Jim San Jule: Tireless Crusader - Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

San Jule’s main technique, however, was more straightforward—schmoozing. He was able to bring people together because he knew everyone—mayor after mayor (Shelley, Alioto, Feinstein); architects, landscape architects, and planners; men of high finance; everyone at Washington Street Bar & Grill; writers, intellectuals, and newspaper reporters.

“He was very good at getting people together and getting things done,” his son Steve San Jule recalls. “He was direct, right to the point. He’d stare at you, and you knew you had to come well prepared or he’d eat you alive.”

Often enough, San Jule succeeded. San Francisco is dotted with housing and mixed-use developments he inspired or pushed to completion, including the Golden Gateway redevelopment of the early 1960s, Tishman’s 1,300-unit Fillmore Center on Fillmore Street near Geary Boulevard, Franklin Square near St. Mary’s Cathedral, and the Central Waterfront, which is only today seeing the sort of development San Jule began pushing 30 years ago.

Through it all, his motivation was never money.

Chappell groups San Jule with ‘the housers,’ socially progressive planners, architects, and activists who grew up during the New Deal. “He was motivated by social concerns.”

In 1999, when SPUR gave San Jule its Silver Spur award, the group cited his responsibility for more than 3,000 units of housing in the city—a significant understatement, even leaving out the Central Waterfront.

According to Koshland, who met San Jule in 1950, shortly after he joined Eichler, and married him in 1954, it was San Jule’s experience with Eichler that made housing his career. But San Jule had already learned by personal experience that decent housing was important and that integrated housing worked.

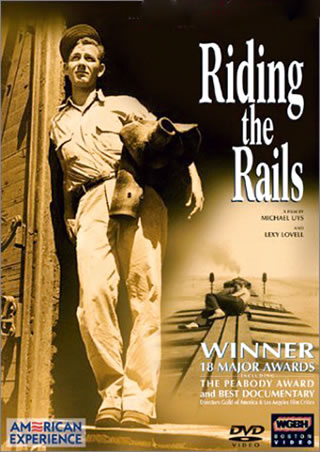

He spent his impressionable years of 17 and 18 homeless, and during the early years of World War II lived in one of the very few integrated housing projects anywhere in the country—Marin City in Sausalito.

“A completely successful example of a non-segregated housing project,” the magazine Task said. Task was a planning and architecture magazine whose contributors included many progressive designers including, for one article, San Jule’s soon-to-be friend, architect Bob Anshen.

San Jule also may have had two other significant exposures to social housing issues pre-Eichler.

San Jule told his two sons from his first marriage, Pete and Steve, that he’d worked with John Steinbeck, in the days before The Grapes of Wrath, on reports about the ‘Hooverville’ migrant camps that sprang up in California to accommodate Dust Bowl immigrants, who slept beneath what Steinbeck described as filthy rugs in shanties of “willow branches” and “wattling weeds.”

Steinbeck’s reportage, published in newspapers and pamphlets, was fodder for a San Francisco nonprofit, the Lubin Society, that sought tougher laws against labor exploitation and for federal housing, in Steinbeck’s words, “to restore the dignity and decency that had been kicked out of the migrants by their intolerable mode of life.”

Publications of the Steinbeck material do not credit San Jule. But whether he worked with Steinbeck or not—and, given his interests and the progressive circles in which he moved, San Jule may have been involved with the Lubin Society—the fact that he bragged about his involvement shows he was focused on the issue of farm-worker housing.