It Takes Two - Page 3

3. GERTRUD AND OTTO NATZLER

|

It was love that turned Otto towards pottery. A frustrated violinist denied admission to the academy in Vienna, he turned to textiles and was designing neckties until the Nazis shut the factory in 1933 because it was owned by a Jew.

Otto's marriage was coming to an end when he met Gertrud Amon. One bio writes: "He expressed an interest in ceramics primarily as a way to get to know her better."

Otto wrote: "We discovered simultaneously clay and each other. If it had not been for that rainy Sunday in July of 1933, we may never have met and neither of us probably would have progressed very far with clay."

"Somehow the medium itself seemed much more fascinating to us" than what ceramicists were producing with it, Otto wrote. "We both felt we did not want to 'learn' and went into 'seclusion' by renting our first studio in Vienna."

They experimented ceaselessly, Otto methodically recording every glaze ingredient, every clay recipe. "Efforts directed toward achieving an ordinary glaze resulted in crusty surfaces, full of pockmarks, holes, and blisters," he wrote.

|

|

|

The Natzlers, Jews, fled Austria as the Nazis approached, arriving in Los Angeles via the Panama Canal in 1938, eventually living in the Hollywood Hills.

Gertrud (1908-1971) threw the pots, Otto (1908-2007) glazed them in a variety of styles, smooth and sleek, but more often pitted, volcanic. Together they produced work neither could have done on their own.

One of the few ceramicists in the state who could use a potter's wheel, Gertrud taught the skill to others. Her vases, bowls, and plates were deliberately simple, classical in feel.

The Natzlers produced prodigiously. At the time of their early retrospective at the Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art in 1966, they had a catalog of 23,000 pieces.

They were rewarded with loyal collectors, many museum and gallery shows, and were widely regarded as masters.

Just as they had retreated from the world to develop their art, they continued to remain apart from others artistically. "Their work was not influenced by fashion, artistic movements, or the philosophies of others, but stood alone and independent," Dominic Bradley wrote in his tome, Mid-Century Modern Complete.

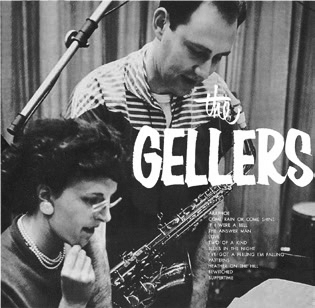

4. HERB AND LORRAINE GELLER

|

Husband-and-wife jazz instrumental teams were rare back in the day—because few jazz instrumentalists were women.

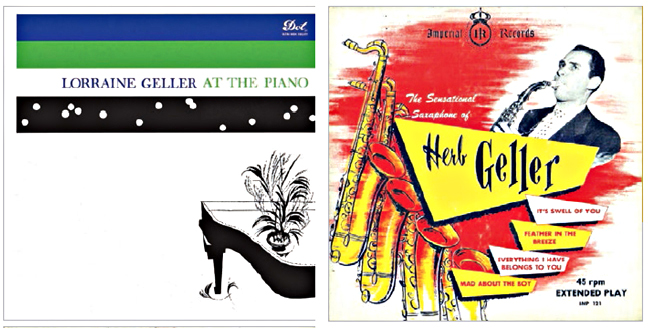

Lorraine (Walsh) Geller (1928-1958) recorded in a quartet and sextet with her husband, Herb (1928-2013), as a soloist, and played with such stalwarts as Charlie Parker and Zoot Sims, in the mid-1950s, when she and Herb were centerpieces of the Los Angeles jazz scene.

Working together, the couple produced a unique sound that neither could have done without the partnership. Herb played alto sax, mainly, and Lorraine piano. "Herb and Lorraine created a distinctive harmonic quality between their two instruments," fan Richard H. Bauer wrote.

Lorraine, who'd met Herb circa 1950 while playing New York with the 'all girl' and racially integrated big band the Sweethearts of Rhythm, played with "a vibrant rhythmic sound and extensive harmonic knowledge," critic Ron Wynns wrote.

Their combo music ranges from jittery, high-speed bebop to soulful, crying ballads.

|

|

|

As an alto player in L.A., Herb was up against such sax stars as Bud Shank and Art Pepper but, historian Noal Cohen has written, "Geller's playing was more vital and moved me in a way the others didn't."

The Gellers were a hardworking team. "Lorraine and I became involved with learning as many songs as possible by different composers—Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Jimmy Van Heusen, Jule Styne, and so on," Herb told jazz writer Marc Myers. "We did this to build a big repertoire. I don't think anyone knew as many songs as Lorraine and I did back then."

In California the Gellers built their careers in part by playing at strip clubs. "Strip music was the best thing for training your stamina and building chops," Herb said.

For years he and Lorraine led a combo Tuesday nights at Zardi's on Hollywood Boulevard, attracting a diverse audience. For a time Lorraine was house pianist at the famed Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach.

Lorraine died of pulmonary edema in 1958 while Herb was on the road with Benny Goodman. She had asthma, and just had a long recovery after giving birth.

"I was devastated and had no idea what to do. Lorraine had been my entire life," Herb told Myers. But he had a daughter and had to work. "I re-joined Benny and finished the tour."