Modern Architecture: Pyramid Power - Page 2

The pyramid houses are built on a square or nearly square first story base (36 x 36 feet or, in Wiens' case, 36 x 38), with the second and third stories within the pyramid itself. The houses have a master bedroom and a living-dining-kitchen area on the first floor; and two bedrooms, linen closet, and laundry on the second floor. Wiens' house has a second story that rises cathedral-like to the apex of the pyramid.

The other model layers another story into the pyramid, an attic room atop a flat-roofed second story. Upstairs windows pivot open, numerous skylights and clerestory windows provide superb illumination, closets are hidden beneath the slope of the pyramid, and a second floor studio peers down into the living room through an interior skylight.

Less than a year after Wiens moved into his pyramid, a pair of artists knocked on his door. David Komar and Maria Winkler were interested in the pyramid down the street, which was being sold by its first owner after less than a year. Komar in particular was in thrall. "He fell in love with the pyramid and the third room on top," Winkler says. "We were a little cautious," Komar says. "Were there any problems, anything that could put us off?"

The answer, of course, was yes. But Komar and Winkler refused to be put off. Besides trapping cosmic energy, pyramid houses also trap heat. Komar, who loves his secretive attic room but found that he rarely used it, turned it into an exhaust room by installing a whole-house ceiling fan.

Wiens installed his fans on the first floor, just above the door to the backyard and below the skylight to his bedroom above. He also poked a skylight through the apex of his pyramid—no mean engineering feat. "It's fun to figure it out, and figure out what makes it work," Wiens says. "I'm an engineer and I fixed it."

Clearly it takes a special person to love a pyramid house—but not necessarily a believer in pyramid power. "We chose it artistically," Winkler says. "As artists, we're open to a lot of ideas."

"I do tai chi," she says. "That's as New Age as I get." "People say they feel good when they come in," Winkler says. "It's a very restful feeling."

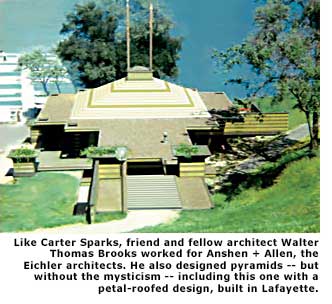

Pyramid houses have never been a mainstay of the modern movement. However, for reasons both practical and spiritual, they have intrigued architects. Walter Thomas Brooks, who was friends with Sparks while they were architecture students at the University of California, Berkeley, also went into pyramids—but without the mysticism. Brooks designed several community and park buildings, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Davis, a house in Berkeley, and other projects with 'pyramid' roofs opening onto a skylight. The goal was to span broad areas without using a truss, says Brooks.

Brooks, who spent most of his career as a sole practitioner, worked in the mid-1950s for Eichler Homes architects Anshen + Allen. One of his assignments was designing the unusual circular site plan for Eichler's Fairmeadow subdivision in Palo Alto. Sparks also worked for Anshen + Allen in the early '50s, but at a different time.

Brooks lost track of Sparks over the years, and knows nothing about his involvement with pyramid power. "That was a time of the pyramids, and the hippie movement," Brooks says with a laugh. "That was really in, in those days. I had no connection with that whatsoever."

One California architect who does take pyramid power seriously, however, is Mario Ciampi, who won international fame in the 1950s for a series of geometrically bold modern schools in Daly City and Pacifica, for urban design plans in San Francisco, and the Berkeley Art Museum. Ciampi is still working at age 99. He attributes that to innate strength and, among other forces, pyramid power.

For his own home in Kent Woodlands, Ciampi remodeled a hillside ranch by adding seven pyramidal roofs, some over the garden, and others over his studio, his wife's music studio, and his meditation room. He sees pyramids as energy centers that promote health and clear thinking. "These areas have to do with my cosmic consciousness," he says.

Carter Sparks' pyramids, however, never had much impact on the Central Valley's consciousness. "It was certainly a financial failure," Bill Streng recalls. "Our labor costs were high on it," Jim Streng says. "There was a lot of cubic space but not as much usable floor space. There was higher per-foot cost."

"We didn't build enough of them to get efficient at building them," he adds. "After you build ten of them, you find ways of doing things more efficiently."

Also, Bill concedes, "We really didn't promote them."

"We never built a model and furnished it," Bill says. "We built a couple, talked to people about them. People weren't interested. Maybe if we had furnished a model, they would have done better. We won't ever know."

Photos by David Toerge; others courtesy Jennifer Sparks, Walter Thomas Brooks

Discover more about Sacramento's Strengs from Eichler Network's Preferred Service Company Realtor Steven Streng.