First and Foremost - Page 2

|

1 PARK PLANNED HOMES

Altadena, California

Architect: Ain, Johnson & Day

1946: first homes sold

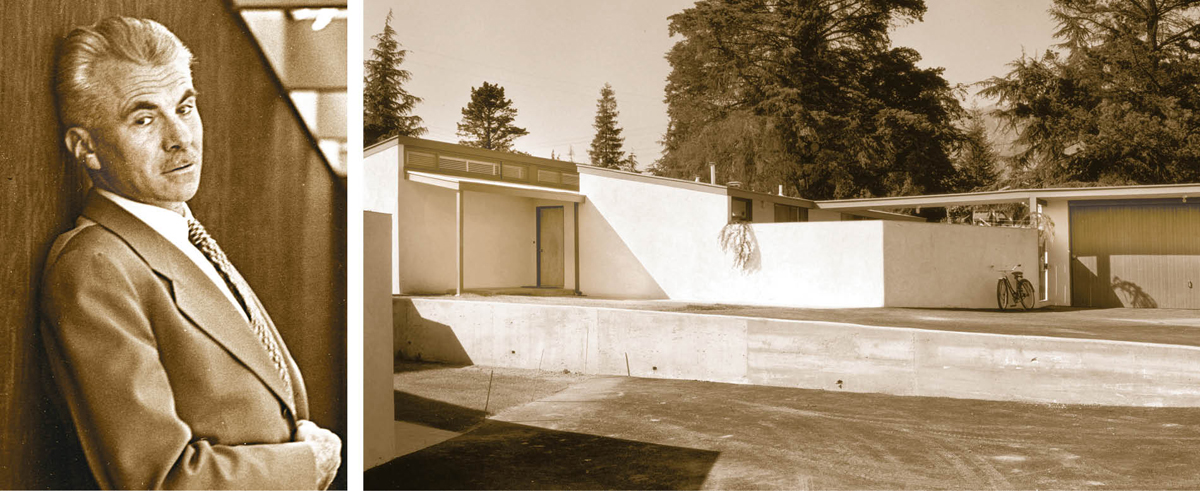

Architect Gregory Ain (pictured above), a Socialist, worked with like-minded developer Robert Kahan and landscape architect Garrett Eckbo on this tract in the Altadena hills, which remains well preserved to this day.

"Too many architects in their zeal to promulgate new and frequently valid ideas withdraw from the common architectural problems of the common people," Ain said.

And Kahan said of his partner: "Ain was determined to build nothing but cooperatives. By that time he was well known and could have done large commercial buildings, he could have been a great success. But his heart was in social housing."

Housing was in demand after the war, as GIs returned to find a housing market that had not grown, except for war housing for the previous five years. And much war housing was slated for demolition.

Ain, whose firm was Ain, Johnson & Day, based the Park Planned homes on his One Family Defense House project from the war, but the homes were far from barracks.

The three-bedroom, two-bath homes (like the one pictured above), with identical, 1,600-square-foot plans, had living areas opening onto private courtyards. The builder called the homes, on quarter-acre lots, "miniature estates." What may have been America's first modern tract was not entry level.

Homes were paired, with shared driveways, and without fences separating lots—to encourage neighborliness. The homes had interior gardens for privacy.

"Ain was presenting a postwar subdivision that embraced a more communal lifestyle, with ample opportunity for interaction among families," art historian Brooke Ashton Devenney wrote.

Close to a decade later, builder Joe Eichler would make national news when it got out that he would sell his homes to Black people and other racial minorities. According to Devenney, Ain and Kahan were prevented from doing so at Park Planned Homes due to restrictive covenants required by a federal housing agency.

And, shortly afterwards, when Ain and Kahan proposed to build racially integrated cooperative housing, for Community Homes, Inc., in nearby Reseda, the project died because lenders said no.

Ain helped design yet another pioneering tract in 1947, with houses built a year later: the Modernique Homes of Mar Vista in West Los Angeles. Twenty-eight were built, of a planned 100. Original plans called for Mar Vista to be cooperatively owned, but not enough people joined the co-op, so the homes were sold individually.

|

2 BEL VISTA

Palm Springs, California

Architect: Albert Frey

1946: first homes sold

Another pioneering tract was intended as a commercial venture, not as a social experiment. Builders Culver Nichols and Sallie Stevens Nicholls were prominent Palm Springs investors and developers.

But the 15-home tract was rooted in both farmworker and war worker housing. Architect Albert Frey (pictured above), who had designed farm housing for the Department of Agriculture in the 1930s, originally intended the designs for Bel Vista to house defense workers. The plan of the Bel Vista homes resembles Frey's farm housing.

The Swiss native had a history with social housing, having worked on housing projects in Belgium and with Le Corbusier in France. In 1928 Frey designed a "minimal metal house" in which, historian Joseph Rosa writes, "all of the private spaces and the kitchen spin off of the living area, eliminating the need for corridors."

Frey, who moved to New York in 1930, designed with partner A. Lawrence Kocher the 'Aluminaire' house that same year as an experiment in simple housing that could be built quickly. The Aluminaire—the name blends 'aluminum' and 'luminous'—is now owned by the Palm Springs Art Museum.

While small—1,100 square feet—the wood-framed Bel Vista homes had style, with big windows, seven doors each, and one curving concrete block wall. Each home has three bedrooms, a flat roof, and is built on a concrete slab, like so many modern tract homes that would follow.

Todd Hays, who owns the last of the homes that fully retains its architectural integrity, successfully had the home added to the National Register of Historic Places.

While the plan of each home was identical, the tract avoided monotony. Hays wrote in the National Register nomination: "The simple solution called for one single plan to be flipped, rotated, and placed with an altered setback from lot to lot."

"Eighteen different exterior finish colors were used to further differentiate the homes from one another," he wrote. Hays summarized how European modernism fed into American suburbia:

"Frey combined an International Style inspiration from his time spent in Europe and his early practice in the United States with the economic demands of postwar America to create a unique, early modern housing type both practical for the California desert and affordable to the everyday working person."