Home-Run Pursuits: Working at Home the Modern Way - Page 3

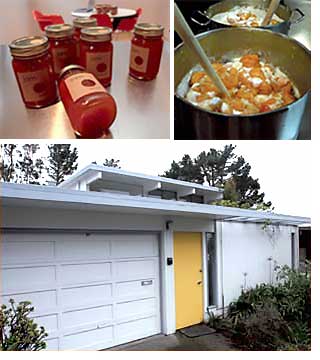

Inspired, Haeberli sent a few jars to the food magazines along with a press release praising the Blenheim apricots that once filled much of the Santa Clara Valley before being displaced by suburbia and silicon wafers. 'Food & Wine' magazine ran a short blurb. "They said it was the best jam they ever had," Haeberli says. "We were nowhere at all prepared for the deluge of requests for jam," he says.

Today the firm has a commercial kitchen, but much of the work still takes place in Haeberli's Eichler. "All the recipes are tested and developed in our home kitchen," he says. "We fine-tune them in the house. I find working in the house much more relaxing. It's the Eichler setting. Commercial kitchens don't have floor-to-ceiling walls of glass."

Haeberli, by the way, is a serious student of modern design. His current project—writing a book about Hendrick Van Keppel.

WeLoveJam, which uses recyclable and biodegradable packaging only, is also helping preserve Santa Clara's Blenheim orchards for future generations, Haeberli says. "There are only a few of these orchards left," he says. "Slow Food USA has them on the endangered list. For more: welovejam.com

Photography: David Toerge, WeLoveJam

Sydell Lewis

At-home abstract artist

Eichler home, Sunnyvale

Most abstract artists don't appreciate people looking at their paintings upside-down. But for Sydell Lewis, that's the point. "I'm hoping to open up the way people look at things," she says. "It's almost like addressing a prejudice."

Lewis, who works in a Sunnyvale Eichler, mounts her canvases on motors that rotate the paintings regularly—one minute, ten minutes, 15—at the viewer's discretion. The paintings are displayed vertically, horizontally, and at an angle. "It turns out a lot of people like these diagonal positions," she says.

"Rotating is not gimmicky," says Lewis, a retired chemist who's been painting full-time for 16 years. "It's not a shtick. It came out of my work. It contributes to how you see things. I think it adds a certain dimension. If you think about it, art should work upside down if it's composed well."

It seems to be working for Lewis, who shows her work at several galleries, including Gallery House in Palo Alto. Her work is also displayed in restaurants, at Kaiser hospitals, and in corporate collections.

Lewis, who loves working from home, says she made some modifications to make that possible. "I decided I didn't want toxic materials so I work in acrylic. There's no odor. It's compatible with my lifestyle." She even uses acrylic paint for her monotype prints, which is unusual. "Most prints are soft colored and muted," she says. "That's not what I do."

She does find one problem with working in a light-filled Eichler—too much light, especially on winter afternoons when it pours through the atrium into her studio. "I just work around it," she says. For more: sydellart.com

Photography: David Toerge

Jim McCormick

At-home piano instructor

Alexander home, Palm Springs

Jim McCormick, a Mid-Westerner who never appreciated Los Angeles' traffic and noise, relocated to the desert in 2002. "I wanted a quieter place as an artist, and there was something peaceful about the desert," he says. "The desert just drew me."

Since then, he has become an important part of the Coachella Valley's musical scene. He founded a popular awards festival for piano students with the Steinway Society, and has become an esteemed piano teacher who often educates fellow teachers.

McCormick, who favors Chopin, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, says he's happiest when teaching. "You need first of all to be very patient, patient with others," he says, "sensitive to what's going on with another person physically, perceptually, emotionally. And you need a thorough knowledge in life's experience of playing piano."

McCormick, who used to be on the faculty at the University of Southern California and Cal State Long Beach, still sees students several days a week in the Los Angeles area. But most of his teaching takes place in his Alexander home in Palm Springs.