Dreamscapes of Elegance - Page 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

"I don't know how he came up with those ideas," she says of her dad's fantastic dreamscapes. "He used photos for his paintings and would have models pose. He would combine a photo of a sailboat and a person and a dog, and people dancing."

"For one Motorola ad, there's an image of a woman peering through these bushes. That was a photo of my mom peering through bushes," she says.

Borgman says Schridde's Motorola ads were admired. "His mind started going [putting his imagination into overdrive]. He was pretty enthusiastic about it," Borgman says.

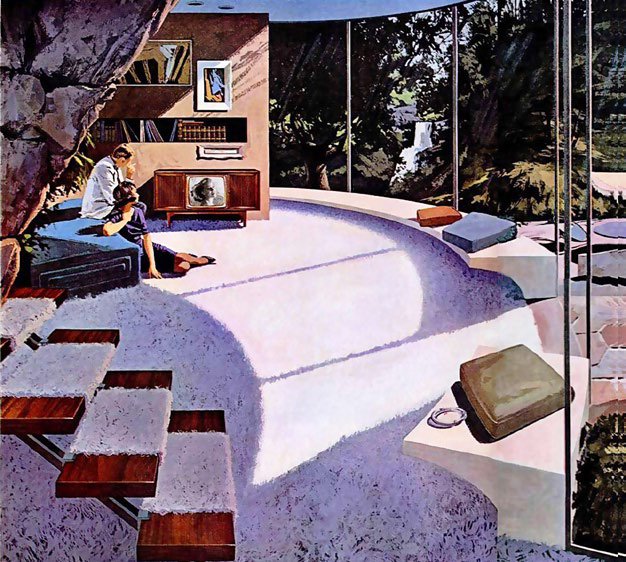

"As an illustrator one gets quite a variety of assignments," Borgman says. "An illustrator must always do some research. I'm sure that Charlie looked through architectural books and magazines for ideas.

"The art director probably asked him to do several idea sketches which would be shown to the client. They would pick out sketches that they liked and ask Charlie to develop them further. Charlie was a pretty creative guy, and I'm certain that a lot of the designs were his own. And as for the actions in the houses, they would be Charlie's ideas."

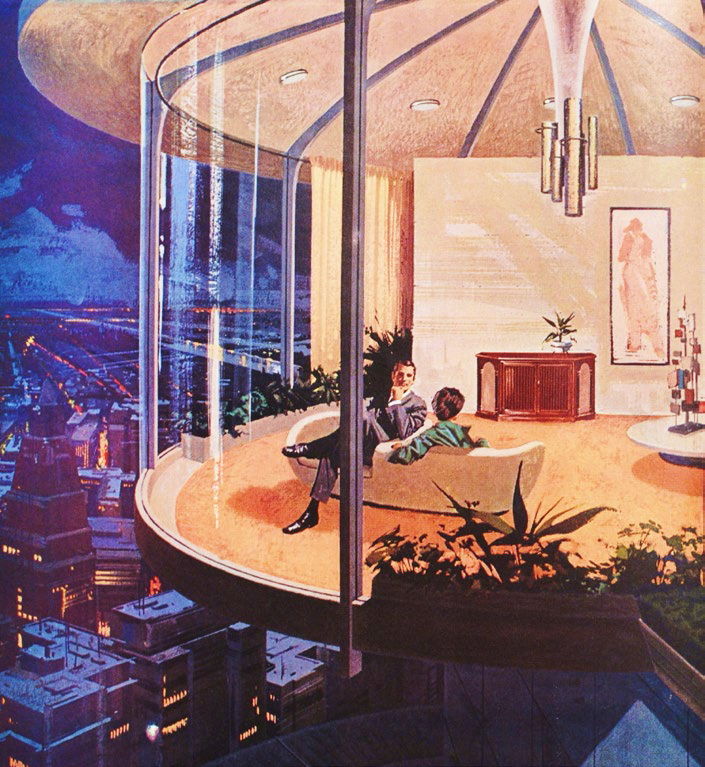

The text for the ads even made reference to Schridde's drawings.

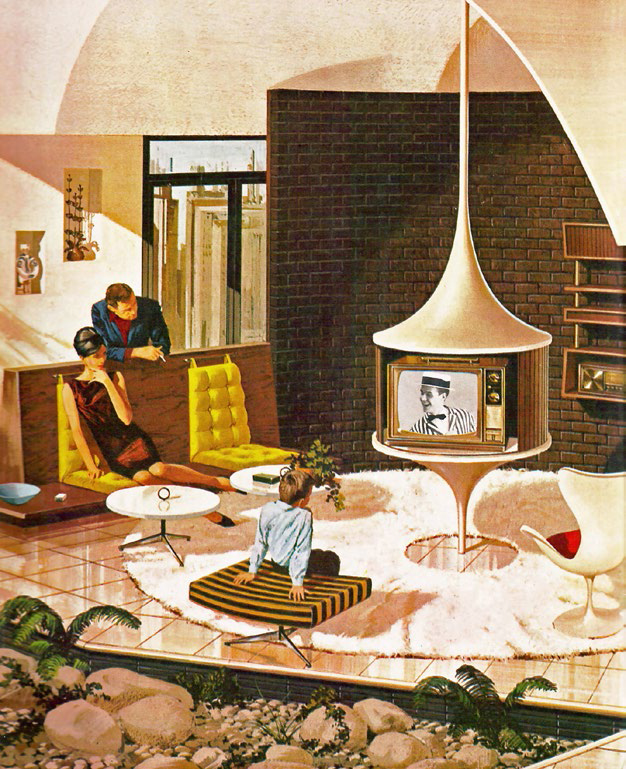

"This modern high-rise dwelling makes it possible to 'get away' from the city without leaving it," read the copy in an ad for a 'Dynamic Sound Focus' hi-fi. "Curved glass window wall forms a panoramic view of the city and surrounding countryside. Reflecting pool and shrubbery add warmth to ultramodern room setting, accented by dome ceiling."

As the 1960s ended, carmakers were turning from hand-drawn illustrations to photos for their ads and catalogs. Unlike some illustrators, who lost jobs, Schridde switched from pen and pencil to photography.

An engaging guy, Schridde enjoyed chatting with some of the stars he photographed for the auto companies—legendary pilot Chuck Yeager, auto racer Dale Earnhard, engineer John DeLorean, and actor Robert Redford.

Melanie remembers that her father was obsessed with one topic—art. He worked at it hard, and worked at it most of the time. "He lived and breathed art. That's all he wanted to talk about," Melanie says.

She recalls going to museums with her father and just sitting before paintings. He loved Maxfield Parrish, Edward Hopper, Botticelli, Rubens, Dali, "the Dutch artists," Egon Schiele, Klimt, Van Gogh, Monet, Manet.

"He grew up during the Depression. That's why he was focused on money and selling things. He didn't want to live the way he did as a child," Melanie says.

"I went with him when he was in his 80s to a reunion of his elementary school," she says. "A woman told me he did a wood etching of Sleepy from [Snow White and] 'the Seven Dwarves' and sold it to her for ten cents. He wanted his art to produce a livelihood, a living for him. And he did. He was around [age] ten."

In the mid-1990s Schridde remade himself again, this time as a fine artist focusing on Western themes, cowboys, mountain men, landscapes. He continued to take photos, many as source material for paintings.

Melanie says he would attend rodeos, taking dozens of photos, and then used the photos as bases for his paintings. Schridde, who'd spent his early years growing up on a farm in rural Illinois, had always loved the outdoors, she says.

There's even a book on these later career paintings, now collectable—Charles Schridde, Western Impressionism.

In 1993 Schridde moved to Laguna Beach in Southern California, where he met his second wife at, where else, the Laguna Beach Art Museum. For a couple of years they lived in South Africa, where Charles painted and photographed people, animals, and landscape.

"Excuse my language," Melanie says. "He had balls."

"He was on a safari, and they were all told not to stand up, not to disturb the elephants," she says. "My dad stood up. He did that so the elephant would charge. He got an amazing photograph of a charging bull."

By 2006 Schridde was living in a special retirement home—one devoted to, what else, the arts. The Burbank Senior Artists Colony was special enough that the New York Times profiled the place as "the country's first apartment community for creative older people."

"This is a place," reporter Patricia Leigh Brown wrote, "where amateurs discovering their inner Picassos in retirement can commune with working pros like Charlie Schridde, a painter in his 70s from the 'cowboy impressionist' school who resembles the grizzled trappers of his canvases."