It Takes Two

|

|

|

"Whatever I can do, Ray can do better," mid-century modern design legend Charles Eames used to tell people. But how many believed him?

Throughout their careers in Southern California as a husband-wife design team—creating furniture, architecture, exhibits, and more—Charles and Ray Eames exemplified the idea of conjugal partnership in the arts.

But their career together, and their lives together, also suggest some of the challenges. The Eameses divorced after Charles took up with another woman. And no, not everyone believed him when he credited Ray (who was born Bernice Kaiser) as his equal partner.

When the two appeared on TV or were interviewed by the press, Ray was often referred to as his assistant—if noticed at all. Ray, for sure, was shy, and Charles was a showman. Clearly, few back then could conceive of a woman as an artistic innovator.

"But since her death in 1988," as the New York Times wrote in a profile of Ray last year, "Ray Eames has been moving back to the center of the picture. Or rather, the world has been discovering that she was there all along—not just as the beaming helpmeet with sparkling eyes and a Dorothy-from-Oz dress sense, but as an artistic force in and of herself."

|

Throughout the mid-20th century, California produced a strong crop of partners in life who were also partners in the arts—or at least frequent collaborators. It was hard honing our final list down to eight couples.

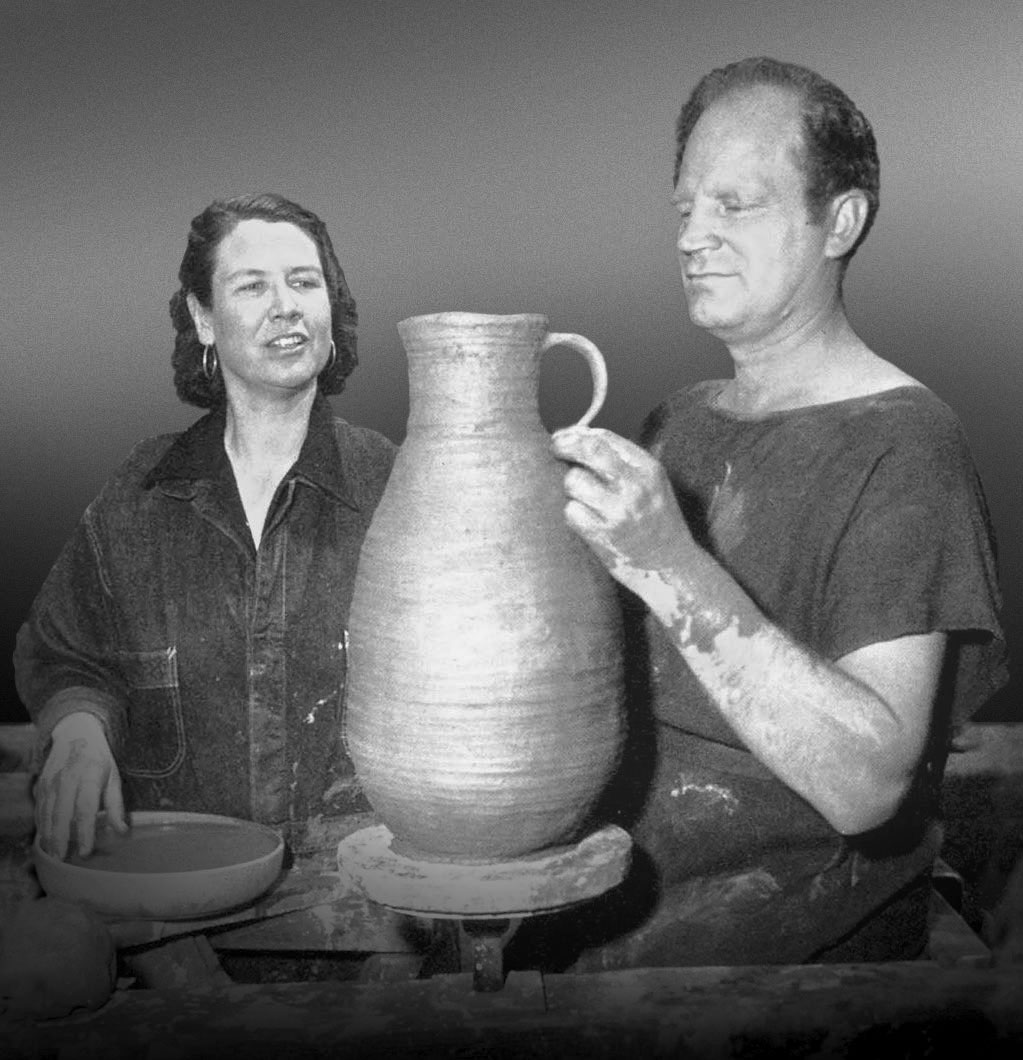

Why not potters Otto and Vivika Heino? Or Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz?

Each one of the eight vignettes that follow tells a different aspect of the story of two Californians weaving together their lives and artistic endeavors. They reveal some of the challenges and how they can be overcome.

These profiles show that working together can be tough. Three of the couples profiled here divorced.

The stories also show that, in some cases, great artists might not have triumphed in the way they did without the help of the other partner. Southern California potter Gertrud Natzler's delicate ceramic forms, for example—what would they have been without her husband Otto's intense glazes?

"Even the most violent glazes are held in a state of restraint by Gertrud's thin, gently curving shapes," reporter Lisa Hammel wrote. "Deep, crusty pocking, for example, forms the surface of a slender slice of bowl."

|

And would Otto have been a potter at all without Gertrud? After she died young he stayed in clay—making sculpture, not pots.

Would Bay Area-based Lois Langhorst have gotten as far as she did in architecture had she not been married to architect Fred Langhorst and formed Langhorst & Langhorst? Likely not, thanks to undisguised discrimination against women in the discipline, though Lois' talents were great.

Inge Horton, architect and author of Early Women Architects of the San Francisco Bay Area, found precious few women architects who made a mark as designers during the mid-century, though any number worked in architect's offices in subsidiary roles.

It's interesting too how two people in a loving relationship often found themselves with distinctly different skills that proved complementary. A musician—and a builder of musical instruments. An idea man with bright ideas about Black music and Black life and publishing—and a wife who could make things happen.

What's love got to do with it?