to Minnesota before announcing San Francisco as their destination in August 1957.

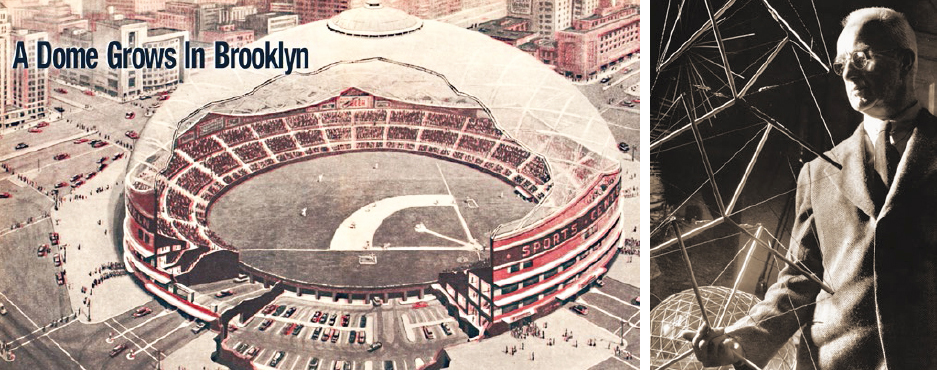

As recently as 1955, O'Malley had enlisted cutting-edge modern architects Norman Bel Geddes and Buckminster Fuller to design domed stadiums for two sites in Brooklyn, but facing 'intransigence' from New York redevelopment czar Robert Moses, he agreed in October of '57 to join the Giants' westward migration.

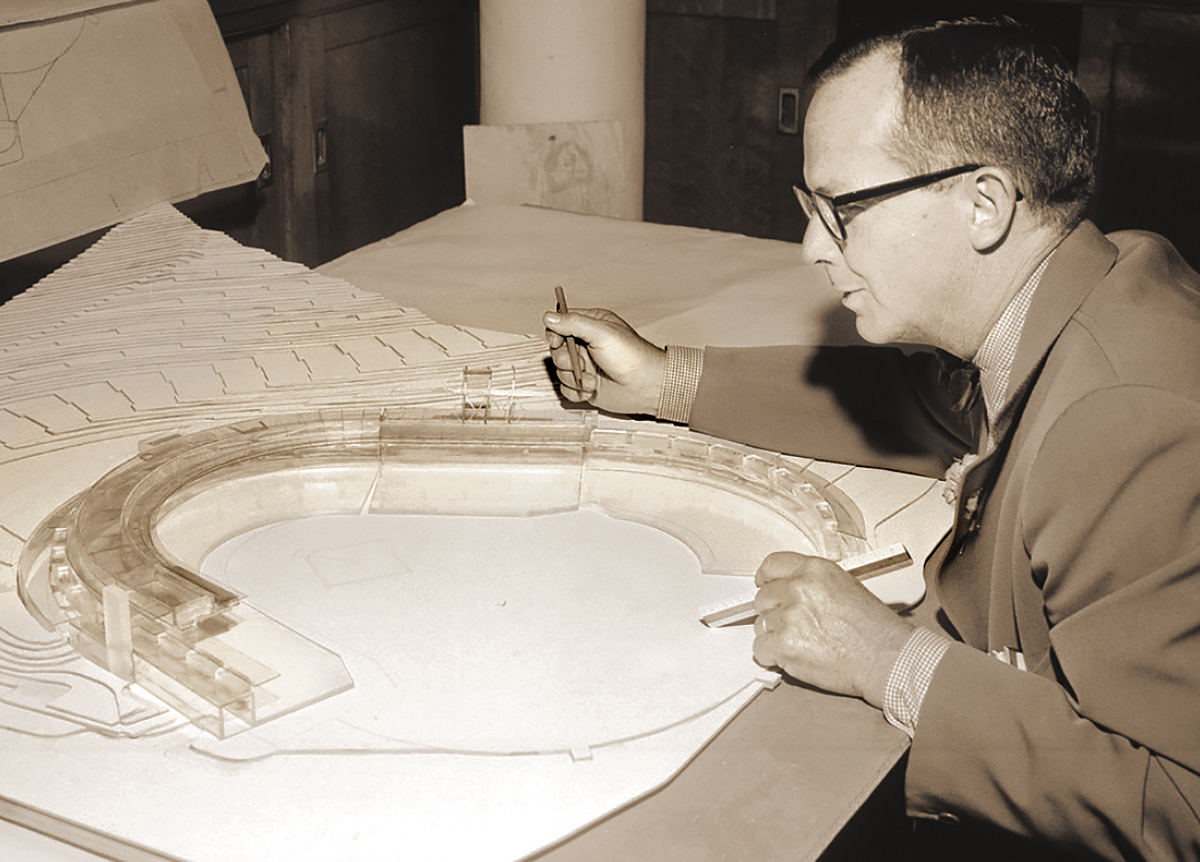

O'Malley and the city of San Francisco's ballpark developer respectively hired New Jersey-based engineer Emil Praeger and Bay Area architect John Savage Bolles to design California's architectural foray into the big leagues. For the first few years, the Giants played in what Goldberger terms the "vaguely Art Moderne" Seals Stadium (1931), and the Dodgers won the '59 World Series with their Brooklyn players in enormous Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (1923).

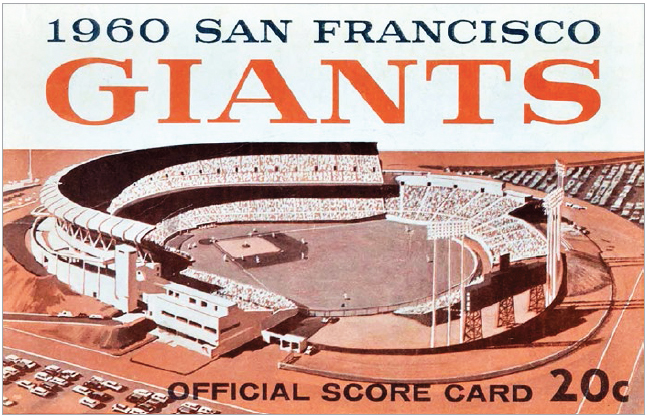

Bolles and builder Charles Harney finished their job first, and the democratically named Candlestick Park opened in April 1960 with a Giants win over St. Louis. Still, Candlestick seemed doomed—and Dodger Stadium blessed—from the start.

"The portion of the [San Francisco] site chosen for the ballpark was damp, foggy, and turned out to be susceptible to gusts of wind coming off the bay," writes Goldberger. He notes that its radiant heating system never worked right and adds parenthetically, "The initial wind test turned out to have been done in the morning, when winds off the bay are generally mild."

There's no disputing, though, that the 'Stick started a 1960s California craze, followed quickly by Dodger Stadium (1962), Anaheim's Big A (1966), San Diego's frequently renamed multiuse stadium (1967), and Oakland Coliseum (1968).

|

|