The Mystery of the Eichler Atrium - Page 2

"At one point he drew what is an atrium. My father looked at it and said, 'What the hell is that?' And Bob said, 'It's an old, old thing, people used it long ago.' And he called it an 'atrium.'" But it wasn't a Eureka moment. "People at the meeting saw there would be construction problems," Ned says, and the atrium would require using additional materials. But Joe was intrigued, and after Anshen left, says Ned, "My father and I stood looking at all these scribbles."

August Strotz, who joined Anshen + Allen in 1956, remembers the atrium's birth a little differently. It was an architect-only session in the studio that included Anshen, Claude Oakland, and Strotz. They were kicking around ideas, as they always did, so it's hard to know exactly how the 'hole in the house' idea evolved, he says. "We would discuss design for hours and hours and hours," he recalls. "Then the two of us (Oakland and Strotz) would go sit down and draw this stuff." By the end of the session, he says, they had an outdoor room that was "surrounded by building and open to the sky." Strotz, along with Ned Eichler, credits Anshen with its invention. "Bob Anshen was the driving force in that outfit," Strotz says. "He was the designer and he was the idea giver."

Stephen Allen, Anshen's partner, told his origin story in a 1979 interview with Stanford graduate student JoAnne Wetzel: "The atrium house was done four or five years into the building of the Eichlers. Where did the concept originate? Bob and I both studied Latin. Perhaps that had something to do with the label. Of course, we both studied Roman architecture; that was the word the Romans applied. We'd also seen plans of Pompeii. And it was also affected by Eichler's purely economic view. With the atrium house, the secondary rooms had the privacy of opening onto the atrium."

In any case, say architects who worked at Anshen + Allen at the time, the design process was collaborative. "Bob was the conductor, like the guy with the baton. But the music was done in the background," Strotz says, meaning by "background" the draftsmen and designer Claude Oakland, who supervised them. "We were developing the ideas that Bob sprouted like the spring. He was a terrific designer."

Kinji Imada, who was later Oakland's architectural partner, also emphasizes the collaborative nature of design. "It was Claude's job to take Bob's ideas, redesign or refine them, and produce working drawings. It would be hard, if not impossible, to separate design and execution into working drawings - one is always designing as one works on working drawings."

"The way architects used to work in those days," says August Rath, who worked under Oakland at Anshen + Allen from 1957 to 1960, "Bob would say, 'Let's get all the ideas that we can. Let's get all the ideas out there.' So we would bust our buns coming up with everything we could think of." Anshen would contribute ideas of his own. "He was a great one with coming up with ideas that were oddball," Rath says. "Bob loved to go for something far out...This was not a closed show where Bob would walk around and say, 'Here's the plan. Let's draw it up.'"

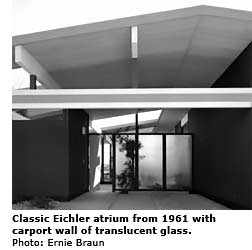

One goal of the E-11, an Anshen + Allen plan from 1957-58, which Munson says was the first real atrium model, was to provide light without adding windows that would reduce privacy. "In those days we had mahogany walls," she says, "so rooms were already dark. It was like the black hole of Calcutta in rooms that didn't have two windows." Other goals were to provide additional outdoor living, improve circulation, and add drama, says Rath, who did early drawings for the E-11. "It was part of the bigger picture of the house," he says. Eichlers are focused on backyard living, with the front of the house saved for cars and bedrooms. "You're living out of the back," he says. "How do you get to the back in an attractive way?"

The answer, he says: "Enter through an almost windowless front facade into a bright sky-lit garden area, and make a most enjoyable short journey to the floor-to-ceiling glass wall and the bright and open living area, which in turn opens to the rear garden beyond through a similar floor-to-ceiling glass wall. The net effect being that there is little or nothing between you and the beautiful garden you're in, and the garden in the rear. Now that's living!"

The atrium also provided usable space for gardening and entertaining, Munson says. Strotz says its contributions go even deeper. "The atrium in my opinion had a tremendous influence on the family life," he says. "The family felt much more like a nucleus within. It gave the family a closeness which the normal house doesn't have."