East Meets West: Asian Aesthetic - Page 3

"The Japanese system was quite modular, and so was the modern movement that gave rise to the Eichlers," said Carroll Rankin, an architect who has lived in Eichler homes for 45 years. "The spacing of the beams is directly related to the span capability of the decking. It's a structural reason. There's nothing arbitrary in the Japanese or the Eichler home."

A. Quincy Jones, a leading Southern California modernist who was one of Eichler's leading architects grew up with a taste of Japanese culture, said his widow Elaine Sewall Jones, thanks to his friendship with Japanese neighbors in Southern California. Claude Oakland never made it to Japan, but was always interested in Japanese art. His sister worked in Japan with the Occupation, and returned home with a marvelous collection of prints. Oakland had some in his home.

Jones and his partner Frederick Emmons also acknowledged the parallels. In their 1957 book, 'Builders Homes for Better Living,' they expressed the Eichler philosophy of homebuilding, hoping the book would inspire other developers. Jones and Emmons used historic images of Japanese homes to illustrate yard use, privacy, and "a physical and visual extension of entry."

Other similarities between Japanese architecture and California modernism are striking. Both use posts and beams, with non-load bearing walls. The structure of the home is both revealed and reveled in, creating rhythmic patterns of woodwork, paneling, openings and light. The home is a series of linked spaces, not a box with compartments.

Traditional Chinese architecture too shares many of these characteristics. The planning was open and flexible, gardens natural and poetic. Rooms often surround an atrium-like courtyard, especially in larger homes that are complexes of related buildings.

Bo Bi, a Chinese architect who has visited the United States many times, says his first visit to Eichler homes reminded him of traditional Chinese 'Siheyuan' homes—a courtyard surrounded on four sides by rooms. ('Si' means four, 'yuan' means yard.). The goal was privacy in a crowded environment. "When I first discovered Eichler homes, I felt like I was in a mini Siheyuan," he said. "Even though the architecture and scales are not the same, the concept of having rooms arranged around a central courtyard is the same."

Similar courtyards can be found in many houses designed by the Southern California designer Cliff May, who often oriented his living spaces around a U-shaped courtyard. His inspiration was Spanish Colonial, not Asian, but the effect is similar.

Many of Palm Springs' modern houses, including those by the Alexanders, achieve similar privacy and outdoor living. People live in their outdoor rooms, sitting by the pool during the day and the fire pit at night, surrounded by walls that screen out their neighbors and provide instead views of the distant hills.

One parallel between Japanese and California modern architecture is an emphasis on rustic simplicity. Much of what we think of today as the 'Japanese home' evolved from the 16th Century Sukiya style. Sukiya, which means abode of refinement," used rough-hewn wood but elegant detailing to produce what Kazuo Nishi and Kazuo Hozumi, authors of 'What is Japanese Architecture?' call "unimpeded relaxation in the midst of nature." How very Californian.

Several modern California architects designed houses that resemble Japanese houses. In Northern California, some of Gardner Dailey's houses from the '40s and '50s took on an explicitly Japanese look, and John Hans Ostwald designed several Japanese-style pavilion houses in the 1950s and '60s. In Southern California, Harwell Harris's Japanese influence can be seen in the 1933 Lowe house in Altadena, with sliding shoji screens.

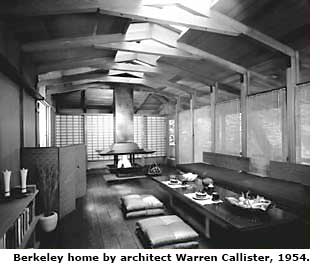

To find American architecture that pays as much attention as Japan to expressive woodwork and a dominating roof, you can look at bungalow builders Greene and Greene of Pasadena, or such later, Northern California architects as Jack Hillmer or Warren Callister. Several of Callister's homes from the 1960s to the '90s show explicit Japanese influence, with shoji-style screens and 'tokonoma' nooks for the display of art objects.

It's not by chance that American artists began turning to Japan in the 1950s. Several popular books, including Norman F. Carver's 1955 book-length photo essay, "Form and Space of Japanese Architecture," were spreading the word.