Mid-Century Jazz: Listen to the Cool

Although the late Ned Eichler's series of Bay Area talks in the 2000's was entitled 'I Now Sing For My Father,' it really had more to do with lauding the old man than with making music.

Although the late Ned Eichler's series of Bay Area talks in the 2000's was entitled 'I Now Sing For My Father,' it really had more to do with lauding the old man than with making music.

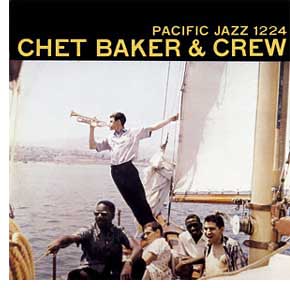

But if Ned Eichler had sung, it might have sounded something like the cool, airy vocals that the late Chet Baker breathed into the 1950s, when he put his equally cool trumpet aside. That's the sound Eichler favored in jazz, and it's a feeling seemingly in harmony with the ambience of homes originally built by his father, Joe ,and other builders of mid-century modern.

In his talks, Ned, himself a veteran of Eichler Homes' staff, insisted that "the Eichler homes could not have existed—and never did exist anywhere else—except for the confluence of the person (my father), the place (Northern California), and the times."

The same point could be made about what's come to be called West Coast Jazz (or Cool Jazz), a musical genre in which Baker, a sometime Californian, and other musicians rose in prominence during the same time period as California's mid-century modern homes.

Although the Cool Jazz players of the 1950s laced their set lists and albums with new versions of old songs from the previous decade and earlier, they arranged and performed this and their original material in a manner in harmony with the philosophy and design approach of mid-century modern architects: spare and clean melody lines that respected the open space between the notes and the instruments, and clear but compelling rhythmic patterns that elevated listeners without crowding them.

Some see Cool Jazz as significantly distinct from Bop, an often high-energy, high-speed form of jazz that was bred and based in New York in the '40s and '50s. On the other coast, in his home in Tiburon, north of the Golden Gate Bridge, Ned Eichler makes a point about two of Bop's foremost founders. "Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker—those guys weren't here," he says. "West Coast Jazz—yes, it was avant-garde in a way, but it wasn't sharp. It was nice!"

Cathye Smithwick and husband Charlie Anderson, who live in an Eichler home in San Jose's Fairglen and make music an integral part of their lives, echo the links between jazz style, geography, and the postwar era. "I think people were looking for a more laidback lifestyle out here at that time," says Smithwick. "I think Charlie Parker and the Bop guys were urban, [in a setting of] Broadway and a lot of crowding and chaos. And the Eichler homes, and the Cool Jazz that went along with them, were suburban-centric... Here, you don't feel crowded, constrained, or chaotic when you're listening to Cool Jazz."

Jazz critic Stanley Crouch, New York-based but California-born, has sought out the source of this cool approach to jazz. "The West Coast style mostly came from people responding to [saxophonist] Lester Young's way of playing," Crouch told PBS host Hendrick Smith.

"Now, he had a light tone," Crouch said of Young, a black player who got his start in Kansas City before moving to New York with the Count Basie band in 1936. "He, as they used to say, swung like crazy, with a very poetic approach to playing.

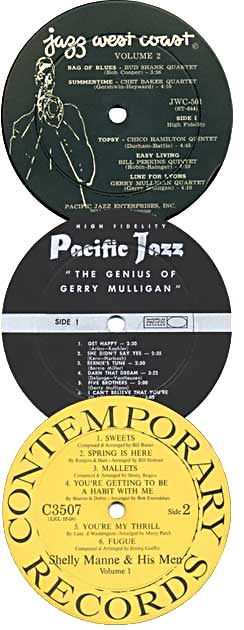

"So, a lot of white guys zeroed in on him. They liked his approach to playing." Among the influenced were Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Paul Desmond, Dave Brubeck, and Shorty Rogers, all rising western stars of the 1950s.

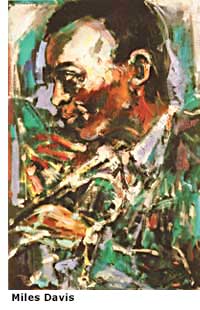

But alongside Young, consider the significant influence of black trumpeter Miles Davis and the 78rpm discs he recorded in 1949 and 1950, finally collected on a long-playing album in 1957 under the title 'The Birth of the Cool.' By the time of that LP's release, the restless Davis had already gone in different directions. But the plaintive, seeking sound of his horn on those early sides, as well as his LP projects with arranger Gil Evans, had helped define 'cool' for a national and global audience.

The return of the recording industry after a wartime ban on the use of shellac, a vital ingredient at the time for record manufacturing, allowed jazz artists to be heard on jukeboxes and a growing number of radio stations, as well as in clubs all over the country. All of this resulted in a healthy amount of cross-pollination of styles.