Fierceness Within - Page 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

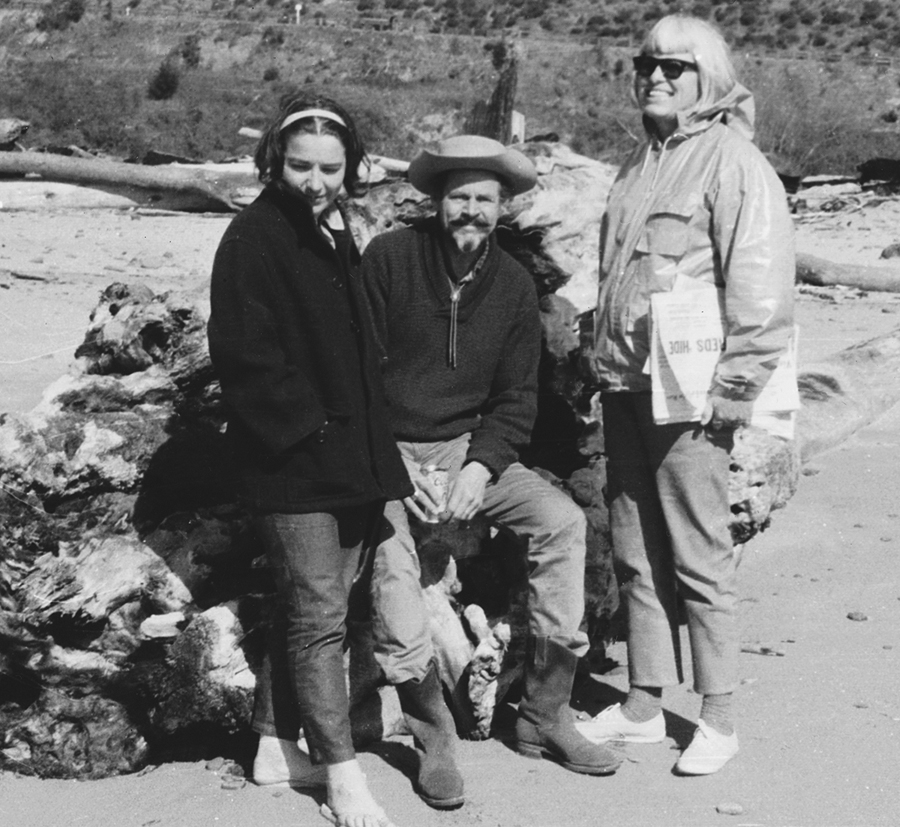

More even than the parties, it was the mountain itself that entranced Mac and Mary. While their parcel is only two acres, the adjacent land is protected open space. It's an environment they wouldn't have enjoyed in the Big Apple.

"How artists live in New York is not good," Mary says, recalling the early 1970s when she was there interviewing former California artists who'd moved there to advance their careers. In six months only once did she go to a gathering in an apartment—the rest of the time it was bars—because no one could afford a place large enough.

And the artists who did make it? Well, they had to sacrifice much.

"In the high echelons of the art world the pressure that is on them is incredible," she says, adding, "to be the star or something, to be something they don't want to be."

Part of Mary Fuller's success, maybe the largest part, is that she's happy to be who she is and unafraid to let anyone know it.

"It's great the way that she talks," says a friend, Sherri Hewitt. "Anything that comes to her mind, she says. She doesn't have a filter."

"She's a challenge in her conversational style when she's feeling a little persnickety," longtime friend Linda High says of Mary, especially if visitors "say something politically conservative, or anti-feminist, or stupid environmentally. That's a good way to get in trouble."

Life on the mountain was never easy. Although his career started out strongly in the 1950s, and his paintings entered museum collections, Mac McChesney never prospered as an artist.

"He was a major artist, but because of his refusal to move to New York, his prickly personality and robustly Stalinist politics, his heavy drinking, and the fact that there were no galleries in San Francisco, he got overlooked," his art dealer, Dennis Calabi, told the local paper The Bohemian in 2008, meaning that San Francisco did not have a vibrant art market.

"And they were too political," Linda High says of the McChesneys. "They didn't fit in. They just didn't play the game."

"She's one of those women who sublimated their energies to support her husband's art," Linda High says. "Her art got pushed to the side. Then she made her public works. That's how they made their money, because Mac didn't make much. Mac used to laugh and say that he had the largest collection of Macs in the world, because he sold so few."

As the main breadwinner of the family (she and Mac never had children), Mary conducted oral histories of artists for the Smithsonian Institute's Archives of American Art, wrote art reviews and other art articles from the 1950s through the '70s for a host of magazines, and was a staff writer and editor for a magazine.

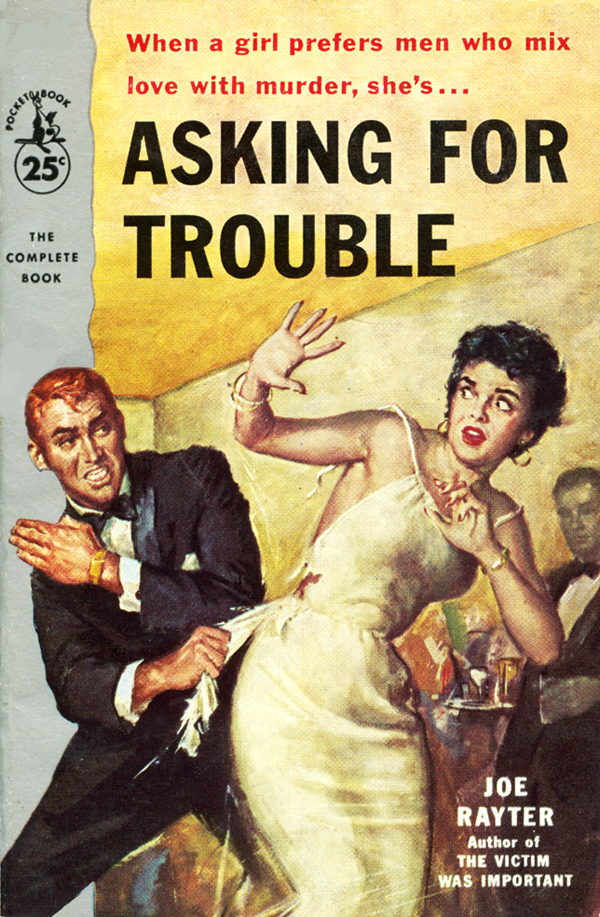

And, disguised as 'Joe Rayter,' she wrote a handful of mystery novels in the early 1950s that did well, the first earning her $3,000. "I thought, 'Wow, this is a lot.' I mean, the house in Point Richmond [where she had been living with her boyfriend and ceramics partner] only cost $9,000. So, $3,000—hey, I'm rich, you know."

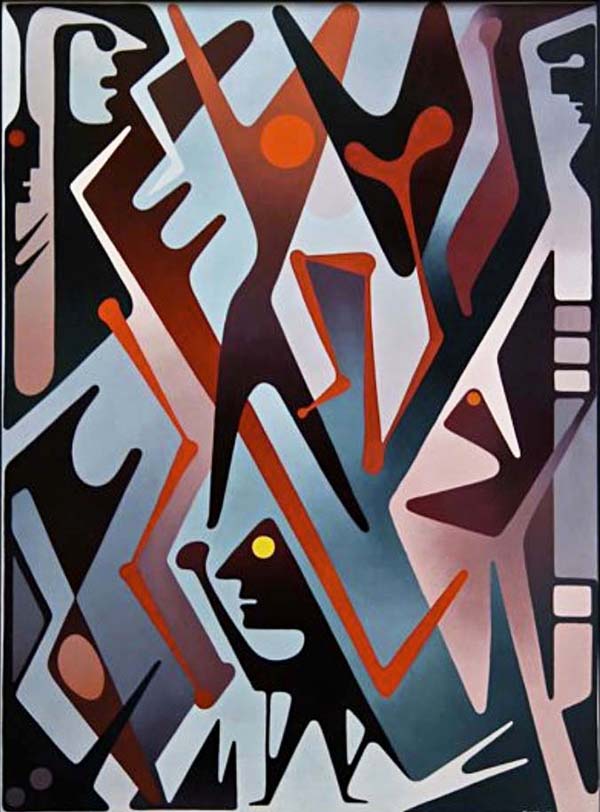

Although she put her art on hold for a while, Mary never dropped it entirely. Never an art world follower, she developed her own style and her own material, moving from ceramics to concrete in part because of the economics of running a kiln.

Fuller developed an unusual technique of quickly sculpting concrete. It involved adding vermiculite to the mix so it would solidify slowly. She'd use forms of wood or brick to rough out a shape, then when the consistency was right, she'd go to work.

"You have to be fast because [the concrete] is setting up," Mary says. "It's almost like making beach sculpture."

"I like to work fast. I'm not a person who goes over [things] a lot," she says. She still works, using an assistant to do the heavy lifting.