Light as a Stone in Flight - Page 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"It's a very unique art form because just finding the rock itself is part of the art form," she says. "You have to understand the rock, how to work it. It presents a very unique set of challenges for the artist. The materials are coming from the earth, so you have an aesthetic that is sort of peaceful and earthy and Zen-like. Those are qualities that are imbued in Ken's work."

A Matsumoto stone vessel seems like a natural thing for a garden. But Ken prefers them inside. "Because outside you sort of expect to find stone. Inside, where everything is controlled and man-made, bringing a piece of unfinished stone in…well, I think my pieces benefit from the contrast."

Matsumoto, who studied industrial drafting in high school, turned a former walnut shelling plant into an art-making factory in his outdoor studio in the heart of Japantown. He uses a diamond-bladed angle grinder to cut into raw stone that is rotating on a turntable, which is also of his own devising.

"I'm able to swing [the blade] into the stone that it sits above, and make these perfect cuts, so I end up with a very symmetrical bowl," he explains, referring to his best-known series of works, his stone vessels.

It's a messy process, with water jetting at the stone to prevent overheating, and stone dust flying. Matsumoto wears a mask and something like a hazmat suit. "I was recently diagnosed with asthma," he says. "I think this must have been a contributing factor. Recently I've been taking more precautions."

After cutting, Matsumoto turns to polishing—but polished stone is not all that his art is about. Much of his stonework remains natural and rough.

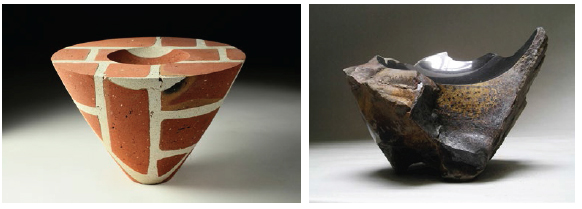

One of Ken's signature elements, says Cathy Kimball, executive director of the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, is "the way the finely polished stone is juxtaposed with the raw rock it came from—the tension between the two."

"I see Ken as a sculptor," Kimball says. "Stone is one of his mediums, but he works in others, including glass and bronze. He's not just making vessels. They are truly sculptural works of art that might also have a utilitarian function."

One of Matsumoto's popular pieces involved no stone at all—though one can see a memory of stone in the work. It's a series of transparent glass sheets, one in front of another. Look through and you see a void, shaped like one of his stone vessels. The effect is a bit op art, and absolutely weightless. Each sheet was hollowed out by jets of water.

The dialog between man and mineral that characterizes Matsumoto's practice doesn't always work out, however. Part of his yard is a purgatory for stone sculptures that failed—or at least need work. "People still respond to it," he says of one, "but it doesn't really work for me."

By turning stone into vessel-like forms, Matsumoto's work deals with human history—and the human present. The form also gives his work an approachable quality.

"It turns out all cultures have that functional thing—a vessel, a bowl, a cup—everybody has something like that," he says.

Although Matsumoto is a Sansei, third generation Japanese-American, and his studio and gallery are in the heart of San Jose's Japantown, he doesn't see his art as Japanese in style. But others do, including Kumiko Iwasawa, a scholar of Asian art who grew up in Japan and runs a gallery in Los Gatos.

"His attitude, his way of thinking, it's very Japanese to me," she says. "We don't have these sort of people in Japan anymore." Iwasawa owns Iwasawa Oriental Art, a gallery where visitors can see Matsumoto's stone works in front of her building, and more of it inside.