Learning from the Land - Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And in Sausalito, illustrator Beth Cope often sees quail grazing on the grass-covered roof alongside her drafting table. Her husband Newton, who mows the roof, enjoys watching coyotes and deer prance across it. "A bobcat looked into my window, actually came up to my window and stuck his face in," Newton says.

Bowman's homes are almost always in the country, or at urban edges that might as well be country.

Bowman, 75, has told colleagues "I have three priorities in life, in order," Silva says. "His fishing, architecture, and family."

But fishing doesn't mean Bowman's a slacker. Whatever field Obie tackles, friends say, he does so full tilt. Until age slowed him, Obie was a champion bass fisherman.

"He'd rather be in nature" than at some architectural confab, Arkin says. "That's where he finds the inspiration that feeds his good architecture. He talks about the real source of inspiration, nature, and fitting the environment."

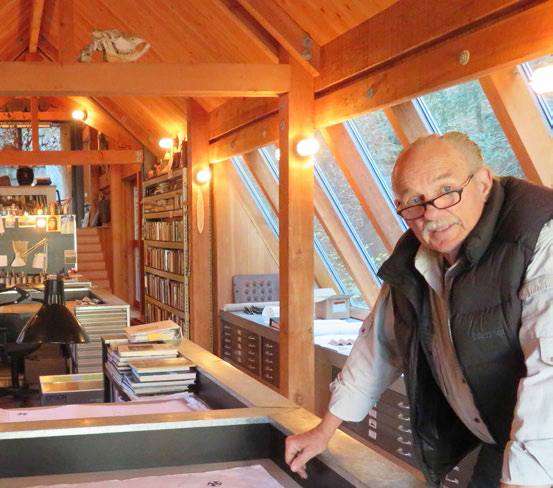

And Bowman's family? Wife Helena has been the small firm's business manager from the start, his rural Healdsburg studio shares a property with his home, and his four children grew up with the succession of young architects who worked for him. Daughter Ántonia became an architect like her dad.

"Working on his property and near his house, you get to know him well," says Andrew Scheidt, another architect who early on worked for Bowman. Bowman's firm has never exceeded seven architects. Recently that number was one.

By the early 1970s, ecology was just beginning to take hold as a value among architects. Little attention was paid to the topic when Bowman studied architecture (University of Southern California, UC Berkeley, University of Arizona), he says. At Arizona, fellow student Steve Martino recalls, Bowman stood out.

"The developers back then and still today were building artificial lakes and putting houses around them," says Martino, today a landscape architect. "Obie seemed to be more environmentally sensitive and conscious than most people. He said, 'Those lakes, they're stupid.' That's pretty blunt. We have nine feet of evaporation here every year, so it takes a lot of water to keep these things going.

"I guess you would say he was intense."

Indeed, Bowman is known for worrying about every little detail, from how each and every line is drawn on a plan—to ensure the contractors get it right—to interviewing the foremen on his jobs to make sure they understand his way of doing things.

Kat Guinn and Mike Howland had Bowman transform their bland Sebastopol ranch house, creating an open-beamed central kitchen clad in corrugated metal.

Bowman's signature 'heat chimneys,' inspired by their use on the historic hop kilns that dot the Sonoma area, lower the temperature inside the Guinn-Howland kitchen significantly by sucking warm air up and away.