Echoes of 'Little Boxes'

|

|

|

If a nursery rhyme and a political folk song had a baby, it would be called 'Little Boxes.'

When that catchy anti-suburb tune hit the Bay Area airwaves in the early 1960s, we assumed they were singing about our neighborhood—Eichler's Fairglen tract in San Jose.

Except for variations in exterior door colors and beams, the houses in our neighborhood looked virtually the same with a minor exception: one style had a tent-like roofline, the other was flat as a flapjack. They all had glass and mahogany walls and a kitchen like the Jetsons.

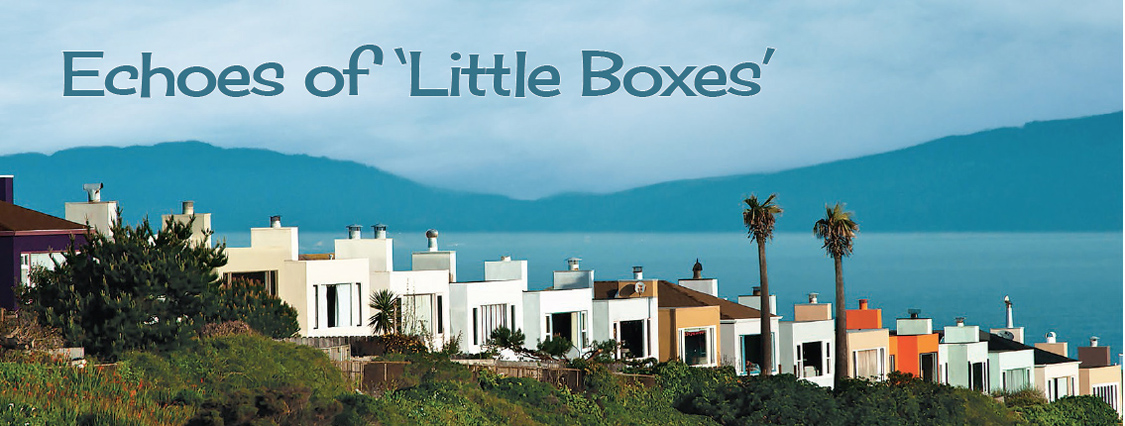

But when our family would drive north back then, past Daly City's Westlake development on the way to San Francisco, it was hard to miss the strings of seemingly identical homes covering the hillside like a rainbow of dominoes.

|

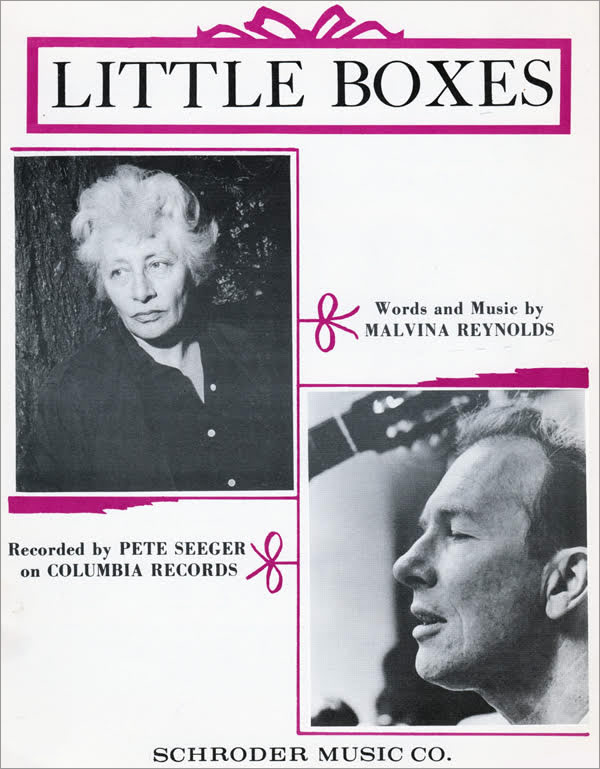

Those rows of repetitive architecture were the inspiration for Berkeley alumna and political activist Malvina Reynolds, who, back in 1962, scribbled down lyrics as she and her husband drove by that imposing landscape.

A year later her song 'Little Boxes' became a hit for Reynolds' friend, folk singer and fellow activist Pete Seeger, whose version is the one most people remember today.

What better time than now—on the 60th anniversary of 'Little Boxes'—to take a fresh look at Reynolds' lyrics and realize, with some surprise, how little has changed over the past six decades.

"Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky-tacky

…Little boxes all the same."

|

Like other folk songs of the era, 'Little Boxes' was a catalyst for cultural introspection and change. The song became so popular that the term 'ticky-tacky' cemented its place as a catchphrase for many years afterwards.

It referred to the shoddy materials sometimes used during the construction of mass-produced suburban housing during the 'Baby Boomer' years.

But while there was a lot of criticism about the sameness of the architecture of Westlake, the homes there were not actually made out of ticky-tacky and lesser materials. In fact, they were considered high-quality housing, and from close up, they didn't all look the same. Not at all.

The homes of Westlake were made out of redwood, with a variety of floor plans—as many as twelve. They contained high-end finishes, and all the front facades and colors differed.

|

However, the houses there certainly looked like an endless procession of side-by-side boxes with similar sizes, styles, and shapes—at least from a distance.