Loving the Highlife in Crestwood Hills - Los Angeles - Page 3

Houses are arrayed on the hillsides, which were terraced to create building pads, to take advantage of the views. Although most of the homes are quite close to each other, the contours of the terrain, and the dense shrubbery and trees that have grown up since construction generally hide neighboring homes.

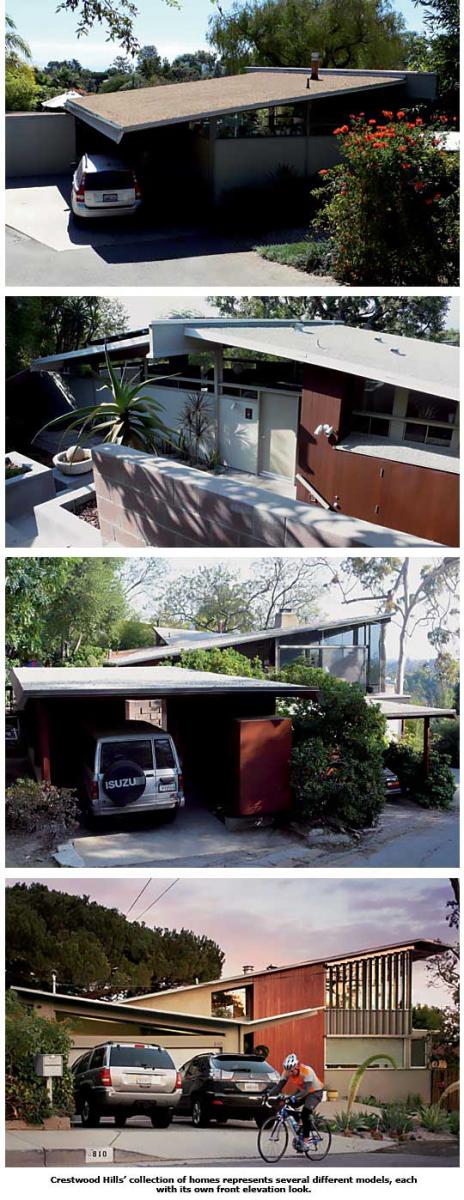

Since the sites varied, so did the houses. Split-levels are common. Owners got to chose from several uphill and downhill plans. There are single-slope shed roofs and butterfly roofs, sometimes rising to two-story height living rooms. Many have prow-shaped, glass-filled fronts, suggesting ships. Roofs and decks tend to be dramatically angular and boldly cantilevered.

Though Jones is most often credited as the architect, it was really a team effort that involved architect Whitney R. Smith, architect-engineer Edgardo Contini, and several draftsmen who also played a creative role in the designs, Buckner says, including Wayne Williams and Jim Charlton.

Zellman says Charlton, who trained with Frank Lloyd Wright, played an especially important role in the design, designing 18 of the 26 models that were eventually built, and siting the individual homes. Charlton, who worked for Wright when he was designing his utopian and never-built 'Broadacre City' of low-cost homes, gave the homes and site plan a strong Wrightian touch.

Wright's plan for Broadacre City "achieved its most complete realization" in Crestwood Hills, Zellman and Friedland wrote.

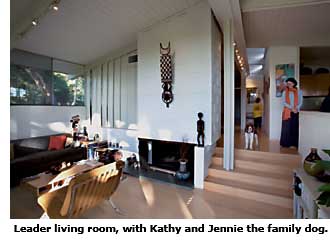

Diane Phillips, an original owner, lives in one of the most dramatic houses, wonderfully fitted to a tricky hillside site. It remains one of the most original. Steps from a carport rise one floor to the main living area, which is supported by steel beams. A brick fireplace opens both to the living area and to a den several steps higher. The living area opens to a small deck. Much of the interior is dark, Douglas fir plywood, giving it the feel of a mountain lodge.

Crestwood Hills morphed from a middle-class community to a neighborhood for the wealthy around the time of the 1961 fire, says Peter Israel, who remembers as larger homes began sprouting on empty lots. "Non-association people came in after first couple of years. There was such a big difference between the original homes and the ones that came in later," he says.

Many of the newer homes were designed by well-known modern architects—including William Krisel, Richard Neutra, Paul Williams, Craig Ellwood, and Ray Kappe—and add to Crestwood Hills architectural cachet.

Still, Crestwood Hills retains much of its original spirit, despite the run-up in prices, Wargin says. "You get a different kind of people than you would in the other areas up in the hills," he says. Homes in Crestwood Hills can sell for $2 million. Just down the hill, they go for $10 million or more. Nearby, they go for double that. "When you consider that, the homes here are pretty reasonable," he says.

Making a killing in real estate was far from the thoughts of the three Hollywood studio musicians who first proposed pooling their resources to buy a little land in the hills. But to make a cooperative work, more members were needed. "The idea just blossomed," remembers Nora Weckler, who heard about the scheme from friends.

Although the association bought the land together, individual lots and homes were individually owned. The goal was to run several services as cooperatives. Besides the nursery school, they hoped to have cooperative stores and doctors, and even a bus, Weckler remembers. But they would have needed more than 160 family members to make those services efficient, she says.

Why did the cooperative fail to achieve its potential? Economics played a large part. The homes proved more costly to build than anticipated, even though the architects hoped that by prefabricating certain parts, they could save money.

It also took much longer than anticipated to win governmental approvals and find financing. "By the time it got close to fruition," Israel says, "some people had gotten cold feet and wanted to withdraw. But there was no money to give them," he says.

Zellman says politics hurt the project as well. Federal officials opposed cooperative housing because it competed with for-profit housing, he says, and the Federal Housing Administration shied away from modern homes, considering them structurally unsound. Lenders also shied away because the neighborhood was going to be integrated—a first in the hillside district. The neighborhood's "reputation of being a cooperative got translated into being a bunch of Commies," Nora Weckler adds.