Roaring Back - Page 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"I actually coined the term 'mid-century modern,'" Greenberg recalls. "It wasn't in use before my book came out."

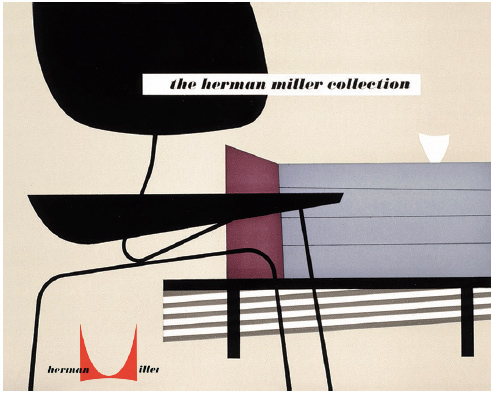

It's notable that Greenberg's book focused, not on homes or even architecture, but on furnishings and décor. Chairs by Charles and Ray Eames, ceramics by Eva Zeisel, and lamps by George Nelson that at one time could be had for a song, as they might say in the '50s, were soon valuable collectables.

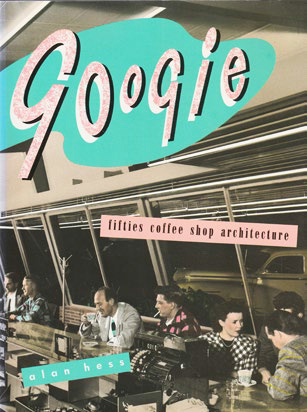

Another early proponent of the revival was Alan Hess. His first book, Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, from 1985, focused largely on the neon-bedecked, glass-and-aluminum roadside attractions known as coffee shops.

"My book really focused a lot of people's attention. 'There is something called mid-century modern and we like it.'"

Hess did as much to popularize 'Googie' as Greenberg did to popularize 'mid-century modern.'

"There was very little interest in mid-century modern," Hess recalls of the late 1980s. Still, Hess sensed a rising interest. "I was kind of terrified somebody else was going to write about Googie before I wrote my book," he says. In fact, that same year another book appeared celebrating the style: Fifties Style: Then and Now by Richard Horn.

What motivated Hess to produce 'Googie' was the demolition of Ship's coffee shop in Westwood, California.

The demolition "sparked an interest in the press and among the general population that was interested in design. Suddenly people realized: we're losing this and it's valuable. People took it for granted before. Now they realized it's disappearing."

The loss of Ship's led to the creation of a modernism committee that was part of the broader historic preservation group the Los Angeles Conservancy.

Interest grew in mid-century modern design throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, both in California and elsewhere. The movement became international in 1988 when architects in Holland founded Docomomo International, a modernism preservation group that now has local groups worldwide.

In Los Angeles, the Museum of Contemporary Art brought new attention to mid-century modern houses with a trend-setting exhibit in 1989, 'Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses.'

The first publication during the revival to focus on mid-century modern design was The Echoes Report, which began in 1992 as a slim, black-and-white magazine. It ended its run a decade later as the slick, color, squareback magazine Echoes, with a focus entirely on mid-century modern.

The magazine, which featured modern homes, in-depth features on designers, and more, played an important role in popularizing the style among collectors—and played a role too in two important transitions.

Like many dealers who would soon be focusing on art and objects from the 1950s and '60s, Echoes' primary focus originally was on the early, 1920s-'30s style of Art Deco. Its move to modernism reflected a shift in reader and collector interest.

And, by including articles on homes, Echoes also helped the mid-century revival movement shift focus from how people decorate their homes to how they live in them as well.

Suzanne Cheverie-Pugh, former Echoes editor and today a garden designer, saw the growth of interest in mid-century modern design as dealers and buyers came to appreciate its "utilitarian and classic design," she says.