It Starts with a Spark - Page 4

|

|

|

The interview summarizes: “His wife complains that he is too often on jobs and is ‘not even interested in Christmas.’”

Do creatives seek excitement? Do they take risks? Anshen suggests so. In his late teen years, after his wealthy dad lost much of his fortune, Bob did have to find work—in the trust department at a Wall Street bank.

He was good at his job, but it was not for him. “I didn’t like the idea of the stodgy, sedentary, wait-25-years-and-you-maybe-earn-$10,000,” he said. So, in 1931 he quit to study architecture.

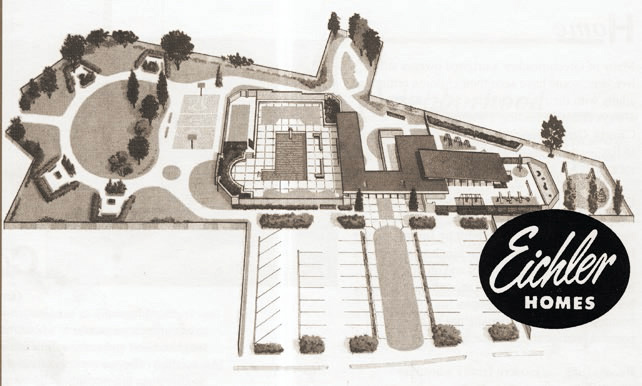

Anshen cited the Eichler subdivision Fairmeadow as a creative achievement, because it was designed as an experiment arraying homes on “interlocking circular streets.”

“The planning commission dubbed it ‘Hot Rod Circles,’ and the police department went wild, and the post office department nearly went out of its mind numbering the things,” he said.

The circular street plan provided variety, he said, “so that’s an amusing thing.”

|

Does a bit of rebellion add to creativity?

It seems that way from Anshen and Allen. Anshen describes their training in a school “so conservative it made good radicals out of us.” Anshen claimed to be one of the rebel leaders. “It was a marvelous time to know the professors were wrong,” he said.

Both Anshen and Jones emphasized the ‘importance of persuasion’ to success as a creative architect. Anshen went back to his oft-repeated tale about how he and Steve Allen sent a check for $100 to buy time to present their plan for a mansion to a Standard Oil executive.

Not only did they convince the exec to build a modern home instead of an English Gothic, they won a client they would retain for years. It was their first job.

Jones cited his ability to communicate with clients as one of his strengths.

But really what it takes to be a creative architect, Anshen said, was vision. He called it “the ability to conceive of the appropriate design. And then—the qualifications necessary to make other people see that that’s just exactly the way it should be accomplished.”

|

|

|

There’s a sadness in the study as it addresses Anshen. His interviewer read the man all too well. In earlier days Anshen was known as a skilled and energetic raconteur.

But by 1959 this skill was slipping. “Sometimes I had the impression he attempts to carry off the elder-statesman, storytelling, bon vivant role,” the psychologist writes, “but lacks the commanding presence required for the role.”

“On the surface he is very calm and smooth and reasonably likeable,” the interviewer wrote. “But such symptoms as strong denial mechanism, nervous shaking, heavy drinking, and frequent sexual allusions give the overall impression that Anshen is paying a heavy price for his external smoothness.”

Five years later Anshen died accidentally at age 54 of what the coroner called “barbiturate and alcohol poisoning.”

|

|

|

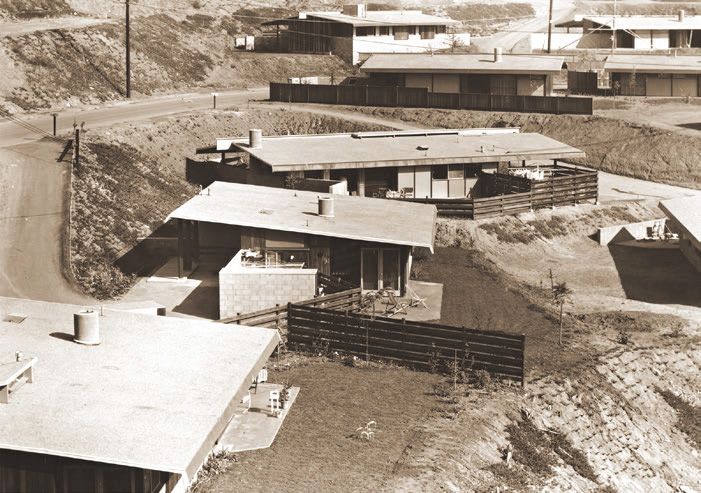

Working for Eichler, Anshen and Jones created a version of modernism that was warm and inviting in its textures, colors, use of wood and brick, and of glass to open to the out of doors. Can we see the influence of their travels, their childhood friendships, their social conscience, their sense of history?

It’s hard to say no.

Anshen in particular appreciated history and the way it influences people in the present. After talking about ancient Greek and Roman buildings, structures from the Middle Ages, “the Chinese and Indian and Japanese,” and “the Egyptian thing,” he mused: “I think that you have to have an awareness of the development of the history of ideas and the thought of mankind in order to even begin to be a good architect.”

Special thanks: to the Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California, Berkeley, for generously providing access to materials from the Architect Assessment Project. And to Pierluigi Serraino for facilitating our use of the Creative Architect Study, for other assistance, and for bringing this lost study to light through his book ‘The Creative Architect.’

Photography: Ernie Braun, Dale Healy, Brian Scantlebury, Julius Shulman (© J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles - 2004.R.10); and courtesy Institute of Personality and Social Research, A. Quincy Jones Papers (Special Collections - Young Research Library, UCLA), Crestwood Hills Archive, John Anshen, Rico Tee Archive

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4