Pioneers of Outdoor Living - Page 7

|

|

|

|

|

|

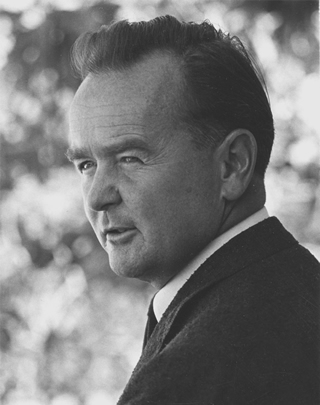

6. Douglas Baylis

Of all the young landscape designers who worked with Tommy Church in the 1940s, Doug Baylis (1915-1971) may have been most like him. Both were “soft,” Doug’s wife, Maggie Baylis, has said, men who could enjoy time together without speaking much.

Both preferred to design in a “loose” manner by drawing informal sketches, she said. Neither liked the more formal practice of drafting their designs—though when Church hired Baylis, drafting was his chief assignment.

Most importantly, both believed that the goal of landscape architecture was to “help people live better,” she said. It was a goal Baylis never dropped.

Baylis designed landscapes for universities, mortuaries and churches, wineries and office complexes, Eichler’s San Mateo Highlands neighborhood, and Civic Center Plaza and Washington Square in San Francisco.

But he made his biggest mark on small residential gardens, in large part thanks to dozens of articles he turned out for several popular magazines, most illustrated by his wife, a graphic artist.

Among Baylis’s more thought-provoking landscapes was the one he designed for Eichler’s all-steel X-100 house in San Mateo, in 1956, where planted areas both outside the house and inside harmonized with the repeating circular pattern of the swimming pool and aggregate deck and flooring.

Baylis, who opened his office in 1945, believed that anyone, no matter how poor a gardener, no matter how small the space, could and should achieve “luxury living on a budget lot,” the title of one of his articles.

He pushed for maintenance-free plantings (avoid long hedges that need trimming), a “play area you can see from kitchen window, paved for all weather use,” trellises for rain-free seating areas, and screens and louvers and translucent glass rather than solid wood fences.

“Want to avoid the appearance of living on a postage stamp?” Baylis asked readers in 1950. “This 50-foot lot gets its big look by using planting to create a sense of mystery beyond what one can see. The lawn curves out of sight, and its end is screened from the house by a mass of shrubbery. Imagination does the rest.”

“You’ll live better,” he wrote, “if you have a good lot plan.”

Photos: Ernest Braun, Philip Fein, Rondal Partridge (©2014 Rondal Partridge Archives); and courtesy JC Miller Archive, Environmental Design Archives - University of California Berkeley (the collections of Thomas D. Church, Garrett Eckbo, Douglas and Maggie Baylis, and Philip Fein), Lorraine Osmundson