Sacred Art - Page 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

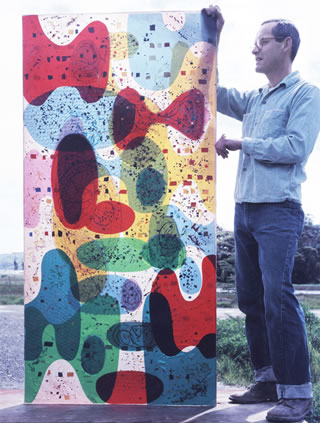

Rice was also finding success as a fine artist as well—winning a one-man show of paintings and mosaics at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor in 1963. “Rice’s artistic concept is uniquely his own,” critic Dean Wallace of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote after viewing “squat figures and glittering totems.”

“Here, naiveté itself becomes a kind of sophistication.”

Still, life was never easy. Rice, his wife Miriam, and daughters Mira, Rachel, and Felicia shared a houseboat that Rice hauled onto the shore of Corte Madera Creek, just off increasingly busy Highway 101 in Marin County, before the road became a super-highway.

Rice worked in a small studio he’d built near the house, often bringing in friends and fellow artists as assistants.

“It was kind of marginal,” Tepper said of their life in Corte Madera. “I think Ray felt pressured by that.”

Besides making art, Rice taught art—to prisoners in San Quentin from 1951 to 1953, then at the College of Marin from 1953 to 1970.

In the mid 1960s Rice turned his back on public art and on gallery shows—save for a community gallery now and then—and became an avant-garde filmmaker.

Rice moved, moreover, from the Bay Area, with its active art scene, to the hamlet of Mendocino, years before it won fame as a historic town and tourist mecca. To a large degree he dropped out of sight—which is where he remains today.

His work was not included in the recent Pacific Standard Time exhibits of mid-century art and design. His art cannot be found in major museums. Much of it remains in private hands—often that of his family. His films are in the collection of the University of California, Santa Cruz, but are not commercially available.

Rice’s retreat from commercial art production was in character. “He spoke disparagingly of the art market,” his son-in-law, Jim Schoonover, says. “I’m sure he was not going to put his work under his arm and go out with it.”

Mosaics, which came to define his art, Rice regarded largely as commercial work, not fine art, Tepper said, adding, however, “Whenever he got a project, he did it with 110 percent of effort and creativity.”

Perhaps Rice came to conclude that working in architectural settings no longer allowed him to make “a personal statement.” Or perhaps it was making a statement that ran counter to his feelings.