Downtown in Style - Page 4

|

Fashions varied through the 1950s, often making use of new, synthetic materials that provided for easier care and greater comfort. Thanks to the 'Fabric Revolution,' casual clothes were wash-and-wear.

Throughout the '60s fashions evolved, and some thought devolved, with dresses, gowns, and women's suits inspired by Asia featuring "opulent brocades," with "simple silhouettes in exotic colors." Bonnie Cashin supplied "a Noh-cut coat with a big hooded collar, inspired by wraps worn by Japanese Noh dancers."

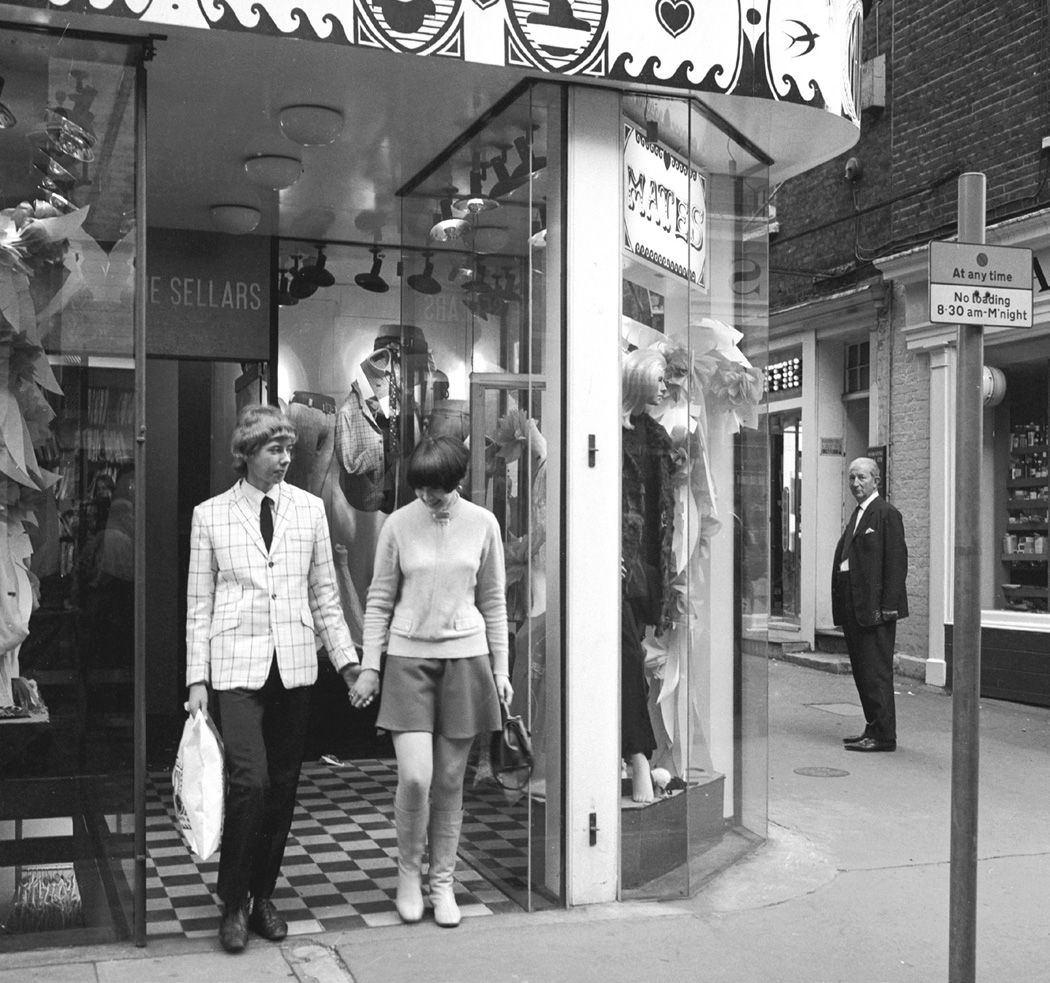

Designers for small boutiques in London's Carnaby Street pioneered more affordable looks that attracted young buyers—and others too, challenging the rule of more conservative haute couturiers.

Mary Quant, who her London boutique in 1955, bragged that, "in our shop you will find duchesses jostling with typists to buy the same dress."

|

Pants were fine for high fashion by 1960, the Chronicle's Evelyn Hannay reported. "This most recent rash of trousers for town actually broke out some time ago, but is becoming more contagious as one designer after another catches it."

By 1961 Rudy Gernreich's couture in denim was on the racks at Joseph Magnin. Two years later, with women following Jackie Kennedy by wearing pillbox hats, Hannay spoke to the wide choice women had, whether for daytime wear or evening. "There is no one look to which all women must bow down," she wrote.

Some couturiers began to focus less on one-of-a-kind garments for the wealthy and more on ready-to-wear lines for the well-heeled masses.

As the Chronicle's fashion writer Joan Chatfield-Taylor wrote in 1968 about Yves Saint Laurent: "His couture collection is now more of a laboratory for new ideas," she wrote, to be used for less-pricey garb. No longer, Chatfield-Taylor wrote, was the business of the Paris designer "simply making clothes for the few thousand women in the world willing to spend the time and the money for the most beautiful custom-made clothes available."

Whether to show a woman's knee and how much leg to show has always been an issue. By the mid-1960s the upstart designers had won.

|

When Norman Norrell showed his spring 1967 collection, Gertrude Doane concluded, "The smartly dressed woman can no longer protest it isn't ladylike to show her knees, because that's nonsense."

Hannay wrote: "Minidresses? At a Norrell show? Yes indeed. Norrell proved that anything Carnaby Street can do, he can do better."

"Needless to say," she added, "audiences at his showings have been absolutely scandalized."

Couturiers borrowed not just from Carnaby Street but also from San Francisco. Wild silk printed dresses that exploded in 1967 were inspired by psychedelic posters.

"It's not hard to figure out how the current popularity of fringe develop. You can thank our friends, the hippies," Chatfield-Taylor observed in 1968.

Meanwhile, what some called the 'costume look' allowed women to use designs from different locales, subcultures, and eras for self-expression. Under the headline 'Clothes to Blow Your Mind,' Chatfield-Taylor wrote, "Does she feel like a gypsy? She can dress like one. Does she want to present herself as an independent, freethinking type with a taste for the exotic? Let her."

|

Chatfield-Taylor called it the "look at me—the real me" look.

There was another real-me event in 1968: when the group New York Radical Women took over the Atlantic City Boardwalk in front of the Miss America pageant to protest judging women on beauty rather than brains. Into their 'freedom trash can' went cosmetics, bras, and fashion magazines.

As the wild decade closed, Gertrude Doane took time to consider what fashion means for real women.

"I believe in understated clothing," she told the Chronicle. "I wouldn't want anyone to notice what I wore when I entered the room—but that I had entered the room."

Photography & illustrations: Ernie Braun, Mark Shaw, Ray Roberts, W. David Shaw; and courtesy I. Magnin & Co. Records (San Francisco History Center - San Francisco Public Library), Joseph Magnin Co., San Francisco Chronicle, Popperfoto, Mark Hopkins Hotel, Heather David, Rico Tee Archive

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4