Playing With Space - Page 3

Kappe's Sultan House, a series of interlocking levels with outdoor decks, uphill and downhill gardens, and interior bridges, has been turned into a private museum of modern art by owner Dallas Price-Van Breda, who considers the home itself a work of art. "Every time of day this house is so exciting," she says. "Morning, noon, and night, in the rain and in the sun."

Though Kappe is known for working in wood, that's due more to client wishes than his own predilection, he says. "I enjoy construction processes or systems -- wood, concrete block, steel, that's all fine with me," Kappe says.

Consider the Bruce Shapiro house, a set of interlocking concrete cubes that step up a hillside. It's got the standard Kappe strength -- and odd-shaped windows -- but a simplicity and coolness not seen in his other houses. "I got the house I wanted," Shapiro says.

Some of Kappe's later, concrete houses also drop his intersecting-planes look for a curvilinear, sculptural play of volumes.

Throughout his career, Kappe has built green -- or tried to. Kappe pushed for passive solar heating, solar hot water, and passive cooling based on thermal mass and convection. But all too often, he says, his clients nixed his proposed energy-savings measures in order to save on construction costs instead.

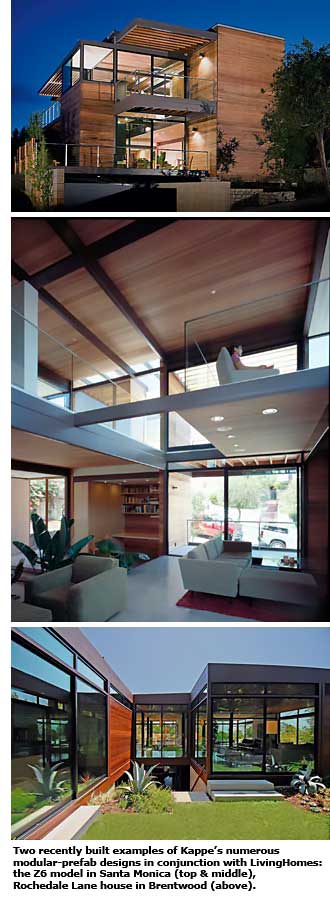

Still, Kappe says, his use of proper orientation, energy-efficient glass, and thermal mass-produced buildings beat most of the competition. And his first prefab house, for the Los Angeles firm LivingHomes in 2004, was the first LEED certified platinum house in the country. Goals for his future LivingHomes, Kappe has said, "are zero energy, zero water, zero carbon, and zero emissions."

High hopes, indeed. But Kappe has always been optimistic, nowhere more so than in his plans for Southern California, mapped out through studies he led during the 1960s and 1970s, first pro bono as a member of advocacy and planning bodies, then with a partnership he formed with several colleagues.

Their plans called for preserving hillsides by concentrating development in the valleys. "You could get the same amount of houses while leaving 60 to 70 percent of the land for park," Kappe says.

"The goal was to create better cities," Kappe says. "I was probably over-ambitious. As head of the AIA's urban design committee, I had a design for the whole city of Los Angeles."

Los Angeles could be transformed by encouraging telecommuting and tele-shopping (decades before the Internet made it possible), with goods delivered not by truck but through underground tubes. Instead of cars, people would get around hands-free in tiny, computer-controlled vehicles.

The city would be divided into four-square-mile neighborhood grids, with businesses and cultural centers clustered near freeways. Neighborhood streets, freed of traffic, would become greenbelts.

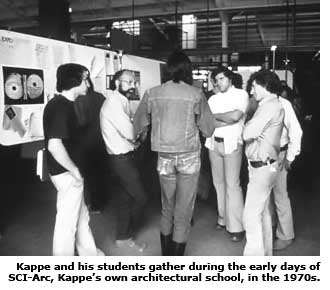

Kappe also played a role in the wider world as an educator, teaching architecture at the University of Southern California, then founding the architecture department at Cal Poly Pomona, before splitting off and founding his own school, SCI-Arc (Southern California Institute of Architecture), after a dispute with the dean at Cal Poly cost him his job.

The dispute grew heated, Shelly remembers. Student protesters wore T-shirts emblazoned with Kappe's face. This was, after all, the start of the 1970s, a rebellious time. "Ray was fearless, actually," she says. "Otherwise, to start a school of architecture -- people said, 'What!?'"

Kappe and five members of the Pomona faculty, including Thom Mayne, rented a building, and students built drafting tables from sawhorses. Shelly taught architectural history. "How would a curriculum evolve," Kappe mused, "if you didn't have it prescribed?"

Mayne, today an internationally known architect, credits Kappe for bringing in faculty with strong personalities and radically different ideas than his own. "What's really interesting about Ray is his incredible tolerance for really radically different views. We used to have debates that were more than lively," Mayne says. "They were emotionally filled and unusually open. Ray and I used to have fights. There was screaming and yelling. They were strong. But the next morning we would hug, and go at it again."

Surprisingly, perhaps, SCI-Arc succeeded and remains a respected school today. Kappe attributes its initial success in part to experience he gained working in his parents' store. "I knew how to keep books -- which most architects don't."