How BART Got Art - Page 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Richmond, he created the strangest work at any BART station, a rather disquieting (for a transit system) relief incorporating fiberglass and seashells, in iridescent oranges, browns, and greens, that suggests undersea life and swirling galaxies.

At Lake Merritt, a circular courtyard that surrounds a forgotten fountain is filled with Mitchell's reliefs of mystical birds and sea life. Portholes in the mural used to let just plain folk peer into BART's operations center to see how trains were controlled.

At the 16th and 24th Street stations, sister stations with similar, attractive vaulting and varicolored matt tiles, Mitchell installed amazing concrete high reliefs along stairs and escalator entries. Images that emerge from the abstraction suggest Cubist faces, Jean Arp-like surreal swirls—and movement.

Mitchell's focus on movement is seen clearly at the Embarcadero station, where train riders whizz past a series of circles and partial circles inscribed on the walls. Few people realize that this is even art. But it captures the feeling of objects receding into the distance as you zoom by.

At a Market Street entry to the station, Mitchell inscribed these patterns into a frieze.

One of the most prized stations in the system, Glen Park, "a great and handsome place, bright and open, with daylight from both sides and from a large skylight above," according to a 1974 article in Architectural Record, has a set of marble murals that "gives elegance and richness to the room in a manner transit facilities have not enjoyed since the great days of the railroads."

The architect of the station, Ernest Born, designed the art himself. He traveled to Carrara, Italy to choose each piece, "about 30 different marbles in nearly a hundred different sizes and shapes," he wrote.

Although, over the years, some of the original BART art has disappeared—a super-sized directional arrow by John Wastlhuber at Coliseum station; an abstract design filling the lobby wall by Esherick at San Leandro, a fiber work by Barbara Shawcroft at Embarcadero, removed because it was too expensive to clean—most of the art remains intact.

And the art has its fans too.

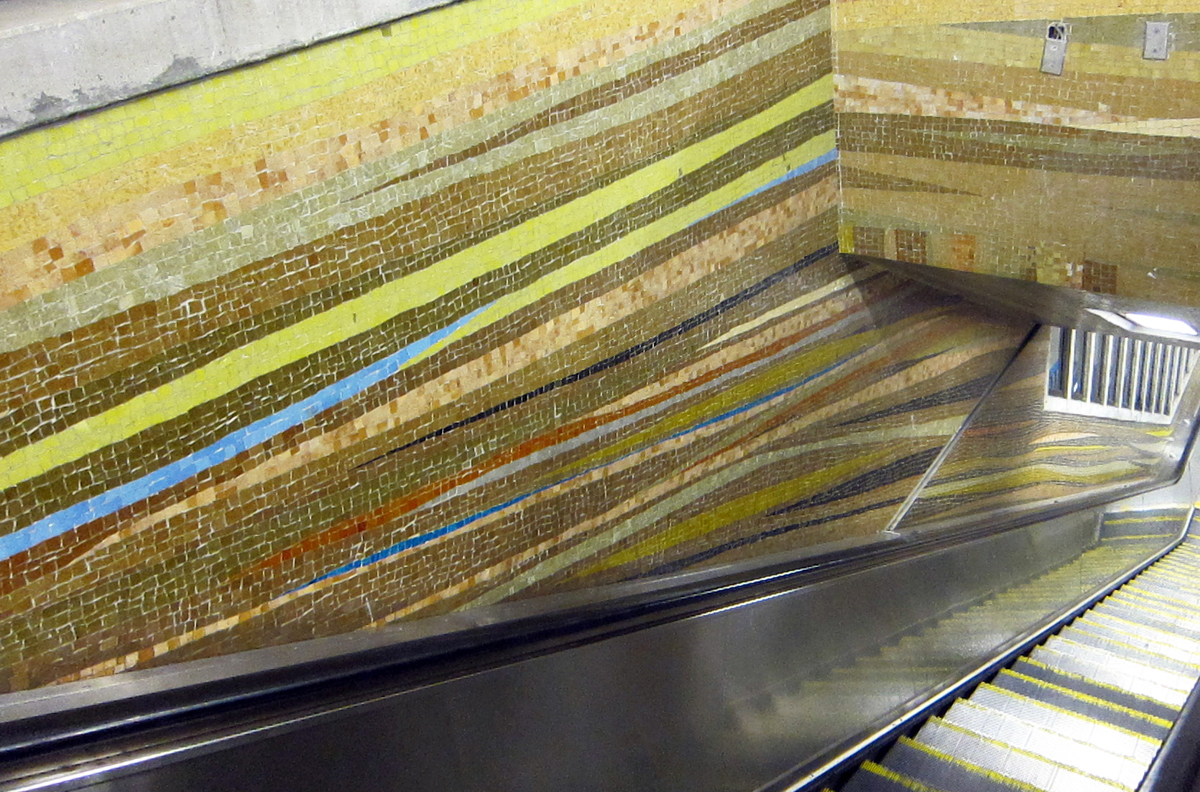

"When you come home to a station, it's like being home," Regina Almaguer says, recalling the days when she passed daily through El Cerrito, admiring the abstract mosaic murals by Pardiñas. "I'd go down the escalator and see the murals. They're so beautiful. 'I'm home now.'"

Photography: James Fanucchi, Thomas Hawk, Dave Weinstein; and courtesy Ilka Erren Pardiñas, Joy and William Mitchell, William Cullen, Tallie Maule Collection (Environmental Design Archives - University of California), Berkeley), Ernest and Esther Born Collection (University of California, Berkeley)