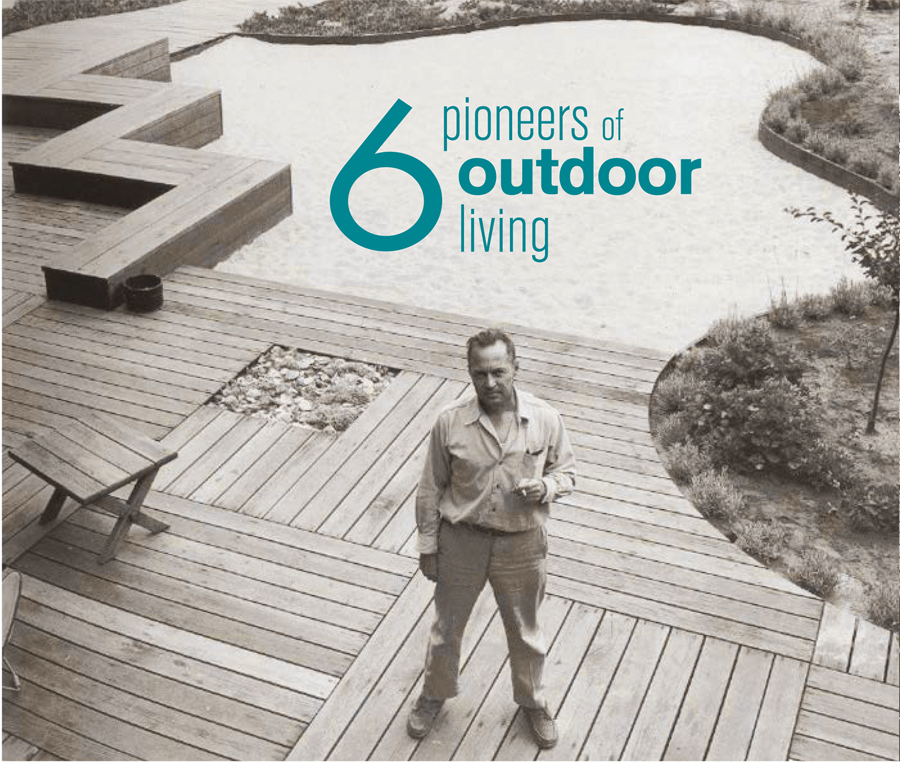

Pioneers of Outdoor Living

|

|

|

During the not-for-everyone dark days of the Depression, folks in need of a garden in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights or Hillsborough knew who to call.

Thomas Dolliver Church—known as ‘Tommy’ to some, ‘Dolliver’ to others—with his quick wit, unpretentious manner, and unerring eye for beauty, could produce a garden that was “absolutely Versailles,” in the words of one friend—even on a tight urban lot.

Folks in high society loved Tommy Church, and he loved them.

Odd thing to say, perhaps, about a revolutionary.

Still, in the late 1930s, Church helped give birth to the ‘California School’ of modern landscape architecture—and to modern landscape architecture itself.

Versailles? Bye bye.

Until Church and a small coterie of fellow modernists entered the field, landscape design in the main was either formal French, arranged with clipped hedges along a central axis, or naturalistic English, evoking an oh-so-romantic bosky dell.

The modernists didn’t go for either style, seeing both as irrelevant for modern man.

What was needed, the Bay Area-raised, Harvard-bred Garrett Eckbo argued, were landscape designs based on scientific analysis of the site and the needs of the client.

|

|

|

Rather than designing formal gardens for wealthy clients to look at or pursue their horticultural art, this new breed of landscape architects began designing gardens to be used as living space by ordinary people while serving, in Eckbo’s words, as “homes of delight, of gayety, of fantasy, of illusion, of imagination, of adventure.”

Landscape architects designing usable outdoor areas for ordinary people represented a major shift in the profession. It was good business, too, Eckbo noted.

“Such a concept of the garden increased the audience, and the possible clientele if you wish,” Eckbo wrote. “In our climate, people using outdoor space must outnumber [serious] gardeners by several times.”

Landscape architect Doug Baylis, who got his start working for Church, inveighed against the older generation of landscape designers, whom he called “the fuddy-duddies.”

Baylis “felt that classic landscape architecture was stuffy, that it related to ‘what did it look like,’ rather than ‘what did it give,’” his widow, Maggie Baylis, told an oral historian in 1977.

Baylis’s goal, she said, was to “help people live better,” a goal he shared with the entire modern school, which produced “outdoor living rooms” and tried to integrate indoor and outdoor living.

The residential gardens (including many for Eichler subdivisions and individual Eichler homes), campuses, parks, and civic and highway projects designed by Church, Eckbo, Baylis, Lawrence Halprin, and Theodore Osmundson came to define the modern California school of landscape architecture.